On Monday, May 9, a trove of information from the Panama Papers will hit the web. Mostly, it will be a list of names.

And that’s a big deal: There’s a battle going on over whether you should have to link your real name to the things you own, unravelling the lucrative industry that has sprung up around creating ”shell companies” to hide the true owners of assets.

This long-running debate was thrust into the public spotlight after a hacker penetrated the e-mail system of a Panamanian law firm called Mossack Fonseca. The still-unknown hacker approached the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, which brought in reporters through the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) to help sift through 11.5 million documents that came from the law firm, which are now known as the Panama Papers.

Last month, the initial splash of stories from media outlets with access to the documents made waves. Most notably, the Icelandic prime minister’s previously unknown links to an offshore company that owned millions of dollars of bonds issued by the country’s troubled banks led to his resignation. Other officials identified in the papers faced awkward questions about their offshore holdings.

But now that the initial batch of Panama Papers stories has been published, what should be done with all the documents? Many media outlets excluded from the consortium, Quartz included, are eager to see the source material. So too are law and tax enforcement authorities around the world. But so far the documents haven’t been released from the database built by the journalists involved in the consortium.

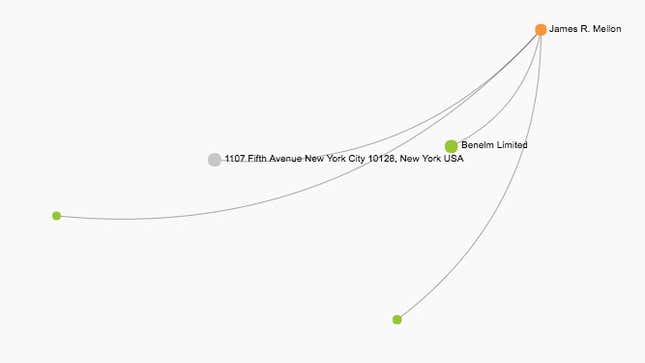

The ICIJ says that next week they will add the information from the Panama Papers to a public database that includes information from a similar, smaller leak in 2013. In most cases it will not be the actual documents, but rather the names of shell companies and beneficial owners that can be gleaned from the files. For example, here’s a visualization from the 2013 database of some offshore companies set up by the heir to the Mellon fortune:

Connecting James R. Mellon to companies like Benelm Limited matters to tax authorities because, before the 2013 leak, all they could see is that Benelm was directed by an attorney in the British Virgin Islands. But as well as revealing the true ownership of shell companies, the 2013 leak also included documents that showed Mellon was moving millions of dollars worth of his inheritance through the companies.

The fear with this new Panama-derived database is that, without access to full documents, reporters and law enforcement won’t be able to understand what these shell companies are doing. But ICIJ must be extremely careful not to reveal too much information about the people in these documents, since shell companies can be used for entirely benign and legal purposes. Hence this disclaimer:

Unlike, say, the Wikileaks database of leaked US diplomatic cables, which made for fascinating reading for the layman, the Panama Papers database will largely matter to investigators seeking to link companies that have already raised suspicions with their true owners, or link people already suspected of shenanigans with the companies that may serve as their conduits for shady dealings.

The secrets of what went on behind closed doors at Mossack Fonseca—including, for example, e-mails revealing that their staff apparently scrambled to destroy evidence of its connections to Argentine corruption—will not feature in the database. For the full extent of those secrets, the public must wait for the consortium—or the court room.