Hong Kong protests: could a financial crisis be the jolt that brings the unrest to a halt?

- While Hong Kong’s economy fell into a worse than expected recession last quarter, financial markets have remained resilient

- A run on a major bank or a serious challenge to the currency peg might push Beijing, the Hong Kong government, protesters and ordinary Hongkongers to seek a resolution

It was the most widely anticipated piece of economic data. Yet, when it was finally published last week, even analysts were taken aback.

However, as the government stressed in its press release, it was only after the mass protests erupted in early June that Hong Kong’s economy registered an “abrupt deterioration”. Make no mistake, the damage was mostly self-inflicted.

Still, some sense of perspective is in order. To claim, as one economist did in an interview with Bloomberg, that the downturn is “obviously comparable to the global financial crisis” is deeply misleading.

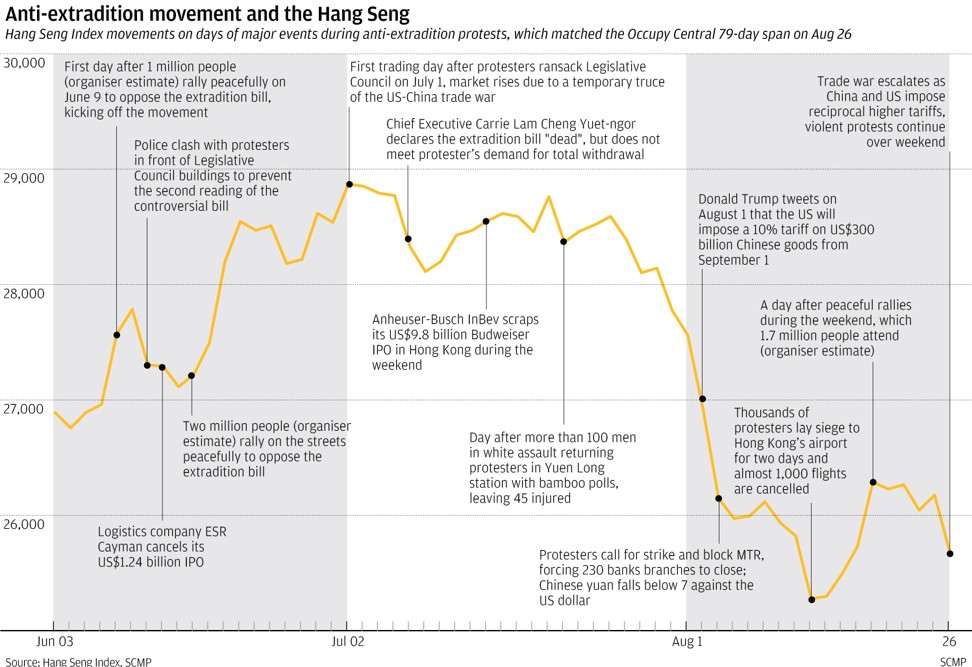

First, the contraction in output in Hong Kong at the end of 2008 and in early 2009 stemmed from severe stresses in the global financial system triggered by the demise of Lehman Brothers. Asset prices and interbank markets in the territory came under intense pressure, undermining confidence in an economy heavily reliant on trade and financial services. In 2008, the Hang Seng Index plunged almost 50 per cent.

The world is awash with liquidity, the banking system is much more robust and asset prices are at elevated levels, with the benchmark S&P 500 index hitting a record high last week.

Despite city’s woes, workers can expect 3 per cent pay rise next year, survey finds

Still, while Hong Kong’s considerable financial buffers are helping prop up asset prices, the lack of any significant pressure from markets is, regrettably, exacerbating the political crisis.

To be sure, no sensible person would wish a financial crisis on Hong Kong. Moreover, it is unclear what impact such a calamity would have on the city’s deeply polarised political environment, and, crucially, what Beijing’s response would be. Yet, the absence of severe market pressure is helping fuel the conflict by depriving Hong Kong of a much-needed catalyst to break the cycle of ever-increasing violence.

Top official warns of another forecast downgrade for Hong Kong economic growth

Right now, the stability of the financial system is emboldening the protesters, especially the militant ones, to dig in their heels. It has also reduced pressure on the government to meet their core demands by making it easier for it to claim that its hands are tied by Beijing.

China, for its part, is more inclined to let the conflict play itself out in the hope that ordinary Hongkongers will reach a point where they have had enough of the violence and chaos.

The fact that Hong Kong’s financial system has been largely insulated from the unrest is a testament to the strength of the city’s creditworthiness. Yet, the relative calm in markets does not make a resolution of the crisis any easier.

Nicholas Spiro is a partner at Lauressa Advisory