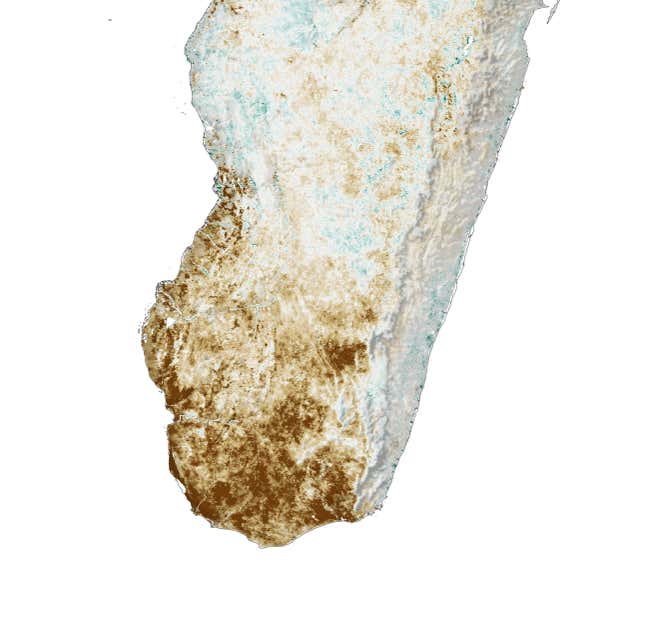

Madagascar is being hit by one of the modern world’s first climate change-induced famines—a disaster that underscores the profound unfairness of a planet heated up by carbon emissions.

The famine, caused by a devastating, four-year drought, is placing at least 30,000 people in the most extreme stage of food insecurity: a level five famine, as defined by the World Food Programme (WFP). At least 1.1 million are in some kind of severe food insecurity, the United Nations has said. “People have had to resort to desperate survival measures, such as eating locusts, raw red cactus fruits, or wild leaves,” Amer Daoudi, a senior director at WFP, told the UN earlier this year.

How climate change can cause a famine

Madagascar produces a little more than 0.01% of the world’s annual carbon dioxide emissions every year, according to data drawn from the Global Carbon Project. Cumulatively, between 1933 and 2019, the country produced less than 0.01% of all the carbon dioxide generated—the carbon dioxide that is now triggering severe alterations to global climate. One such effect of these alterations has been Madagascar’s drought, the worst in 40 years.

The drought, and therefore the famine, can be directly attributed to the effects of climate change, David Beasley the WFP’s executive director, has said. It has also compounded by unexpected sandstorms that have “buried fields, undermining any possibility of farming,” said Frances Kennedy, a WFP spokesperson, in an email to Quartz. More than 60% of the people in Madagascar’s south, she said, “are subsistence farmers who have lost their livelihoods as well as their only source of food to erratic weather.”

Scientists have been analyzing climate patterns for years now to predict these kinds of consequences for southern Africa. But that hasn’t necessarily made it easier to forestall such calamities. “Going by the statistics, over the past 20 years, there’s been a 500% increase in the number of countries exposed to multiple types of climate extremes,” Kennedy said. “We are seeing the effects of climate all over southern Africa.”

Angola is another example of a country witnessing food shortages as a result of climate change, Kennedy said. “Nearly seven million people have little food and thousands have become migrants fleeing into Namibia in search of food. Frequent cyclones forming in the Indian ocean and hitting the southeastern coast of the continent (Mozambique) are now becoming more frequent and impacting food security.” As with Madagascar, Angola and Mozambique have contributed minimally to global emissions.

In being able to trace the famine directly to climate change and not to conflict—the more familiar reason—Madagascar’s situation is “unprecedented,” Shelley Thakral, a WFP spokesperson, said to the BBC. “These people have done nothing to contribute to climate change,” Thakral said. “They don’t burn fossil fuels…and yet they are bearing the brunt of climate change.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech, and innovation in your inbox.