America’s Safety Net Is Failing Its Workers

Stories from a country that was wildly unprepared for a pandemic.

Chrissy Ormond De Swardt was having a cookout when she learned she’d lost her job. She and her husband, Bennie De Swardt, had spent the first week of March in Indian Wells, Calif., setting up for the BNP Paribas Open, a two-week tennis tournament expected to draw half a million spectators. Chrissy works in event production, overseeing players’ walk-out routines, award presentations, and other minutiae. Bennie, a camera operator and supervisor, makes sure the matches look good on TV.

On March 8, the night before the qualifying rounds were set to start, the couple invited some colleagues over to the house where they were staying for a barbecue. Bennie grilled salmon and steak as people debated whether Rafael Nadal or Novak Djokovic would beat the defending champion, Dominic Thiem. Chrissy was inside getting napkins when her phone buzzed with a text from a friend: “BNP IS CANCELED?! What does that mean for you and Bennie?!” Confused, Chrissy checked the event’s website. A banner appeared, announcing that because of confirmed cases of Covid-19 in Coachella Valley, the tournament wouldn’t be held. It was the first professional sports event to be canceled in the U.S.

“We were so naive about what would happen,” Chrissy recalls. “We thought we’d still be able to work.” At the time, there were only 550 confirmed cases in the U.S. There were no stay-at-home orders yet, no shuttered businesses. The couple assumed they’d just move on to their next job, a golf tournament. For years they’d traveled the world, helping produce everything from the World Cup to the Olympics. Like almost everyone they worked with, they were freelancers, with no paid vacation time, no sick leave, no employer-backed health insurance. Their only job security was that a sport was always in season somewhere.

Over the next 10 days, all their gigs through August were canceled. “It just kept coming and coming and coming, event after event,” Chrissy says. “It was brutal.” On the flight home to Chicago, the couple listed their monthly expenses on a cocktail napkin. Property taxes and utilities were non-negotiable, but they could cancel cable. The $1,000 monthly premium they paid for health insurance through the Affordable Care Act marketplace? A pandemic wasn’t the time to drop that. To keep some money coming in, Chrissy would fall back on her side job as a substitute teacher. “No sooner do we land in Chicago than I see that schools are shutting down, too,” she says. Freelancers didn’t yet qualify for unemployment. They were out of options and staring down six months with no income. They only had enough savings for two.

As Bennie and Chrissy tallied their finances, Andrea Lockhart was working out how to pay rent on her house in Taos, N.M. She’d lost her job as admissions director of a local school in December after a toxic-mold discovery closed the building indefinitely. As a single mother with three children under age 7, she’d taken the first two gigs, both part-time, that had come her way, selling women’s clothing at one store and Southwestern jewelry and gifts to tourists at another. The $15 an hour she made, plus $676 in food stamps each month, kept her afloat. Or not afloat, exactly—she also owed $1.5 million in medical bills from the birth of her youngest child, 2-year-old Abby, who’d arrived prematurely and spent a month in a neonatal intensive care unit. Lockhart let those bills go to collections. “Things were tight. It was paycheck to paycheck, but I’m superdiligent about my budget,” she says.

On March 15, both stores closed. Lockhart could have filed for unemployment, but the owner of the store she worked at most discouraged her from doing so. “She said if I did that it would financially ruin her,” Lockhart says. “I don’t know how unemployment works, so I didn’t.” With no money coming in, she stopped paying bills and cut back on groceries. “The little ones used to go through about a gallon of milk a day. Now they’re only getting one cup at naptime and some at dinner, and that’s it,” she says. “There’s a lot of crying.”

In the almost three months since isolation measures were put in place to slow the spread of the coronavirus in the U.S., the economy has all but collapsed, and the damage has been swift. A quarter of small businesses and two-fifths of restaurants have closed at least temporarily. By June an estimated 1 in 4 American workers was out of a job; 40 million people have filed for unemployment so far, more than the population of California.

And while the virus has devastated almost every economy it’s touched, Americans entered the crisis in an especially vulnerable position. The world’s wealthiest country, home to more than two-fifths of all millionaires, also has one of the highest poverty rates and widest wealth gaps of any developed nation. Despite the booming stock market and robust job growth of recent years, more than 38 million Americans live in poverty. In January the Federal Reserve reported that almost 40% of U.S. adults would struggle to come up with $400 in an emergency.

