How bitcoin and cryptocurrencies went from Wall Street to the high streets of Southeast Asia

Cryptocurrencies are no longer the sole domain of hedge fund managers and high-stakes traders – in Southeast Asia they are being used to solve the financial problems of working men and women

It is hard to say if Sachaknisay Sov is rich or poor. He lives in a rented room in rural Cambodia without a kitchen, but he does have something in common with many millionaires.

Sachaknisay Sov uses a virtual currency similar to bitcoin. This year, when the taxi driver, 31, was looking for a way to pay bills and afford repairs to his motorcycle, he took a US$500 loan in the form of digital tokens that could be traded for cash in selected pawn shops.

“[Digital token-based loans are] absolutely much better than the traditional ones,” said Sachaknisay Sov, who used to borrow money from friends and local lenders. “It has a lower interest rate.”

Previously, he paid at least 18 per cent interest for every penny he had borrowed. Now, he pays 5 per cent.

WATCH: What are cryptocurrencies?

Sachaknisay Sov represents an emerging group in the developing world as cryptocurrencies have made their way from Wall Street to the high streets of Southeast Asia.

For years, cryptocurrencies have made newspaper headlines for their potential to generate wealth. For instance, the value of bitcoin, the most recognised digital currency, grew about 1,500 times over five years to reach US$20,000 in 2017.

But in Southeast Asia, digital currencies are becoming increasingly popular for another reason: they are helping businesses tackle everyday problems.

