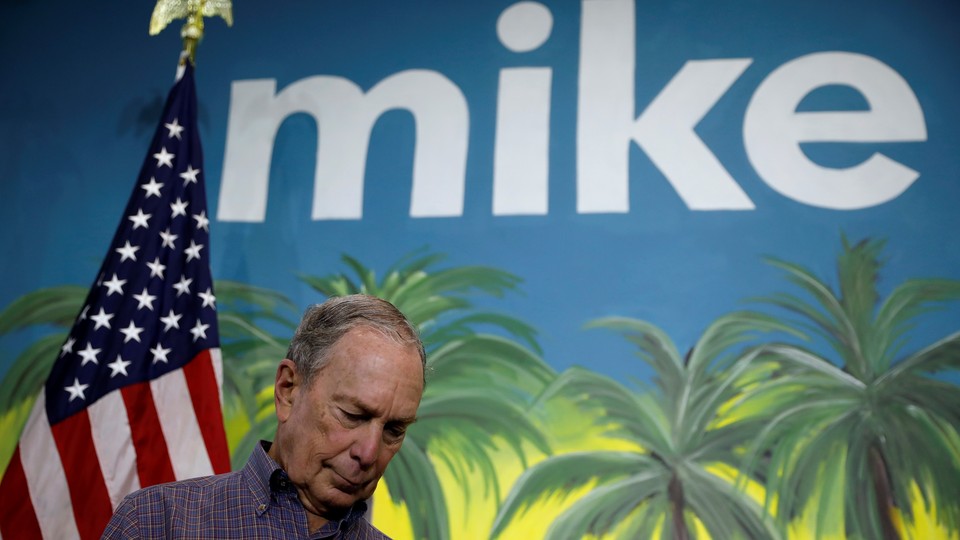

Why Michael Bloomberg Spent Half a Billion Dollars to Be Humiliated

The former mayor of New York spent $500 million in 16 weeks, then dropped out less than 12 hours after polls closed on the first day he was on the ballot.

When Joe Biden walked into the Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma, Alabama, on Sunday, the crowd welcomed him to a seat behind the pulpit like he was Norm walking into Cheers.

Michael Bloomberg had been sitting in the front pew for two hours already, the only candidate there from the start of the service. The pastor had introduced him from the altar by telling a story about how Bloomberg initially didn’t want to come. About 10 people had waited until Bloomberg started speaking to stand up and turn their back to him in silent protest. He’d passed around a tin of Altoids (original flavor) to the people sitting next to him. He’d stood for the hymns, just listening.

When Bloomberg got up to speak, he laid the narrow notecards he uses atop an open Bible. He talked about his record as mayor of New York City, and about working with the Reverend Al Sharpton, the New York–based civil-rights leader who preaches at the church every year on the anniversary of Bloody Sunday. But Sharpton wasn’t there to hear it, because he’d taken Biden for a private tour of a memorial nearby. The only time Sharpton spoke publicly about Bloomberg that day was to rib him to put some money for church renovations into the collection basket.

The billionaire chuckled; he’d already pulled two bills from his wallet. He put them in the basket—another few bucks toward what must be a record for the largest amount of money spent in the shortest amount of time with the least to show for it. Bloomberg spent $500 million in 16 weeks, and dropped out less than 12 hours after polls closed on Super Tuesday, the first time he was on the ballot.

Why, when you’ve got $60 billion and you’re a 78-year-old Jew, would you spend so much of your Sunday sitting in church in Alabama? Because reaching out to voters, especially in a historically and emotionally important place like Selma, is what running for president demands. So Bloomberg did it, even though that meant sitting silently while the hometown congresswoman, Terri Sewell, looked out at the congregation and said that Biden isn’t rich, but he’d “earned” his spot in the church.

Remember one month ago, after the Iowa caucus collapsed, and Biden’s campaign was trying to explain how coming in a distant fourth there wasn’t a problem, and neither was coming in fifth in New Hampshire? The Bloomberg campaign was putting together the kind of on-the-ground operations pitched to potential hires as “Think about getting to do everything you’ve ever wanted to in a campaign.” Then Biden won South Carolina, a single state that he was always expected to win (though he won by a margin larger than he had dared hope), and the chin-strokers and anti–Bernie Sanders panickers instantly transformed Biden into a juggernaut.

It was enough. By the time Bloomberg took his seat in the pew, his top aides and most prominent supporters had started to realize that the implosion of his campaign couldn’t be stopped. It’s like Bloomberg was playing blackjack with a 16—maybe good enough to win, but he was still nervously waiting to see what the dealer flipped over. That was the optimistic take.

