/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/43455430/13958986436_124a834fa7_k.0.0.jpg)

In the run-up to the 2014 midterms, a lot of green groups were hoping that this might finally be the election when climate change became a defining issue.

You had billionaire Tom Steyer spending $67 million trying to convince voters to care about global warming. You had the League of Conservation Voters pouring in another $25 million, more than in the previous two elections combined. All the while, some outlets were suggesting that recent natural disasters — from Hurricane Sandy two years ago to the ongoing drought in the West — just might push climate issues to the fore.

Ultimately, none of it mattered very much. The outlook for climate policy looks just as dismal after these midterms as it did before — at least in Washington.

True, there were small shifts in attitude here and there. Some Republicans no longer think it's viable to deny global warming outright. Instead, they dodge and say "I'm not a scientist." And, as Rebecca Leber reports in The New Republic, green candidates are getting better at playing offense. In Michigan, Democrat Gary Peters won his Senate race handily after making climate a top issue.

But there are few signs that the broader landscape is changing dramatically. The next, more Republican Congress will be even more hostile to climate policy than the last one. Global warming remains a low-priority issue in American politics — in a Pew poll, it ranked a lowly 8th (out of 11) on the list of issues voters care about. And, more to the point, it's become an incredibly polarizing topic:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2430266/live-blog-climate-change-exits-tmagArticle.0.png)

That means gridlock on the issue. And that gridlock will have real consequences.

Gridlock is a huge problem for climate policy

In the short term, the election's impact might seem negligible. After all, the action in Washington over the next few years will center on the Environmental Protection Agency, which is crafting rules to cut carbon-dioxide emissions from US power plants. These rules don't need congressional approval (they're being done under the existing Clean Air Act), and President Obama is expected to veto any attempts by Congress to block them. (Conservative governors refusing to implement the EPA's plan may be the bigger pitfall here.)

But congressional indifference is a huge problem for future climate policy. The most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that global greenhouse-gas emissions need to fall 42 to 71 percent below 2010 levels by mid-century if we wanted to fend off the worst impacts of global warming and prevent average temperatures rising more than 2°C (or 3.6°F). That's an astoundingly difficult task. But it gets harder and more expensive the longer that countries delay.

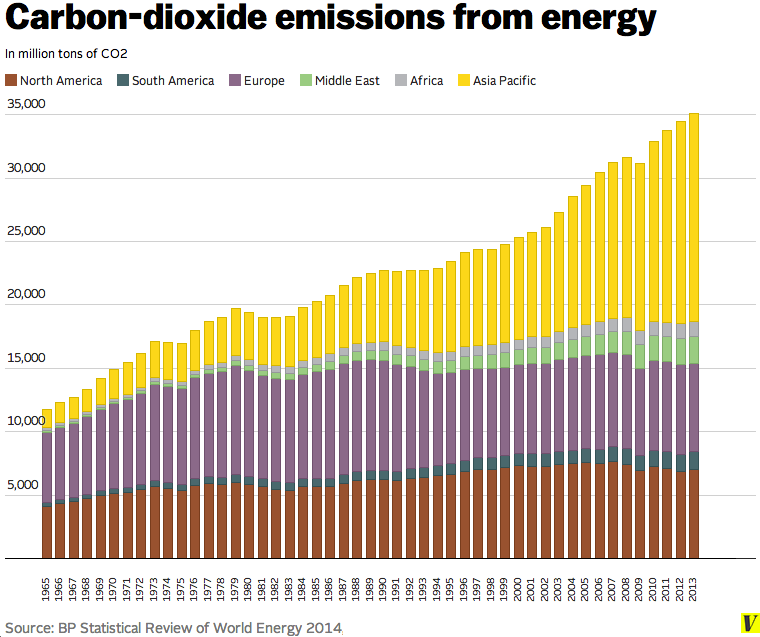

Obviously the United States can't solve climate change on its own. China, India, Europe, and a whole bunch of other nations also need to get on board. But as one of the world's biggest emitters, the US would have to make sweeping cuts domestically to help meet that goal. That would mean tripling or quadrupling the amount of clean energy we use and getting radically more efficient in the way we use energy by 2050.

There is no way the EPA can make that happen. It just doesn't have that much power. In theory, Congress could help get there — via policies like carbon pricing or incentives for cleaner energy. But lawmakers would need to act soon: Even though US greenhouse-gas emissions fell between 2005 and 2012, they're starting to rise again. And the window to stay below 2°C — or even 3°C — keeps shrinking with each passing day.

Without a major global shift on climate policy — and soon — the IPCC was clear on what would happen. At current emission rates, the world is on pace to warm between 3.7°C and 4.8°C by the end of the century, compared with pre-industrial levels. (That's 6.6°F and 8.6°F.) That greatly raise the risk of drastic sea-level rises, crop failures, the flooding of major cities, mass extinctions. Some scientists now worry that a world that hot may not be "able to support society as we currently know it."

The report's bottom line was that countries need to get moving today if they want to stop the planet from heating up drastically. Not tomorrow. Not the day after. And definitely not 10 years from now. But the bottom line of this election is that Congress isn't going to give much thought to climate change these next two years. Maybe not the two years after that. And it doesn't seem to be in the power of either committed billionaires or Mother Nature to get them to do so.

Which means that if anything's going to change, it may have to happen outside Congress. Perhaps new technologies will come along to shake things up (cheap solar, say?). Perhaps states or cities will gin up their own novel ideas for curtailing emissions and adapting to a warmer world. But the 2014 election made clear that Washington, at least, isn't going to be much help on climate policy anytime soon.

Further reading

-- The IPCC explains how to stop global warming, in 7 (difficult) steps

-- These 5 charts show why the world is still failing on climate change

-- And here's a rundown of why UN climate talks keep breaking down

-- Here's a piece by Alexandra Tempus breaking down the politics of global warming even further. One notable tidbit: "in 2014, more than 40 percent of nonwhite Americans believe global warming should be a 'top priority' for their government, while that number for their white counterparts barely tops 20 percent."