Things were especially bleak for minority groups when the shutdown began. Black Americans have less than 3% of the country’s wealth despite making up at least 13% of the population. They’re more likely to lack access to health care and nutrition, which left them more exposed to the virus. And the jobs they and Latino workers tend to hold were more susceptible to layoffs than ones held by white workers; these jobs are also disproportionately consumer-facing, putting minority workers at greater risk if the country reopens too quickly and infections spike again.

Even the country’s middle class, presumably the bedrock of the economy, was in a weakened position. According to the Fed, middle-class families have the smallest share of U.S. wealth—just 25%—since tracking of this measure began in 1989. (The top 20% of income earners, meanwhile, have amassed 73%.) Adjusted for inflation, median household income is about the same as it was 20 years ago, even as the costs of housing, health care, child care, and college tuition have skyrocketed. “In the 1980s, middle-class families used to have enough financial reserves to support about two or three months of normal consumption,” says Edward Wolff, a New York University economist who studies wealth disparity. “Now it’s about one week.”

The U.S. also has a relatively weak social safety net, the product of decades of political inertia, a widespread belief that government is the cause of society’s problems rather than a vehicle to solve them, and politicians who’ve railed against expanded benefits using racist stereotypes of minorities seeking handouts. (Think Ronald Reagan’s invocation of “welfare queens.”) Some European countries, by contrast, were able to rely on existing social programs to ease the pain of their shutdowns—for example, by subsidizing businesses so workers could keep receiving a paycheck while sheltering at home. In the U.S., employers rapidly shed tens of millions of people from payrolls, forcing them to apply for financial assistance with no guarantee of regaining their jobs. In May the Fed reported that almost 40% of people who earned $40,000 or less a year—the group least likely to have health insurance or enough savings to get through the crisis—had been laid off or furloughed. “This is not something you can address by just fixing the markets or pushing a big influx of money,” says Sandra Black, a Columbia University economist. “There is something fundamental going on here. The U.S. is really behind.”

The virus has posed an essential question for Americans: How will we take care of each other, now and in the future? The early stages of the crisis saw broad, bipartisan support for federal intervention, including the $2.2 trillion provided by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (Cares) Act. It was a staggering amount of money, equivalent to about a tenth of the U.S.’s annual gross domestic product, but much of the aid was designed to be temporary, even though the needs it addressed were new only in their scale. Because they’d ignored these problems in healthier times, legislators were forced to create entire programs on the fly. They’d essentially watched the country fall out of an airplane and only later decided to look for a parachute.

The result was a shifting, friction-laden response that sometimes created more problems than it solved. As it unfolded, I talked to more than two dozen workers and small-business owners about how they were managing. Only two of them—a cybersecurity expert in North Carolina who was confident he could find another job and a retired General Motors Co. engineer who owned a rental property in Detroit—thought they’d emerge from the pandemic relatively unscathed. Everyone else spoke of overriding feelings of confusion and uncertainty. Nobody knew what was going on. And so I tracked the chaos.

On March 16, Bob Bernstein called his managers in for an emergency meeting. For 27 years he’d owned Bongo Java, a collection of six coffee shops and casual restaurants in Nashville. Bernstein’s sweet potato biscuits and pork belly scrambles had inspired a devoted following, and he’d built robust wholesale bakery and coffee-bean businesses, too. His 150 employees could get health insurance, and his managers got as much as three weeks of paid vacation every year. Aside from one outlet that was destroyed by a tornado earlier this year, he’d never closed a store, not even after the 2007-08 financial crisis. “People still drink coffee in a recession,” he says.

The day Bernstein called the meeting, though, there were 4,500 confirmed cases of coronavirus in the U.S., 25 of them in Nashville. The city was still a week away from closing its shops and restaurants, but he was concerned for his workers’ safety. “Do we try to employ people, or do we shut down to not spread a virus?” he recalls thinking.

At first his managers agreed to stay open. Then San Francisco announced a shelter-in-place order, and the White House recommended that people stay home for 15 days. “That was it,” Bernstein says. “We had to close.” Bongo Java’s chefs cooked all the perishable food and packed it up for their co-workers.

