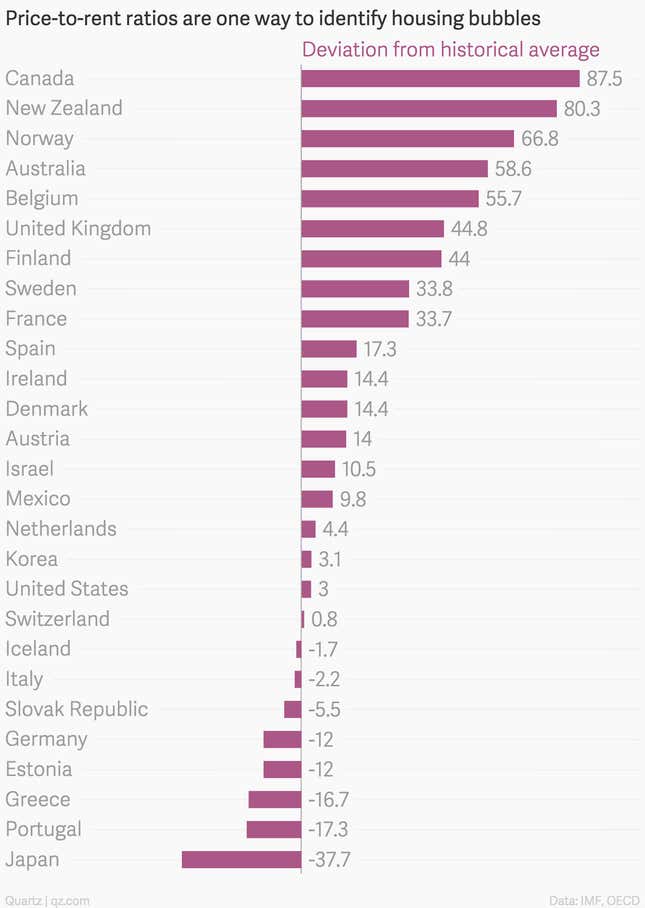

If you’re scanning the world for potential housing bubbles, look down under.

Australia’s residential real estate market has been on fire for years. And the Reserve Bank of Australia’s decision to cut interest rates to record lows will only stoke the flames, with already-low mortgage rates expected to fall even further. Australia isn’t alone. In fact, by some measures, some of the the world’s most overheated housing markets are getting fresh blasts of inflation from national central banks as they try to counter the scourge of the global economy: lowflation.

Recent central bank actions in Canada, Norway, New Zealand, and Sweden all have the potential to stimulate already over-excited housing sectors. In recent months, the Bank of Canada delivered a surprise rate cut intended to serve as a kind of cushion to the shock of sharp oil price declines. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand shifted its monetary stance away from tightening to “neutral.” In December, Norway’s Norges Bank unexpectedly chopped rates. And now Australia has axed its rates, too.

Does that mean all of these markets are doomed to experience nationwide housing busts of the like that the US suffered, when a steep run-up in prices in the mid-aughts gave way to collapse? Not necessarily.

There are differences in housing models across countries. The US, for example, is an outlier among global housing markets in that its mortgages are effectively non-recourse, which means lenders usually can’t come after borrowers if they default and the house isn’t worth enough to pay lenders back. In most other markets, they’re not, which should prevent large swaths of the home-owning public from walking away from their homes if the find themselves underwater, with the value of the house worth less than the loan. Another difference worth noting is how housing is financed. In Canada, until very recently, it’s been based mostly on loans made with customer deposits. The government also plays a very large role, in part through the mortgage insurance required on high loan-to-value mortgages. Such a system looks far more sensible than the wild-west securitization market of the US, which eventually froze up and set off the financial crisis in 2008.

But even if supercharged housing sectors refrain from setting off banking panics, these rising markets can’t last forever, given how unaffordable homes have become. The current state of affairs will also serve as an important natural experiment for policy makers who argue that we can simultaneously stoke the economy with low interest rates and mitigate the risks of financial crisis via so-called macroprudential tools. We’ll just have to wait and see.