Can a Million Chinese People Die and Nobody Know?

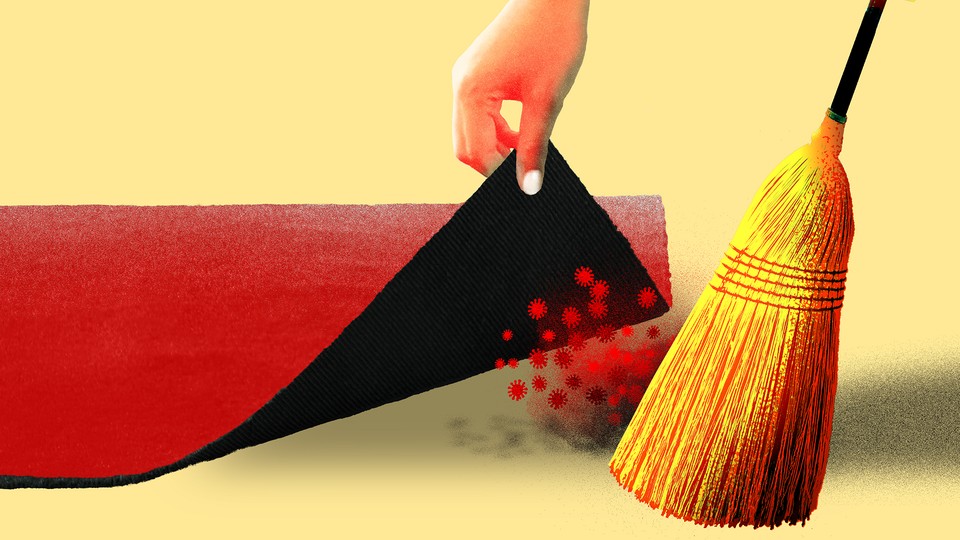

Official statistics on COVID can’t be trusted, because they serve Beijing’s political interests. Making the dead disappear is only part of it.

Can a million people vanish from the planet without the world knowing? It seems impossible in this age of instant digital communications, ubiquitous smartphones, and global social-media platforms that anything of comparable consequence can go unnoticed and unrecorded—no matter how remote the country or how determined its rulers might be to hide the truth.

Yet that’s apparently what has happened in China over the past two and a half months. After the Chinese leader Xi Jinping removed his draconian restrictions to contain COVID-19 in December, the virus rampaged across the nation with explosive speed. According to one of the government’s top scientists, 80 percent of the populace has now been infected. But we don’t know the full impact of this surge. The Chinese government’s secrecy has managed to obscure what really happened during the country’s latest and worst COVID wave.

Independent experts, skeptical of Beijing’s official data on COVID deaths, have been forced to calculate their own estimates—which indicate much higher and more disturbing numbers than the government claims. These estimates range from about 1 million to 1.5 million deaths, suggesting that, in absolute terms, China may have suffered more fatalities from COVID in two months than the U.S. did in three years.

By any reckoning, a terrible tragedy unfolded in China in recent weeks. That we’re left guessing about its scale is important as well. If the Chinese leadership can hide a million dead, what else can it conceal from the world? Authoritarian states have a notorious history of shielding the sufferings they inflict from the eyes of the world. The number of Chinese people who perished in the famine caused by the Great Leap Forward (1958–60), Mao Zedong’s crash modernization program, is still a subject of debate. In the era of Stalin’s gulags and Nazi concentration camps, limited technology and limitless repression helped dictators screen their atrocities.

Today, information wants to be free, as the netizen slogan goes. In a time when everyone carries the equivalent of a TV camera in their pocket and when satellites whir over a world saturated with open-source data, a new tech-empowered army of civic-minded citizens and whistleblowers was supposed to keep a closer watch on the bad guys. With greater transparency would come greater freedom.

The controversy over China’s death count, however, shows how much control autocratic states still wield over information. As China rises, its leadership’s inherent secrecy is a problem for all of us. Decisions made in Beijing and events in China have ramifications for global economic growth, jobs, prices, the environment, the stock market, and global security. But all too often, the world has to rummage through scraps of anecdotal evidence, opaque official pronouncements, and glimpses provided by outsiders to guess at how Beijing chooses its policies, and at the effect they have on the country—and thus China’s impact on our lives.

The Chinese Communist Party likes it that way. All governments have their secrets, of course, and try to spin news cycles and narratives. But in open societies, the debates of congresses and election campaigns expose the policy-making process to public view. Journalists, activists, and regular citizens are always poking around, asking uncomfortable questions, and posting on Instagram and TikTok.

No authoritarian state could survive that scrutiny, and the Chinese Communist Party has erected an extensive security state to make sure it doesn’t face such examination. China’s party-controlled legislature—the National People’s Congress, which is due to meet in early March—is more a pep rally than a debating society. In the absence of a free press, no watchful estate of reporters exists to keep tabs on the powerful. The intrepid and inquisitive are usually silenced: The citizen-journalist Zhang Zhan, for instance, was sentenced to four years in prison for documenting the original COVID outbreak in Wuhan in 2020.

