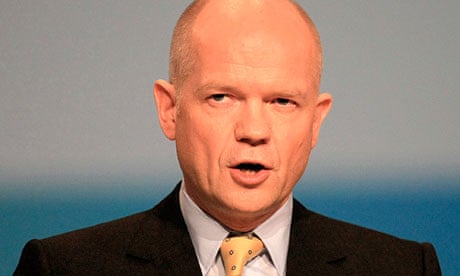

On Wednesday, William Hague will host a meeting of foreign ministers from the G8 group of rich countries paving the way for a gathering of the countries' leaders in June. The existential threat presented by Iran and North Korea is on the agenda for both. But the real and present danger of climate change will not be discussed at the leaders' summit.

It was recently revealed that David Cameron's adviser for Europe and global issues, Ivan Rogers, blocked moves from Germany and France to make climate change a G8 agenda item. This is short-sighted and risks undermining the last hope for an international agreement that could avert catastrophic climate change.

According to Faith Birol, chief economist at the International Energy Agency, the world has just four years to implement the changes necessary to avoid a temperature increase above 2C. If we wait any longer, we will lock ourselves into high-carbon infrastructure that takes us above this threshold. Two degrees constitutes a level of warming referred to as a "dangerous" by scientists. All major countries agreed in Copenhagen that temperature rises should be limited to below this level.

In two and a half years' time, world leaders will meet in Paris under the auspices of the United Nations to thrash out a deal to make good that promise. Despite the disappointment of Copenhagen, there has been plenty to suggest that a global deal is possible.

The world's largest emitter, China, is taking this agenda seriously by launching seven pilot schemes this year ahead of a national roll out in 2015-16. This forms the key part of its efforts to reduce greenhouse gases per economic unit by as much as 45% before the end of the decade. Meanwhile, investment in Chinese clean energy rose 20% last year, according to Bloomberg.

In the US, trading on the California carbon market began on 1 January while nine north-eastern states have been participating in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative for six years. Last summer, Australia launched its own carbon pricing regime which led to a 9% drop in emissions from power plants in just six months. Diplomats are looking at ways to link the scheme to the EU emissions trading scheme which would bring business to the UK since, according to Intercontinental Exchange, 91% of emissions trading takes place in the City of London.

Countries in every continent have now launched or are considering a carbon tax or cap-and-trade system. In addition to New Zealand and Japan's systems which are already under way, Russia, Thailand, South Korea, Vietnam, Chile, Costa Rica and Mexico all announced plans in the last year.

But bringing these schemes together and reaching agreement in 2015 is still a long way off. To reach a deal, concerted focus and leadership will be necessary at every gathering of international leaders.

Last year William Hague appeared to agree and wrote: "David Cameron's great ambition to lead the 'greenest government ever' relies heavily on a Britain that is leading the way on the world stage, pressing for determined and united global action, setting an example to other nations, cajoling those who do worse and aspiring to match those who do better."

But there are now concerns that the UK government may be watering down its and Europe's own ambition. As well as blocking efforts to introduce a target to decarbonise the UK's power sector by 2030, George Osborne is now understood to be pushing for slower ambition across the EU by opposing a new renewables target to replace the current one which will expire in 2020.

The foreign secretary has an opportunity this week to wrestle this critical agenda from the Treasury to the Foreign Office. Without the G8's leadership, our last chance for ambitious international action may pass us by.