/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/34322695/5641586406_f98a71fb3f_b.0.jpg)

All eyes are on Brazil right now because of the World Cup. But there's another Brazil story that deserves just as much attention — over the last decade, the country has made surprising strides in slowing the destruction of its rainforests.

The deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon was one of the biggest ecological disasters of the 20th century. Starting in the 1960s, farmers and cattle ranchers began clearing and burning wide swaths of Brazil's rainforest for land.

Between 1979 and 2005, Brazil lost more than 200,000 square miles of rainforest, an area the size of Spain. That deforestation was a major factor in the rise of greenhouse-gas emissions that cause global warming (all those trees are no longer around to soak up carbon-dioxide)/

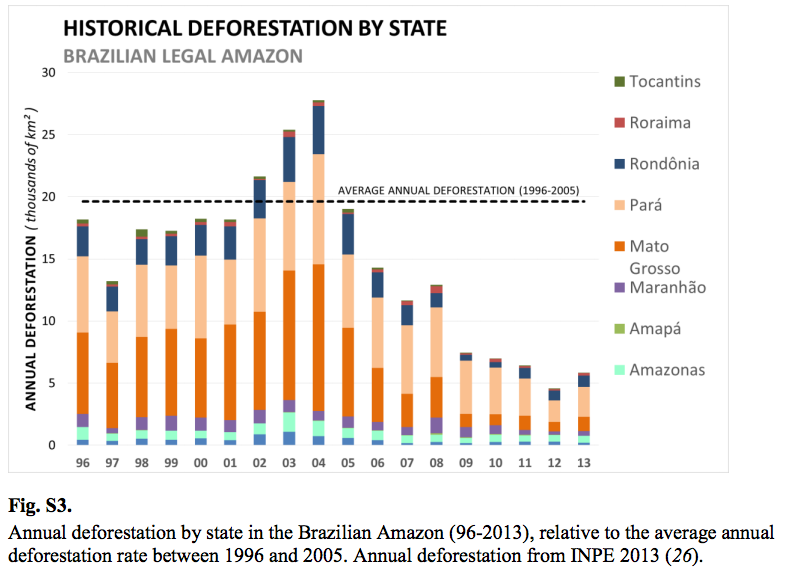

But that's now changing — and dramatically. Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has dropped 70 percent since 2005:

Amazon deforestation in Brazil has fallen 70% since 2005

Nepstad et al, 2014

Between 1996 and 2005, Brazil was losing an average of 7,500 square miles of Amazon rainforest each year. Then deforestation began declining sharply. By 2013, the annual rate of forest loss was down to 2,255 square miles.

It's a major environmental success story, and a key reason why Brazil's greenhouse-gas emissions fell 39 percent between 2005 and 2010 — faster than any country on the planet.

Experts tend to credit a few factors here: Brazil has greatly expanded protection for its forests in the last decade. Perhaps more importantly, the country's soybean and cattle industries came under heavy pressure to quit expanding through deforestation. Instead, farmers and ranchers found ways to boost their yields without cutting down forests for land.

Still, it's not all good news. Brazil's gains have been fragile, with deforestation ticking up again in 2013 and 2014. What's more, the clear-cutting of rainforests is still growing outside of Brazil, particularly in Malaysia, Paraguay, Bolivia, Zambia, Angola and especially Indonesia.

How Brazil curtailed deforestation

So why the drop? A recent report from the Union of Concerned Scientists, as well a recent study in Science led by Daniel Nepstad of the Earth Innovation Institute, give credit to a few different factors here.

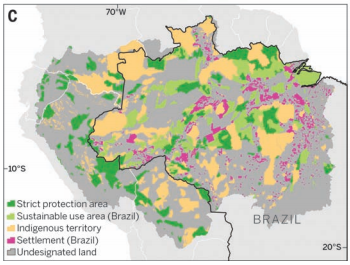

Conservation measures: Since 2002, Brazil has aggressively expanded its conservation programs, with more than 50 percent of the Brazilian Amazon now under some form of legal protection (see map).

Some of these areas are straightforward parks and wilderness areas. Other regions were handed over to indigenous peoples to manage. Studies have found that logging, rubber extraction, and other activities tend to be done more sustainably — and with fewer deforestation emissions — on indigenous peoples' reserves.

On top of that, the Brazilian government stepped up its enforcement efforts — including stricter monitoring of illegal logging. And, in 2008, Brazil began cutting off access to farm credit for those regions that had particularly high rates of deforestation.

International finance: Brazil has also received a fair bit of international aid for reducing deforestation. Norway has committed some $1 billion in financing under the REDD+ program to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions from forestry. Germany and the United Kingdom have also chipped in with aid.

Changes in the soy and beef industry: The Science paper, meanwhile, argues that shifts in the soybean and beef industry were particularly significant here. Between 1999 and 2004, a boom in soy prices had led to an acceleration in Brazilian farming — which, in turn, drove up deforestation rates rapidly.

