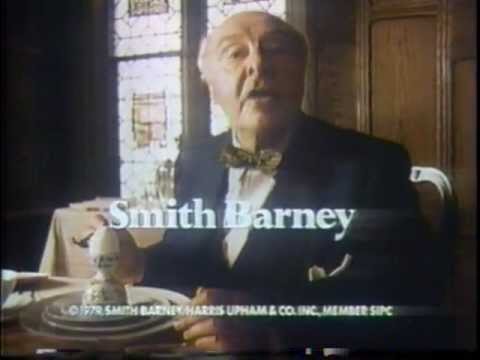

Over thirty years ago, the actor John Houseman intoned about brokerage firm Smith Barney: “They make money the old-fashioned way. They earn it.”

A recent decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit may result in a test of whether the Securities and Exchange Commission can prove an insider trading case the old-fashioned way – by putting on a circumstantial case built around a well-timed trade and contacts with an insider.

In 2006, the S.E.C. sued Nelson J. Obus, Peter F. Black and Thomas B. Strickland for insider trading related to the purchase of shares of SunSource shortly before the announcement of a takeover by Allied Capital in June 2001. The trade generated a profit of about $1.3 million. Mr. Strickland worked for GE Capital, which financed the takeover, and conducted the due diligence on the deal.

Unlike recent cases featuring wiretaps and recordings made by cooperating witnesses, the S.E.C.’s charges boil down to a classic situation of “did they or didn’t they?”

The defendants deny they traded on confidential information. But the timing of the trade is certainly suspicious, and comments made by the defendants about a possible deal raise questions about whether they knew about the transaction ahead of time.

Chang W. Lee/The New York TimesNelson Obus has been fighting charges of insider trading for 10 years.

Chang W. Lee/The New York TimesNelson Obus has been fighting charges of insider trading for 10 years.The district court threw out the S.E.C.’s case in 2010. But the appeals court reversed that decision, holding that the S.E.C. had gathered enough evidence to raise factual issues about the trade.

In any circumstantial case, the evidence is subject to interpretation, so sorting out what really happened will be difficult – especially when each side offers a diametrically opposed view.

The case centers on a conversation in May 2001, when Mr. Strickland spoke with Mr. Black, a college friend, who worked for the hedge fund Wynnefield Capital. According to Mr. Strickland, he did not mention the likely takeover of the company, and only talked to Mr. Black as part of his due diligence by disclosing that GE Capital had an interest in a potential transaction with SunSource. The S.E.C., on the other hand, has claimed that Mr. Strickland tipped Mr. Black about the impending takeover by Allied Capital.

Mr. Black testified that he told Mr. Obus, the president of Wynnefield, that the conversation led him to infer that SunSource might be involved in a transaction. Mr. Obus, in turn, spoke with the chief executive of SunSource about a possible transaction involving the company.

The recollection of the parties differs markedly. Mr. Obus’s call could be interpreted to mean that he knew something big was in the offing, but whether he was aware of the particulars or was only guessing is unclear. Without a recording of the conversations, the case hinges on the testimony the jury decides to believe.

The timing of Wynnefield’s trade is also subject to conflicting interpretations. The firm bought 287,200 shares of SunSource, or about 5 percent of its stock, on June 8, 2001. That was more than two weeks after the conversation between Mr. Strickland and Mr. Black, but just 11 days before the announcement of a deal that sent SunSource’s stock price up more than 90 percent.

In most insider trading cases involving information about an impending takeover, securities in the target company are bought as soon as possible to avoid getting shut out if word about the deal leaks into the market. That did not happen here, and since Wynnefield was already a significant investor in SunSource it would have been reasonable for the firm to buy more shares. Yet buying 5 percent of a company’s stock a little more than a week before a takeover announcement could be enough for the jury to have doubts about denials that the purchase was not based on inside information.

Mr. Strickland’s conversation with Mr. Black also presents ambiguities that make it hard to determine what really happened. The defendants assert that the call was part of the ordinary due diligence process for a deal. But a key to any extraordinary transaction is maintaining confidentiality to avoid driving up the stock price – and perhaps triggering a bidding war. Due diligence is usually performed in a manner that avoids disclosure to investors, who might take advantage of the information, but the events in this instance may cut in favor of a finding that something may have been leaked.

Whether Mr. Strickland tipped Mr. Black is a different question. An internal investigation by GE Capital determined that Mr. Strickland had violated the company’s confidentiality restrictions, issuing a reprimand and denying him a bonus and salary increase. But the firm did not fire him, or conclude that he had divulged inside information.

To prove insider trading, the S.E.C. has to show that Mr. Strickland breached a fiduciary duty by disclosing the information, knowing that it would be used for trading by the recipient – or at least acting recklessly in sharing the information. If he did disclose the takeover to an old friend as a gift, then that could be enough in itself to show the breach of duty.

But it is not clear that Mr. Strickland’s conduct rose to that level, particularly in light of the fact that GE Capital concluded the evidence did not support a finding that he had breached his duty to the company.

The appeals court reinstated the case because the evidence is equivocal, and since neither side appears willing to back down there is a good chance the case will go to trial. DealBook has reported that Mr. Obus estimated he had spent over $6 million defending the case, far more than his potential liability.

As Mr. Houseman might have said, the S.E.C. will have to earn a verdict the old-fashioned way – by putting on a circumstantial case that a jury finds persuasive.