One of my earliest memories, perhaps the earliest of all, goes back to when I was about four years old, in 1946, living in the Bronx borough of New York City. I awoke to a searing headache and fiery fever, aching all over. I remember a tube being inserted into my privates, to help withdraw urine. I awoke again, I don’t know how much later, hours or days, in a hospital ward. In the bed next to me was a man engaged with a terrifying contraption I now know was an iron lung, to help him breathe.

I could breathe OK, and the terrible fever and headaches had subsided. But I couldn’t move my legs.

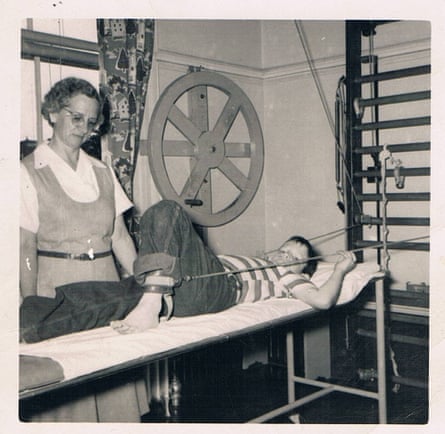

My disease, I soon learned, was called infantile paralysis, poliomyelitis, or just polio. I had a relatively mild version. Within two or three weeks, when the acute stage ended, I was taken across the Hudson River to a rehabilitation hospital in a place called Haverstraw, New York. Over a period of months there, helped by a determined staff, I gradually regained some strength in my legs. I could walk but not yet run. Still, I could go home to our apartment in the Bronx, reconnect with my brother and parents, and start kindergarten, on time, with my age mates.

Like much of America, we moved to the suburbs, to Connecticut and then to New Jersey. But summer after summer, fear of the virus followed us, particularly for my mother. Her brother as a young man had contracted a version of the disease that left him in a wheelchair for the remaining decades of his life. She lived in continuing terror that one or both of her younger sons would be afflicted, perhaps more seriously than her eldest.

The emergence of effective vaccines, starting in 1954, miraculously released such fears.

That left me as the lone member of our family with a continuing connection with polio. For me, having been spared the more serious consequences of partial or total paralysis, the lifelong after-effects of polio have been occasionally quite painful but mostly an annoyance.

Up to now. The advent of new viral agents of disease, most particularly the coronavirus, and my own experience with polio’s manifestations in later life, have made me more sensitive to the risks the polio virus may hold in the future. Unless we humans can commit to greater discipline in eradicating the virus altogether, polio conceivably might have a new day in the sun. More broadly, other viruses may prove harder to control, because vaccines, by far the most effective tool against them, work best when everyone is treated.

Just a few years ago, things were looking a lot more encouraging.

David M Oshinsky’s 2005 book, Polio, An American Story, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for history, dramatically lays out how individual scientists, universities, drug companies, private charities, and government at all levels – working separately and together in the 1940s and 1950s – proved the safety and effectiveness of two competing anti-polio vaccines. The vaccines then became part of the routine for countless children in the United States and most other economically developed countries, largely eliminating new polio infections there.

Next efforts turned to less-developed countries in Asia, Africa, and elsewhere.

In 1988, the World Health Organization, Rotary International, and what is now the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched their Global Polio Eradication program, aimed at eliminating polio, the way predecessor efforts had done with smallpox. At the time, 350,000 children in 125 countries were infected with the disease, according to Rosemary Rochford, a virologist and professor of immunology and microbiology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, writing in The Conversation. By 2021, the number was down to six cases around the world, she wrote.

Meanwhile, the success with polio elimination had helped pave the way in the United States for development and introduction of vaccines for measles in 1963, then for such other diseases as mumps and rubella. The combined “MMR” vaccines became standard for babies in the United States.

Then trouble emerged. Some reports, though definitively discredited, gave rise to the belief in a link between vaccination and autism. When the coronavirus struck, researchers and drug companies rapidly produced safe and effective vaccines to repel several versions of the mutating Covid virus. But the other side of the vaccine-versus-virus equation – getting everyone vaccinated – was no longer so readily achieved.

Whether for politics, religion, fear of side effects, or a prioritization of individualism, some people no longer embraced the collaborative spirit that made other massive vaccination drives so successful.

The commitment to social good necessary to meet public health challenges became apparent not just in the coronavirus, but also in seemingly conquered diseases like polio. An unvaccinated adult in one of New York’s suburbs was diagnosed with the disease. Polio virus samples were detected in the city’s wastewater.

These are small signs so far. But these are my neighbors, my nearby neighborhoods. And we know that viruses mutate, and that they can cause long-term damage.

I empathize with people struggling with long Covid, because polio is a disease that can re-emerge with age. I was in my 60s when I first began to notice my leg muscles atrophying. For a time, exercise helped. But as I turned 80 this summer, my leg weakness has increased. I have trouble with slightly hilly sidewalks, for instance. My doctor is the same age. No polio. No trouble with hills.

As a species, we are slowly beginning to take actions in order to keep our physical world livable. We’re also learning how the tiniest organisms – insects, and yes viruses – adapt to our changing environment. Inventing vaccines may no longer be enough. We may well have to adapt our behavior to help the vaccines work.

The scratch and scar I got on my arm as a kid was enough to assure my age cohort didn’t have to worry about smallpox, so long as we all got the same scar. It is time to recognize that personal wellbeing depends on individual investment in the greater good.

Paul Steiger is the founder of ProPublica and the former managing editor of the Wall Street Journal. Dean Rotbart’s biography of him is scheduled for publication next year