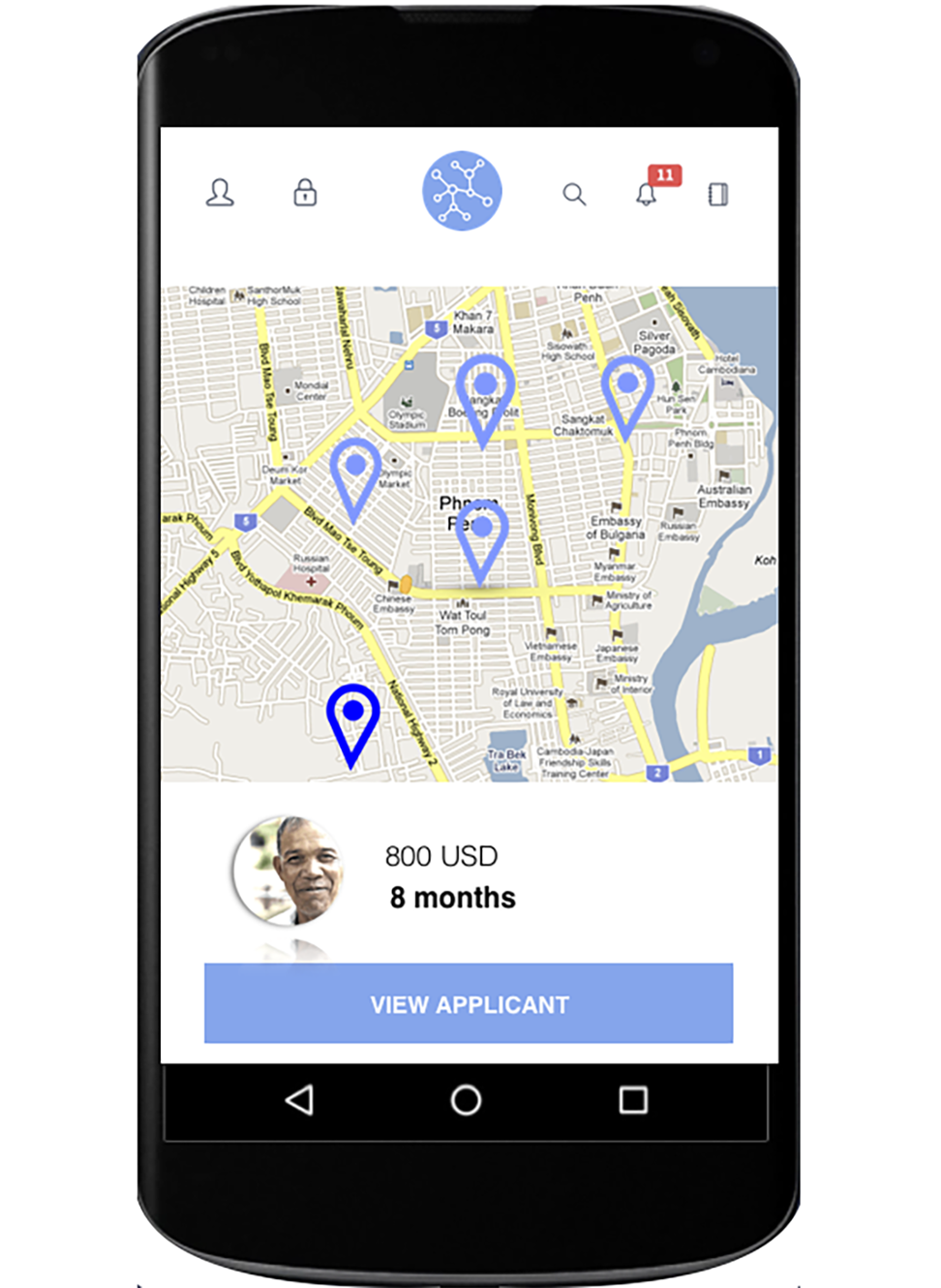

One such business is DApact, a microloan provider in Phnom Penh. Unlike most financial institutes in Cambodia, which frequently conduct internal audits, DApact relies on the traceable character of digital currencies. It works this way: every digital token used by DApact carries a unique code. When the token is transferred via a mobile app, its entry and exit points are recorded and require no manual check. DApact says this enables it to run its business at a third of the cost of traditional practices. That saving translates to a lower interest rate for borrowers – in this case, mostly poor villagers.

Its methods have also made DApact popular with international aid agencies and investors. “For those lenders, transparency is very important,” said Pierre-Marie Riviere, the company’s co-founder. “What we offer them is total control of every step of the [money lending] process.”

Forget China: Hong Kong, Singapore are new kids on the blockchain

The one-year-old start-up has already launched two pilot projects near the Cambodian capital, testing its business model with villagers and local pawn shops. The pawn shops act as currency exchange agencies, which take in digital tokens and give away fiat currency. They also help collect repayments. All 30 borrowers have paid back their loans, Riviere said.

The sharp contrast in villagers’ low economic status and high engagement in the digital sphere is not unique to Cambodia.

Global consulting and auditing agency KPMG estimated that in 2016, seven in 10 people across Southeast Asia did not have a bank account. But people in the region spend more time on their smartphones than their counterparts in the United States or Europe, according to a 2017 report by Google and Temasek. For Manila-based company Coins, that is a huge business opportunity.

There are an estimated 2.2 million Filipinos working overseas, most of them using remittance services to send cash to their families back home. But these services skim off some of the cash in cross-border fees.

The bitcoin party is over. The blockchain party has only just begun

However, an app introduced by Coins in 2015 that allows workers to cash into bitcoin before transferring the digital money home greatly reduces these fees.

For instance, it costs no more than US$4 for a Filipino caregiver to transfer US$200 from the United Arab Emirates to the Philippines using Coins, while that figure is US$8.52 through Western Union, the largest remittance company in the world, according to the World Bank.

In Myanmar, where investors are few and far between, local start-ups have raised US$10.5 million through initial coin offerings (ICOs), according to the website ICO Watchlist.

An ICO is a digital token-based fundraising mechanism through which companies create and sell their own virtual currency in exchange for cash or widely accepted cryptocurrencies. The buyer can use it to pay for goods or services the company offers, or stash it away as an investment.

James Song, the founder of ExsulCoin who recently completed US$4 million worth of fundraising for his refugee-focused business, favours ICOs for their “speed, scale and autonomy”.

US$1 billion down, why is Japan still in love with bitcoin?

In Cambodia, fintech start-up CryptoAsia has developed an app which allows businesses to accept bitcoin payments and be paid in US dollars. At least nine enterprises have signed up, including a black pepper farm in Takeo Province.

And another cryptocurrency-based fintech firm, MicroMoney, has expanded its microloan network from Cambodia to Myanmar, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand, with more than 110,000 registered users, according to the company website.

But despite the growing popularity of digital currencies, many businesses are yet to fully embrace their potential. Rithy Thul, an entrepreneur who has long hoped to provide digital token-based remittance services for Cambodians working overseas, is put off by a lack of clear regulatory oversight. While the Cambodian government has not banned the use of digital currency, neither has it expressed support.

Others see cryptocurrencies as inherently risky. Some experts question whether economically vulnerable groups can withstand the volatility of digital currencies – last year, bitcoin’s value plummeted by nearly 40 per cent. Others worry villagers with little financial know-how may be easy prey for scammers and cybercriminals.

Why is South Korea suddenly terrified of bitcoin?

Even so, many believe the business outlook remains positive. As Thul put it: “Digital currency is not perfect, but it is the most perfect money poor villagers have ever had.”

Sachaknisay Sov, the taxi driver in Kean Klang village, agreed. Since he first took out a digital token-based microloan in March, he has become a marketing volunteer for DApact.

“We told others that DApact has the best service in Cambodia. It has helped lots of Cambodians get a low-interest loan.” ■