Why bond funds may be riskier than they seem

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Would a rose by any other name smell as sweet? It is a question many bond investors should be asking themselves and the managers of their money.

A bombshell paper that has been gradually wending its way through the peer-reviewed academic publishing process has now finally appeared in the latest edition of the venerable Journal of Finance, and deserves a wide airing.

Sifting through the individual reported investments of individual bond funds, Huaizhi Chen, Lauren Cohen and Umit Gurun found that almost a third of supposedly safe US bond funds are actually riskier than their classification would imply. The fitting title of the paper is: “Don’t Take Their Word For It”.

Damningly, the three researchers say it appears to be a deliberate ploy to game the rating system of Morningstar, the mutual fund industry’s dominant research house. “This misreporting has been not only persistent and widespread, but also appears to be strategic,” the paper argues.

Let us break this down. Most bond funds focus on a specific corner of the fixed income markets, say, corporate or government bonds, highly rated “investment grade” debt or securities rated below that, and often a certain maturity of debt. Morningstar then assigns them stars according to how well they do compared with other funds in their category.

But in reality, many bond funds classified as relatively safe have actually loaded up on riskier debt to juice their returns relative to their peers and the benchmark, the paper argues. That means they get a shinier star rating from Morningstar, which in turn leads to burgeoning inflows from investors that simply follow its influential rating system. When classified appropriately, many fund managers go from looking like proverbial Masters of the Universe to more like “mediocre performers”, the paper notes.

The report focuses on the discrepancy between a bond fund’s actual holdings and its Morningstar classification, and primarily castigates the former for seemingly deliberately misreporting and the latter for believing them.

Morningstar argues that the paper wrongly assumes that all non-rated debt must be of low quality, and maybe confuses its investment style and classification systems with the latter used to assign ratings. When the research house tried to recreate the study they found no meaningful relationship between supposedly “misclassified” funds and Morningstar ratings.

However, whatever the relative merits of the arguments over this particular paper, this is probably a far wider, more pernicious issue than many realise.

As AQR Capital Management showed in a 2018 paper titled The Illusion of Active Fixed Income Alpha, the phenomenon of bond funds flattering their results by loading up on riskier debt is a widespread one. In fact, this simple, systematic tilt towards lower-rated corporate debt explains why bond funds on average do a far better job of beating their indices than equity funds, AQR argued.

The quantitative investment group also looked for signs of reasonably consistent investment skill within different bond fund categories. “The evidence is fairly bleak: we see little evidence of persistent manager skill,” the paper concluded.

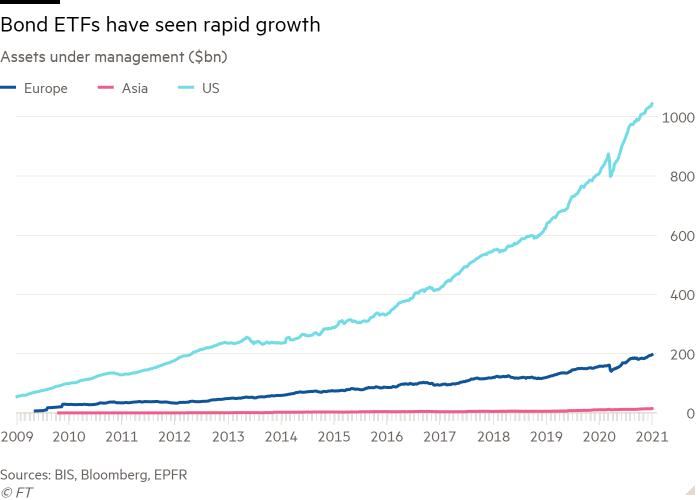

This is one of the reasons why passive investing is blossoming in bond markets. Just over the past five years, passive bond funds have taken in almost $850bn, even more than the far larger universe of active bond funds, according to EPFR. For many traditional investors, this is a travesty. They argue passive bond funds are at best dumb, given the fixed income market’s lucrative inefficiencies, and bond ETFs are downright dangerous. But investors are clearly voting with their money.

It is true that one could argue that overweighting corporate bonds, and especially lower-rated ones, is a natural and indeed clever decision by active managers that are paid to deliver greater returns — especially at a time when high-grade government bond markets yield close to or even below zero.

But the reality is that this transforms the nature of a bond fund. More risky, volatile junk bonds mean that they move more in tandem with the equity market. That is fine if it is transparently sold as a racier vehicle, but can be a nasty surprise for many investors that buy bond funds as a counterweight in their portfolios.

“When the tide went out during the initial Covid shock, many managers weren’t fully dressed,” says Mike Gitlin, head of fixed income at Capital Group. One of the roles played by fixed income managers, he observes, should be to ensure that you don’t “drive clients off the cliff when they need you most.”’

Twitter: @robinwigg

Email: robin.wigglesworth@ft.com

Comments