Bernstein wanted to keep everyone on his payroll so they wouldn’t lose their health insurance, but his policy stipulated that covered employees had to work at least 30 hours a week. He contacted his insurer to see if the rule would be suspended, then tried calculating Bongo Java’s share of the premiums. He soon realized that the company couldn’t afford to cover everyone even if his insurer waived the 30-hour rule, and that he definitely couldn’t keep paying their salaries. He had to lay off all but four of his employees. “I couldn’t even do it in person,” Bernstein says. “I would have. But we weren’t supposed to meet in large groups.” His managers spoke with staff who were in that day. Everyone else got an email. “I told them they have to go on this Cobra thing, which I don’t totally understand,” he says.

He was referring to the federal program that allows the newly unemployed to temporarily extend their health coverage by paying the full premium, plus a 2% administrative charge. Only one of the many workers I spoke to considered Cobra a viable option. The rest said it was too expensive. In the early days of the pandemic, several House Democrats proposed subsidizing Cobra premiums, as Congress did in 2009, but the proposal didn’t make it through the House.

The government did little to address that millions of Americans were losing their health insurance. A study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine on April 7, just two weeks after the law passed, put the number of Americans who’d lost employer-provided coverage at 7 million. The for-profit hospital system Health Management Associates estimated that the number could top 35 million by the time the pandemic has run its course.

Even a reduction in hours was enough to make people lose coverage. Jessica Hodge, a behavior specialist who works with autistic children in Virginia, had this happen to her. She’s pregnant, and when she told her employer she was uncomfortable making house calls without protective gear (the company said it couldn’t provide any), she was given the choice of quitting or dropping to part time and losing her insurance. She chose the latter. “It’s scary,” Hodge says. “Who wants to lose their insurance when they’re pregnant?”

Those who lost their jobs didn’t find the exchanges created under the Affordable Care Act to be much help, either. “The plans I found came out to about $1,000 a month. Who has an extra $1,000 a month right now?” asks Marie AuBuchon, who was laid off from her job hauling sand for a Texas fracking company. AuBuchon has lupus and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, both of which cause severe joint pain. “I’m just taking Tylenol and trying to muddle through.”

As Bernstein was closing down Bongo Java, Briggs Anderson was having a different problem in Montana. Three of his employees had gotten sick, two of them with symptoms consistent with Covid-19. Anderson owns seven Jiffy Lubes that collectively employ about 48 people. He wouldn’t have to close up—automotive repair shops had been declared essential businesses—but people weren’t bringing in their car unless they absolutely had to. In the first week of Montana’s shutdown, his sales dropped 30%.

Anderson isn’t sure if his workers actually had the virus. “No one’s getting tested out here,” he says. He offers health insurance, but given that his employees make $25,000 to $40,000 a year and premiums are expensive, only about a fifth of them opt for coverage. The rest either qualify for Medicaid or go without. As a result, just one of Anderson’s sick employees sought medical attention, a telehealth visit with a nurse who told him he couldn’t get tested but to go ahead and self-quarantine for two weeks.

Twelve U.S. states have paid sick leave laws, but Montana isn’t one of them. Anderson knew what a burden it would be for his workers to stay home. “I told them I’d make sure they were OK,” he says. He wound up paying about $4,000 so they could take 25 days off, combined. “How many people can I realistically do that for?” he asks. “The lack of testing exacerbates the problem. You stay home for two weeks, and I pay you for two weeks, but I don’t even know if you have it? That’s an expensive way to do things. There has to be a better way. Workers can’t just rely on getting paid out of the goodness of my heart.”

The goodness-of-an-owner’s-heart approach doesn’t scale well, either. For years the Cheesecake Factory gave its restaurant workers the option to have money set aside from their paycheck for a “HELP Fund” that would provide as much as $1,000 to cover “shelter, food, utilities and/or childcare” in the event of an emergency. On March 19 the company furloughed 41,000 workers, which left it facing tens of millions of dollars in potential payouts. The same day the chain sent an email telling employees that “loss of income due to the pandemic does not meet HELP Fund grant requirements.” Instead it was establishing a $2.5 million Covid-19 Assistance Fund, which would pay up to $500 to those “most impacted.”