By 2005, however, the business model was shifting (aided by a drop in soy profitability). Both the soy and beef industries come under heavy pressure from groups like Greenpeace, which put out a series of reports on the companies' culpability for deforestation.

In 2006, many of the world's largest soy buyers agreed only to buy soy that was grown on existing farmland — pushing the industry not to cut down any more forests to clear new land. A similar agreement for cattle followed a few years later.

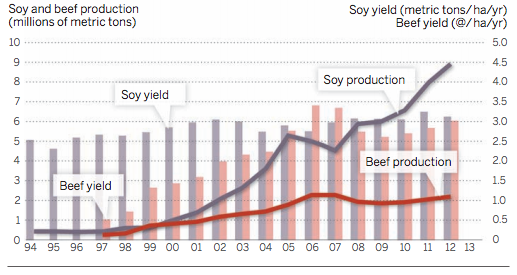

The result? Both the soy and beef industries were forced to find ways to use existing farmland more productively. And they did. Both soy and beef production have soared even though deforestation has dropped:

Beef and soy production have grown, deforestation hasn't

Nepstad et al 2014

The Science paper notes, for instance, that Brazil's soybean production soared 50 percent between 2006 and 2013 — but that increase occurred entirely on land that had already been cleared before 2006.

Still, it's not certain deforestation in Brazil will keep falling...

Aerial view of the Amazon Rainforest, near Manaus, the capital of the Brazilian state of Amazonas. Neil Palmer (CIAT)/Flickr

That all said, there's not guarantee that deforestation in Brazil will keep dropping — indeed, it appeared to tick up in 2013 and is likely to go up again in 2014.

Ultimately, farmland is a finite resource. If Brazil's soy and beef production is going to keep growing, then farmers and ranchers will either have to squeeze more out of their existing lands or cut down forests for new land. The Science paper suggests that beef yields could well keep rising and make further space for soybean crops — but this is far from certain.

There are lots of other variables at play here, too. How much outside pressure will soy purchasers and other companies face to distance themselves from deforestation? How strictly will the Brazilian government continue to crack down on clear-cutting? What sorts of incentives might convince farmers and ranchers to conserve forests rather than cut them down?

Despite the successes of the last decade, no one has the answers to all of these questions just yet.

...and rainforests are still dwindling outside of Brazil

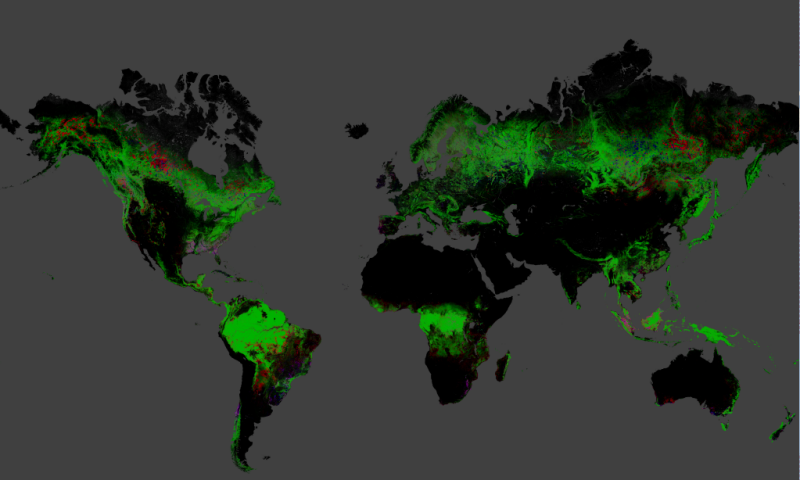

Change in global forest cover between 2000 and 2012. Green shows forest cover that hasn't changed at all. Black shows non-forest. Red shows forest loss. Blue shows forest gain. Magenta shows areas that are regrowing. Hansen et al 2013.

It's also worth emphasizing that Brazil is only one country. The drop in Brazilian deforestation since 2000 has been more than offset by increasing forest loss in Malaysia, Paraguay, Bolivia, Zambia, Angola and especially Indonesia.

That's according to a separate recent study in Science by a team of researchers from the University of Maryland, who used Google Maps technology to provide the most detailed maps yet of deforestation.

That team found, among other things, that the world had lost roughly 580,000 square miles of forest between 2000 and 2011 — an area the size of Western Europe.

And deforestation is currently increasing in the tropical regions. Here's a stark animation of what that looks like on the Indonesian island of Sumatra, which has lost half of its rainforest cover in the past three decades:

Unlike in Brazil, policies to halt deforestation in Indonesia have been woefully ineffective, the study found. After the government imposed a moratorium on new logging licenses in 2011, the rate of deforestation actually increased over the next two years.

Which is only to say that there are lot of underrated success stories on rainforests — and there's an excellent rundown of those stories in this Union of Concerned Scientists report. But the world is still far from ending tropical deforestation altogether.