Sacramento in July is among the sunniest places on the planet, averaging more than 14 hours of direct sunlight per day. On sweltering afternoons, when the grapevines are parched and the tupelo are drooping, the thermometer can spike to 113, and just about everyone turns on the air conditioner. These are the moments electric company officials dread, when sudden demand threatens to exceed capacity. But the local utility in Sacramento found a solution years ago, before the invention of Energy Star appliances and remotely monitored thermostats. It began giving away trees.

Shaded buildings use 25 to 40 percent less energy during the summer, averting power overloads. That's why, over the past two decades, the Sacramento Municipal Utility District has subsidized the planting of more than 500,000 trees—sycamores, lindens, maples, oaks and two dozen other varieties—making the city one of the leafiest in the western United States.

Sacramento was way ahead of its time. In most other U.S. cities, trees have been considered part luxury, part liability: expensive-to-maintain assets that interfere with power lines and clog sewer grates with dead leaves. At budget-cutting time, tree programs wilted.

Advocates knew intuitively the importance of trees, but had no way to prove it. Now, though, thanks to software tools developed by the U.S. Forest Service and studies by social scientists, there's no longer any need to wax poetic about the majestic beauty of urban greenery. The data tell the story: Trees are infrastructure. They cool the air, soak up climate change-inducing gases, protect against flooding, reduce people's stress levels and raise property values. Studies even show that shoppers spend more money at stores on tree-lined streets.

"Schools, police, fire, everything that we pay for from the tax structure has a direct value to it," says David Nowak, one of the creators of the U.S. Forest Service's tree-tracking software, called i-Tree. "So if you want to put trees on the same playing field to make economic decisions, we have to put it in economic terms."

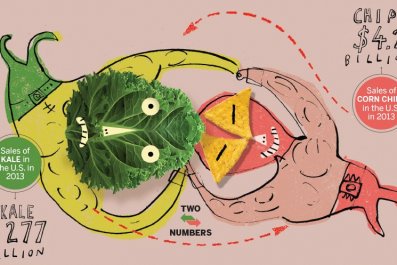

Each street tree in New York City provides $9.02 annually in air pollution reduction, $1.29 in carbon sequestration and $61 in storm-water abatement—$220 million in all, according to a 2007 study conducted with an early version of the software. Experts have calculated that Syracuse, N.Y., saves $1.1 million a year in health and related costs because of the soot its trees divert from the lungs of residents, and that the conversion of vacant lots to community gardens in Philadelphia hikes nearby home values by an average of $35,000.

In Los Angeles, Atlanta, Portland, Ore., and other cities, the data have convinced officials to enhance their urban forests. They are planting—New York and Philadelphia both aim to add a million trees—but they are also digging up sidewalks and laying soil over tar to create areas known as rain gardens and ecoroofs that absorb storm water. Seattle is transforming a seven-acre plot in the middle of the city into an "urban food forest" featuring apple, plum, pear and nut trees for public consumption.

The Quantification Quest

One sunny morning last July, Rich Hallett, a research ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service, darted into the middle of Madison Avenue in New York City, wearing black Carhartt work pants and a reflective orange vest. A line of taxis stopped at the red light faced him down like racehorses at a starting gate. Hallett ignored them, as well as the quizzical look he got from a tanned girl in a blue minidress crossing the street. Using a tape measure, he quickly confirmed that the GPS coordinate he sought was smack in the middle of the avenue, then headed back to safety on the sidewalk as traffic surged forward. Standing in front of a boutique called Comptoir des Cotonniers, where a handbag costs $450, Hallett made notations on a clipboard: not a single tree within this study area.

Less than an hour later, a song sparrow trilled as Hallett hiked into a woodland bordering train tracks along the Hudson River in the Bronx. Here, in a plot exactly the same size, amid discarded ice-cream wrappers and a pair of torn boxer shorts, he found 33 trees—many ailanthuses, a black cherry, a sapling elm, a young oak.

Hallett's team is conducting the newest systematic inventory of New York City's trees, collecting data to be crunched by the i-Tree software. Examining each of the city's 5.2 million trees would be cumbersome. Instead, using mapping tools, Hallett's team randomly generated 300 tenth-of-an-acre plots within city limits. They visited each site to painstakingly catalog the size, species and shade cover of every tree that was (or wasn't) growing within it. Extrapolating from that data, they will define the characteristics of New York City's entire urban forest. Randomness was key to making the study scientific—and it sent Hallett's team to some unlikely places. One site fell within the Freedom Tower construction zone, another on a landing strip at JFK Airport, still others within the property lines of suspicious New Yorkers. ("You're telling me they sent you to measure trees that aren't here?" one homeowner in the Rockaways in Queens remarked wryly. "OK, yup, that sounds like the government.")