Most of Bloomberg’s campaign was a tight operation, complete with the former police detail he hired as private security (they wore earpieces and green lapel pins with eagle heads on them to help look the part of the Secret Service, which isn’t protecting any of the Democratic candidates yet). A veteran of both Clintons’ campaigns, whose company has mastered everything, down to the lighting that makes even iPhone pictures look good, ran logistics. But the Selma visit was a mess. Instead of anyone organizing the four presidential candidates and thousands of people in attendance ready to re-create the 1965 walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, there was just a man shouting half-directions into a megaphone and another standing in front of those waiting to march doing an uncanny impersonation of Martin Luther King Jr. delivering his “I Have a Dream” speech. Bloomberg’s staff walked him to a spot at the front of the crowd that they thought had been set aside for him. But it hadn’t been. Biden had left, Sanders was never scheduled to come, and Elizabeth Warren, Pete Buttigieg, and Amy Klobuchar were jammed together halfway down the block where they were supposed to be. A woman trying to take control chased after Bloomberg and his team: “This is not the line!” she said. “This is not the front of the line!”

So Bloomberg’s team walked him back to where the other candidates were, and shoved him in with everyone else. But Warren and Klobuchar held on to each other, pulling through the crowd at one point. Buttigieg attached himself to Sharpton. The billionaire in the suit with the thread count so high you could see it was left without his fellow presidential contenders once again, accompanied by people who had joined him in church, including Columbia, South Carolina, Mayor Steve Benjamin. “Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around,” the crowd started to sing, and Bloomberg began to move, sort of, shuffling along in his black tasseled loafers. A woman called out to ask him to fund a museum for one of the women who’d led the Bloody Sunday march. He didn’t seem to hear her.

A top aide assessed the chaos, the way Bloomberg was getting bumped around, and offered to pull him out and take him to his waiting plane.

“We don’t have to do it,” he told Bloomberg. The candidate dismissed that immediately. “We have to go over the bridge,” he said. His staff pulled him forward. Tom Steyer’s wife, Kat Taylor, had just finished singing an Aretha Franklin song, and Steyer, who’d driven six hours overnight from South Carolina after dropping out the day before the gathering, was on the mic talking about how he wanted everyone to know that he supports reparations.

Bloomberg pushed ahead. He went over the bridge.

The first time I wrote a story taking Bloomberg’s presidential plans seriously was in October 2007. He was gearing up to run as an independent. I talked with then-outgoing Senator Chuck Hagel of Nebraska about him possibly being Bloomberg’s running mate, and didn’t get a no. Moderates and independents were having visions of a candidate who could appeal across the usual political divisions, and of an unlimited spending bonanza. Some were speculating about what Kevin Sheekey and Patti Harris, then Bloomberg’s top advisers (and still riding on the plane with him yesterday), would be able to pull off at the national level. Bloomberg’s team talked about laying low until late in the race, then having him come in as a potential savior. “The country’s in big trouble and someone’s got to pull it out,” I quoted Bloomberg saying at the time.

In 2016, Bloomberg again worked up a whole plan to run as an independent, and to try to force a split Electoral College so that the House of Representatives would get to pick the president instead. But four years ago, almost to the day, he pulled the plug at the last minute, deciding that it wouldn’t work. “It weighed on him,” one person who was involved told me at the time, “but at the end of the day, the fact that this was probably the last shot wasn’t enough to make him want to do it.”

He then decided he actually had one last last shot. Somehow, everything about politics has changed, and he showed up this time as a Democrat, telling Democrats what he thought Democrats should do, but not knowing quite what to do when they fired back.

On Sunday night, he was in San Antonio, Texas, in an old airplane hangar that had been turned into an event space. There was a six-piece mariachi band onstage. There were three food trucks (barbecue, tacos, and hamburgers) that had been paid well enough to hand everything out for free. Sitting on the open bar, there was a bowl of Texas-specific Bloomberg campaign buttons. And there was Bloomberg, giving the kind of no-frills speech he’s best at. (No one has ever voted for him for the razzmatazz.) “He has fight in him,” Connie Reyna, a 56-year-old medical transcriptionist in a Make Mother Earth Great Again cap, told me, and then added, not even realizing how much his slogan (“Mike can get it done”) had been drilled into her by all the advertising, “I think he can get it done.”

“Mike! Mike! Mike!” the crowd chanted. At one point, when he mentioned Donald Trump’s impeachment, a few yelled “Lock him up!” and Bloomberg laughed, almost giggling. He said he’d flip the state. “Blue! Blue! Blue!” they shouted. He was having a good time. Never much of a handshaker, he did one round of working the crowd, then turned before going out the door and did another. The next morning, having flown to Washington, D.C., he was even more in his element, in front of 18,000 at the national conference for the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, the pro-Israel lobby, people who probably didn’t catch the error when he said that Jews “can’t even agree who’s the funniest New Yorker: Jerry Steinfeld, Larry David, or me.”