As powerful as China’s police state is, however, it does not control every source of information. During the recent wave of infections, satellite imagery revealed heightened activity at cremation centers. In addition, domestic footage of overwhelmed hospital wards found its way onto Chinese social media. But once detected, such glimpses are quickly removed by China’s platoons of censors.

Concealing inconvenient truths is an industrial enterprise for the Communist Party. The Tiananmen massacre of 1989, common knowledge to much of the world, has been scrubbed from the domestic record. More recently, the Chinese government has worked to hide its mass detentions and torture of China’s minority Uyghur community in the Xinjiang region.

Chinese authorities have been obfuscating on COVID-19 since the pandemic began. The World Health Organization’s investigation into the origins of the coronavirus has stalled because of China’s lack of cooperation, but the Chinese foreign ministry continues to deflect responsibility by regurgitating an old conspiracy theory that the virus originated in the United States. Now the government appears to be trying to erase the country’s entire COVID experience from national consciousness. The zero-COVID policy, which employed large-scale quarantines and business shutdowns to contain the virus, had been heralded by authorities as a “magic weapon” to protect the people. But since the restrictions were removed, the term zero COVID has vanished from official discourse.

Next to disappear is COVID itself. China’s equivalent agency to the CDC determined recently that a new cycle of mass infection is “unlikely to occur” in coming months.

The government has tried to bury the memory of the dead with as much dispatch as it ditched its lockdowns. When COVID began to spread rapidly in December, the initial death counts released by the health authorities were so unbelievable that even the party brass seemed to realize they lacked credibility. That led to a mid-January announcement that 60,000 people had perished in the latest wave, and, more recently, the official tally of deaths has risen to a touch more than 83,000. We can’t say with absolute certainty that the Chinese government’s data are false, but public-health experts and other specialists have looked askance at these figures. Yanzhong Huang, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations, called them a “vast undercount.”

One possibility is that China’s top leaders do not themselves know the real total. Contrary to the widely held image of China’s autocrats as a surveillance state’s all-knowing supervisors, the leadership in Beijing can, by the very nature of its rule, be left in the dark about what’s happening in the country.

“We think of China as a very high-capacity authoritarian regime, where the center is in control,” Jennifer Pan, a political scientist at Stanford University, told me. “The reality is that every authoritarian government that does not have free media faces a problem where they have trouble gathering reliable and accurate information.”

“Governance is delegated to local governments, and local governments have very strong incentives to keep bad news from being seen by the center,” she went on. “In order to be promoted, they have to show they are doing well.” In the case of COVID deaths, “we shouldn’t necessarily assume the central Chinese government has an accurate handle of what is going on.”

In the absence of reliable information, the Communist Party can conjure its own version of reality—and the leadership has embraced a narrative to fit the data it has, last week declaring that it had achieved a “major and decisive victory” over COVID and “effectively protected the people’s lives and health.” With this success, “China has created a miracle in human history.” A commentary published by the official news agency, Xinhua, added that the triumph was evidence of the party’s “governance capacity.”

Whether the Chinese people swallow this swill is another unknown. Without freedom of speech, the government also denies any true picture of public opinion that might open up the Communist Party to criticism. But the party has little choice but to promote this kind of narrative. Because its leaders present themselves as infallible, they can never admit to the full extent of the COVID catastrophe.

“Shocking the public presents a threat to the government,” Eric Harwit, an Asian-studies professor at the University of Hawaii at Manoa who studies Chinese social media, told me. The authorities “think it’s something the people can’t handle—they can’t handle the truth.”

Beyond that, the state and its supporters had previously promoted China’s comparatively low death count to claim that the country’s authoritarian system, which had rigidly imposed the zero-COVID policy, was superior to other forms of government, especially liberal democracy. Revealing the real death count would not only damage the party’s reputation at home but also embarrass its leadership abroad.

Yet the party’s penchant for misinformation comes with risks. Average Chinese citizens have more information at their fingertips than they’ve had in the past, thanks to smartphones and social media. As extensive and effective as the authorities’ censorship operation is, it can still be caught off guard by popular expression on social platforms, which allow individuals to connect with a broad network of people and sources. Over time, the gap between what the officials say and what the public sees could damage the party’s credibility.

The case of the missing million is a chilling reminder that the Communist Party can still make people disappear, and the world may never know. Beijing’s secrecy creates other, immediate problems. How can a government unwilling to reveal COVID deaths be trusted to share other vital information, such as China’s greenhouse-gas emissions, crucial to tackling global warming? Beijing’s resistance to cooperating with the international community in a search for answers about the origins of this pandemic does nothing to help world leaders prevent the next one. The fact that we barely understand how Xi and his team have made COVID-related decisions is an indication of how cloistered the party’s inner sanctum remains.

The chasm between what we know about China and what we need to know about China is much too large. The party will keep it that way.