Before i-Tree, it was nearly impossible to manage a city's forest—hard even to think of it as a single entity—because trees grow on private as well as public land. That made the work of the urban forester "like trying to manage a grocery store without knowing what's on your shelves," Nowak says. The app does more than count trees. It calculates the services the trees provide—benefits such as soaking up carbon dioxide that are becoming all the more valuable in this era of climate change.

Nerdy as it may seem, i-Tree can bring about tangible changes. In 2007, officials in Grand Rapids, Mich., decided to cut down 7,000 of the city's ash trees, including healthy ones, to stem the spread of a pest called the emerald ash borer. But a neighborhood group had just conducted an inventory and i-Tree analysis, and was able to show that each mature ash was worth more than $1,000 and provided $100 to $200 a year in benefits. With this new information, the city opted for the more expensive strategy of treating the largest at-risk trees with pesticides, a plan that no longer seemed extravagant.

It was a satisfying moment for Grand Rapids residents Carol Moore and Dotti Clune, longtime friends and community activists who had commissioned the study. It wasn't just that they had saved the ashes. They had helped people recognize the work trees do. "Trees are just not in people's consciousness," says Moore. "People learn photosynthesis in the fifth grade and never think about it again." This new awareness led Grand Rapids to launch, in 2012, a "tree of the year" award. The first recipient: a century-old ash almost four feet in diameter, valued at many thousands of dollars. It shades a huge swath of a busy commercial street and single-handedly absorbs nearly 7,000 gallons per year of excess storm water.

Leaf Therapy

That city trees survive and flourish despite multiple hardships—space constraints, poor soil, corrosive salt and chemicals—is not only an environmental boon. Trees are essential to city dwellers' health.

"People are starting to talk about trees, parks and gardens not just simply as beauty in the city but as a public health agenda," says Kathleen Wolf, a social scientist at the University of Washington's School of Environmental and Forest Sciences.

Fewer people die of asthma and heart disease in Chicago, Los Angeles and other U.S. cities because of trees' ability to absorb tiny soot particles known as particulate matter, according to a 2013 study by Nowak and colleagues. The team is now investigating the benefits trees provide by blocking the ultraviolet rays that contribute to skin cancers. Urban density magnifies the value of each tree: A single horse chestnut or maple cleans the air and provides shade for thousands of nearby residents.

Brief encounters with nature make people happier, reduce the chronic stress that leads to ill health and help both adults and children (including kids with attention deficit disorder) focus better on mentally taxing tasks, according to multiple studies. Patients, for example, who had window views of greenery required fewer painkillers.

Wilderness is not required. Even small patches of urban green—a reclaimed empty lot or neighborhood garden—can bring substantial benefits. The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society has been cleaning up trash-strewn vacant lots in inner-city Philadelphia, converting the spaces into inviting parks surrounded by folksy wooden fences. A 2011 study in the American Journal of Epidemiology found that in these neighborhoods vandalism and gun assaults decreased, along with residents' stress levels.

Rooted in the Community

After the devastation of the East Coast by Superstorm Sandy in October 2012, Erika Svendsen and Gillian Baine of the U.S. Forest Service NYC Urban Field Station began to research how New Yorkers use and vlaue open space. "We found that people are fiercely dedicated not just to their parks but to their trees," Svendsen says. "It could be a street tree; it could be a grove in a park. They'll even use words like 'This is mine, I care for it,' even though it is in the public realm."

Useful as the practical, dollars-and-cents calculations of urban planners are, they will never fully encompass the value of a tree that endures for years, stolid and reliable, becoming a constant in people's lives, a part of their history. One fall day soon after Sandy, Baine encountered a group of elderly men in Howard Beach, Queens, who were gathered around a willow at the water's edge. The men had carefully sandbagged the tree to protect it from the floodwaters, the way someone might shore up the basement of a house. They were fretting about the tree much the way they were worrying over their damaged neighborhood.

"Is this about that one tree or is it about these older folks coming together and their friendship?" Svendsen muses. "The tree becomes this marker of time and place, so it's terribly important and very much worth saving." Through the men's efforts, the tree survived. It's still there, and with any luck, will be for years to come.