So many people applied for the assistance fund that the company had to “temporarily pause” the application process after four days. It was briefly restarted, then shut down again. “I’d been paying into the HELP Fund for seven years. I couldn’t even tell you how much I’ve contributed,” says Kade Stone, a server at a Cheesecake Factory outside Dallas. “What was the point?” A spokesperson for the company said it had distributed almost $2.5 million but otherwise declined to comment.

Other countries have been managing to keep people at home without mass unemployment and all the problems that come with it. Denmark, for example, poured the equivalent of an eighth of its GDP into a program that guarantees 75% of workers’ salaries for at least 13 weeks. Germany relied on a similar, century-old program that pays the majority of salaries when there’s a temporary shortage of work. When the pandemic hit, the program was already so well-funded that officials didn’t need to do much beyond relaxing the rules for applying.

One advantage of this approach is that when the economy restarts, workers and employers don’t have to scramble to find or fill new jobs. It also reduces paperwork; in March, Germany had to process only the 470,000 applications filed by companies, rather than 9 million unemployment claims from their employees. That helped money get out faster. “I haven’t had to do anything,” says Lilia Prelević, who manages a clothing store in Denmark. “I didn’t miss a paycheck. In general, I’ve felt quite calm about the whole situation.”

The Cares Act did include temporary provisions meant to keep Americans employed, notably a Paycheck Protection Program that offered $349 billion in potentially forgivable loans. But it implemented all sorts of restrictions—companies had to hire back 90% of their workforces and use the money within eight weeks, for example—and was designed to end on June 30. The rest of the Cares Act focused on what to do once millions of people were already out of work, adding $600 to states’ weekly unemployment payouts and creating the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program, which allowed 57 million self-employed, freelance, and contract workers to qualify for unemployment insurance for the first time. It also sent a one-time $1,200 check to adults whose income was below a certain threshold last year, plus $500 per child.

There was a big difference, though, between what the Cares Act offered and what many people experienced. Take unemployment insurance. It’s a complex partnership whereby states administer the payouts while the federal government covers some of the administrative costs, such as payroll and tech support. In recent years, many states have cut unemployment insurance funding dramatically, while federal contributions have been funded through a payroll tax stuck at the same level—6% of a worker’s first $7,000 in salary—since 1983.

“During the 2008 recession we had 2,200 employees. Right now we’re at about 1,000,” says Kersha Cartwright, director of communications at Georgia’s Department of Labor. “We’re hiring folks, but we don’t have time to train them. All of us are helping customers.” In one month, the state processed 1 million unemployment claims, which worked out to about 1 in 7 working-age Georgians. But there was a backlog of many more.

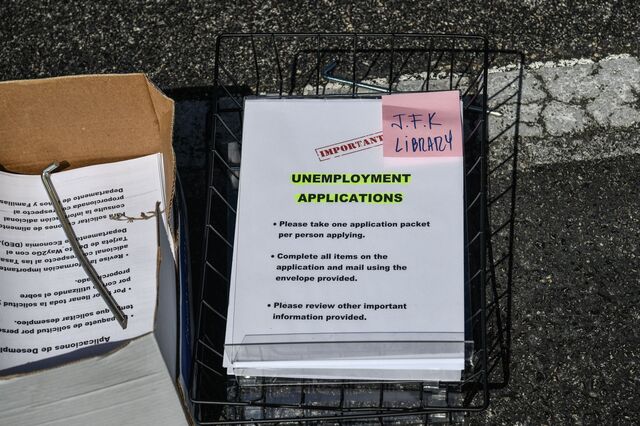

Across the country, decrepit state websites crashed. People spent hours filling out forms, only to lose their work. At one point, Florida’s online and phone systems were so overwhelmed, the state asked people to mail paper applications instead. In Illinois, the De Swardts spent a week trying to get the unemployment website to work. “We tried for a couple days,” Bennie says. “I finally got up early one morning—”

“Six o’clock,” Chrissy interjects.

“I clicked and clicked, and at about 8 a.m. I got through.”

The PUA fund they and other freelancers have been applying for is designed to expire on Dec. 31. Some states, such as California and New York, incorporated it into their existing unemployment application process. Others asked people to first apply for regular unemployment, get formally denied, and then reapply for the new fund, delaying payments and causing widespread confusion.