By the time Bloomberg arrived at George Mason University for a Fox News town hall on Monday evening, though, everything seemed cooked. Sheekey and Harris, the latter in an embroidered Get It Done shirt, watched from a balcony, a few feet away from the reporters they’d let in to watch the event live. Bloomberg is more at ease in a town-hall format, and he seemed to be winning over the audience by talking about management expertise and the vagaries of interest rates. At the first commercial break, he sat silently on his high-top chair until people started calling out to him for photos. Then he eagerly worked the crowd.

Later, a question about guns came up, and a man in an orange Guns Save Lives hat stood up and started yelling at Bloomberg. Everything broke down. Four protesters stood up, waving homemade LGBTQ-rights flags and yelling at him to release former employees from nondisclosure agreements that they’d signed with his company (and that Warren had hammered him for on the debate stage in Las Vegas). The man who’d been shouting about gun rights was angry.

“We don’t do that; we don’t protest!” he yelled at the gay-rights protesters as Fox News security took them out but left him in his seat. Bloomberg promised to talk with him after, and the hosts quickly went to break. In the room, the chaos continued.

“Thank you for saving our children’s lives!” a woman called out.

“What are you talking about? He’s for infanticide! He’s for full-term abortion!” another woman yelled back.

The viewers at home didn’t see the couple hundred people who cheered and applauded him. That was the core of Bloomberg’s problem. People showed up at his events and shouted “We like Mike!” Elected officials endorsed him. But to many of the people who care the most, the most active and noisy, Bloomberg is just wrong—about guns, about abortion, about soda sizes, about whatever. “He’s a moderate, protested by the left and the right—you can use that,” a campaign aide told reporters as we headed out of the town hall, trying a cheery spin.

Bloomberg started yesterday morning in Little Havana, Miami, annoyed. He knew all the questions would be about whether he’d drop out, and he’s never been a man who takes criticism well. Biden hadn’t changed, nor had Bloomberg’s assessment of Biden as weak and unelectable. But Biden didn’t look weak, and hard-core Democrats really wanted to believe that he wasn’t. So Bloomberg was supposed to drop out—and unify a party that doesn’t seem to care how much it owes its current power to his money. He wasn’t helping Sanders by staying in, he insisted: “I’m trying to help myself.” Asked if he’d come in third on Super Tuesday, he said, “There’s only three candidates. You can’t do worse than that.” And when someone pointed out that he’d forgotten about Warren, he said, “I didn’t realize she’s still in. Is she?” Asked if he should drop out, he said, “Joe’s taking votes away from me. It goes in both directions. Have you asked Joe if he’s going to drop out?”

Then he got on a charter plane to Orlando, to visit a field office and to lay a wreath at the Pulse nightclub with the moderate-Republican parents of a victim of the June 2016 shooting there, the kind of folks his campaign was supposed to (and did, for a time) attract. A few hours later, he arrived at what was meant to be a victory party in West Palm Beach, down the road from Mar-a-Lago—the latest troll of Trump in a campaign that intentionally, and repeatedly, mocked the president. Instead, Sheekey, the former mayor’s campaign manager, was making an aggressively ambiguous prediction to reporters as polls closed: “Mike Bloomberg is either the candidate for the party or the single most important person helping that candidate defeat Donald Trump.”

When Bloomberg showed up at the victory-party-that-wasn’t, the crowd was ecstatic. There were 2,200 people, including Judge Judy, waving American flags and cheering his name, all of them captured by a crane camera. He gave a speech as if he were the one who’d just done the trouncing, even though the crux of that speech was insisting that it didn’t matter how many delegates he won.

Bloomberg finished the night with what seemed to be a genuine smile on his face. Many of the people working for him finished the night trying to figure out if they were rooting for some way for him to continue, or for being able to start planning the vacations they could afford with the money he was paying them.

“You can’t be a fucking savior,” a very involved Democratic donor who’d been heavily skeptical of Biden and curious about Bloomberg told me over the phone on Tuesday morning, “and then be a dud.”

So: Why did he do it? He really wants to be president. He has for years. The reason he never ran before is that he didn’t want to lose. He didn’t want to be embarrassed. And in the end, he finished last night winning American Samoa. He probably could have bought American Samoa for all he spent.

This morning, after Bloomberg decided to quit the Democratic race, I remembered a moment in Little Havana yesterday. Bloomberg had agreed to hold a constituent’s young daughter for a photo. He tried to smile and make it work. But she wouldn’t stop squirming.

“All right,” Bloomberg said to her father as soon as the photos were done. “All yours again.”