Three weeks after the De Swardts applied, Chrissy was notified that she’d qualified for $741 a week (including the $600 from the Cares Act), before taxes. She didn’t understand why it was so low. “There’s no explanation, just a deposit in the bank account,” she says. Bennie didn’t hear anything at all.

The 40 million people who’ve filed for unemployment so far are just a portion of those out of work. Tiffany Black isn’t counted in that figure, even though she was among 1,900 employees laid off by Airbnb Inc. on May 5. Black, who’d been a senior marketing manager at the company’s headquarters in San Francisco, hasn’t applied for unemployment because Airbnb is paying her severance until July 6. Once it runs out and she has to rely on the state program, she’ll be in trouble. California’s average unemployment payment is $338 a week—not enough to live on in the Bay Area—and the $600 Cares Act bonus ends right around the time she’d likely start receiving payments. “You’re going to have all these tech workers and other salaried people needing help right as this runs out,” she says. “I don’t think anyone realizes that yet.”

Last year, Black gave up a more expensive apartment closer to her former office, but even the cheaper one she found outside the city costs $2,000 a month. She’s also $45,000 in debt from a failed attempt to start her own business last year. She plans to look for a new job, but if that doesn’t work out, “I’m going to have to pack it up and move home to New Jersey and live with my mom,” she says. “I’m 40 years old.”

Also uncounted in unemployment statistics are those who’ve found the system too daunting. “I looked into unemployment insurance, but I can’t tell if it applies to me,” says Tabitha Driver, a 21-year-old housekeeper and hairstylist in New Ulm, Minn. When the freelancer tried to apply for unemployment in early April, the website said the state was waiting for guidance on PUA from the federal government. Because her parents claimed her as a dependent on last year’s tax returns, she wouldn’t be getting a $1,200 stimulus check, either. (Her parents got the $500 bonus for her, but her mom is also out of work now; she told her parents to keep the money.)

Driver is among the estimated 28% of Americans without savings. “I have zero income. None,” she says. “I have rent due. Bills. I can’t pay any of it. I’m running low on dog food.” She started a GoFundMe page to cover her April rent, but no one donated. Then she started tweeting at celebrities. She asked YouTube stars for money. She replied to random Twitter accounts that claimed to be giving away cash to anyone who followed them. When the pop culture writer Shea Serrano offered $100 to anyone who could tell him the score of the shooting contest in the movie White Men Can’t Jump, she dug up the answer and sent along her Cash App handle. (She didn’t win.) She tweeted dozens of times a day for weeks.

One of her favorite accounts to solicit was that of Detroit real estate heir Bill Pulte, who last year started distributing money to needy people online, a movement he dubbed Twitter Philanthropy. He persuaded some wealthy friends to do so, too. “We’re like this shadow group of philanthropists who’ve stepped up to help people in the absence of functional government,” he says.

Before Covid-19, Pulte mostly pulled one-off stunts, like the time he offered to donate $30,000 to a random military veteran if the president retweeted him. (Trump did, and Pulte kept his promise.) When the coronavirus started pushing people out of work, though, Pulte began receiving thousands of desperate pleas, a new one about every 10 seconds. So far he’s given out about $81,000, he says, mostly in small payments to help people buy groceries or, in at least one case, order a pizza for dinner. (“Take a picture of you with the box!” he tweeted.) Driver never could get his attention, but someone else saw one of her tweets and sent her $450. Other strangers chipped in with an additional $100. So far, that’s all the assistance she’s received.

In Montana, Anderson found himself lost in a bureaucratic maze. Sales at his Jiffy Lubes were still down 30%, and he’d had to reduce his workers’ pay. In the early days of the shutdown he’d applied for an Economic Injury Disaster Loan, a program originally created to help companies affected by natural disasters. Three weeks later, he received an email instructing him to reapply. He called the U.S. Small Business Administration, which administers the program, and was told that he’d have to reapply because the Cares Act had changed the rules—and also that he shouldn’t bother, because the fund was out of money and the SBA had stopped accepting applications. After the program was refunded and restarted, Anderson called the SBA and was told he was still in the queue. In mid-May, almost two months after he applied, he received $10,000.

He had better luck with the Paycheck Protection Program. He applied on the program’s first day, and three weeks later he received $250,000, enough to bump his staff back up to full time. “I was lucky,” Anderson says. “It ran out of money literally the next day.”

In Nashville, Bernstein applied for a PPP loan, too. Rising wholesale orders from grocers for Bongo Java’s coffee beans hadn’t made up for declining ones from local restaurants or for the lost income at his cafes. He’d deferred some of his April rent payments and was in talks with the local YMCA to provide lunches for kids during the summer. The deal hadn’t gone through yet, and he was fast running out of money. He and his wife tore down their garage, built an apartment, and rented it out. They stopped contributing to their retirement funds.

His PPP money still hadn’t come in when the fund dried up. After the program restarted with an additional $310 billion, his bank told him he’d been approved. In early May, Bernstein received $930,000, but when he learned what he’d have to do to ensure the loan was forgivable—rehire his employees and use it all within eight weeks—he concluded it was useless. “I can’t convince people to come back to work for eight weeks and then tell them to go back on unemployment. They don’t want to go through that process all over again,” he says. “I’m going to have to give the money back.”

Given how long the pandemic could last and how quickly the first rounds of stimulus ran dry, the $3 trillion the U.S. government has spent so far likely won’t be close to enough. Congress is working to extend the PPP loan restrictions beyond eight weeks and to soften some of the conditions on how the money is spent. House Democrats, meanwhile, have proposed an additional $3 trillion in relief that would, among other measures, extend the $600 boost in unemployment benefits through January, but Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has balked at the idea, arguing that providing more assistance would “make it more lucrative to not work.” Moves to reopen the economy won’t necessarily help right away, either, because while you can send people back to work, you can’t force consumers to use their services. And that’s to say nothing of the potential for new outbreaks.

“Do I even want the kind of customers who’re willing to come to a restaurant right now?” Bernstein asks. In May, Tennessee allowed restaurants to reopen if they operate at less than 75% capacity, but Bongo Java wouldn’t be profitable under those circumstances, and besides, Bernstein wouldn’t feel safe. “It’s not just safety from Covid at this point. The political divide has also created a security risk,” he says. He mentions the men who carried guns and a rocket launcher into a Subway franchise in North Carolina to protest the state’s stay-at-home measures, and the Family Dollar customers in Michigan who killed a security guard who’d asked one of them to wear a mask. “This whole situation is bringing all these issues to the forefront that no one wants to talk about. Education. Politics. The economic divide in this country, no one can say that doesn’t exist. Do we just keep going as is, or do we as a society do something about it?”

He doesn’t know the answer yet. Like everyone, he’s still in the thick of the story. The panic of March has given way to the resigned acceptance of June. People wake up unsure what day it is, make coffee, eat cereal, and spend hours on hold with government agencies. Some days they feel optimistic. “I was in the Marine Corps,” Anderson, in Montana, tells me. “I have a very pro-America mindset. I really do believe we’re more resilient.” Other days, it feels as though the fallout from Covid-19 has pushed the country to its breaking point. “This is going to exacerbate inequality,” he says a few days later. “The group of losers in this will be large and left behind in some way. That sucks.”

In New Mexico, Lockhart says her savings have run dry. She’s given up her house, and she and her three daughters have moved in with her parents, but six people in a two-bedroom house isn’t sustainable. She did finally apply for unemployment and has looked into low-income housing. She’s also been dating a childhood friend, who offered to let her family move in with him. The hitch is that he lives in Chicago. “He owns his own house. It has extra bedrooms,” Lockhart says. “But according to my divorce agreement, I’m not supposed to take the kids out of state.” She hasn’t decided what to do.

The De Swardts have been out of work for more than three months—longer than they’d estimated their savings would last. Qualifying for unemployment kept the couple from having to tap them. In May, Bennie was finally approved for $440 a week. He also got some money from the Golf Channel, which paid its freelance camera crews through the end of May. Now, though, the De Swardts’ fall events are starting to be canceled. Bennie has considered stocking shelves in an Amazon warehouse, but Chrissy doesn’t want him to—she’s worried he’ll contract the virus.