When members of the House Financial Services Committee grilled Mary Jo White, the head of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), all they wanted to talk about was a book: Michael Lewis's Flash Boys.

"So you've heard all the stories in the paper, in the news," said Representative Scott Garrett, a Republican from New Jersey and chairman of the House Financial Services Subcommittee on Capital Markets and Government Sponsored Enterprises. "Can you tell us, Are the markets rigged?"

"The markets are not rigged," said White. "The markets—the U.S. markets are the strongest and most reliable in the world."

Garrett, whose responsibilities include oversight of the SEC, continued to press the matter, however. He asked White whether the fact that America's stock exchanges provide high-speed market data (which include the prices of Fortune 500 companies) to top-paying traders ahead of ordinary investors—a practice, he noted, "approved by the SEC"—constitutes "insider trading."

White's response: "I mean, if—if properly used, no."

The exchange between Garrett and White in late April was one of many awkward moments arising from what has become America's great "high-frequency trading" debate, in which the truth is often limited to the eye of the beholder (in many cases, the screaming beholder, judging by some of the recent shouting matches on CNBC).

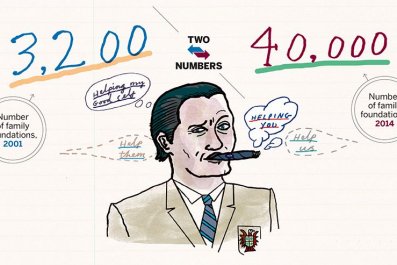

For as long as anyone can remember, market participants have clashed over how privileged market information is handled and who has access to what. This time it's different: A system of haves and have-nots is being effectively vouchsafed by one of Washington's key regulators overseeing what in 2014 is projected to be a $71 trillion market.

As White put it, "It is not unlawful insider trading." But against the backdrop of her agency's mission, "to protect investors, maintain fair, orderly and efficient markets," it may usher in the most awkward moment of all: the SEC finding itself pitted against other market regulators and members of Congress who believe U.S. markets are no longer fair.

High-frequency trading is a catchall term for the use of sophisticated technology, computing power and trading algorithms to transact a large number of market orders in milliseconds. The best-selling Flash Boys, out this spring, argues that the emergence of this type of trading, post-financial crisis, has made the U.S. markets less free and "more controlled by the big Wall Street banks."

So far, the U.S. Department of Justice and the FBI have stepped in to take a closer look at whether high-frequency traders and other market participants have unfair advantages in trading everything from stocks to futures to highly exotic derivatives. In addition, Newsweek has learned that since the New York state attorney general in recent weeks started subpoenaing trading firms, banks and exchanges across Wall Street, the SEC has refused to take a cooperative tack in its investigations.

While this would not be the first time tensions have flared between the SEC and the New York attorney general's office, it highlights how turf wars may be a complicating factor in remedying what ails the nation's markets. The SEC declined to discuss its talks with the AG, which has dubbed the edge it says is enjoyed by high-frequency traders as "Insider Trading 2.0."

Why does this matter? Because those who rely on America's markets for their livelihoods and retirement incomes, in addition to companies that depend on the nation's major exchanges to help them raise capital, grow their businesses and create jobs, are largely unaware that high-frequency traders and institutional investors are paying up to $180,000 a year to receive direct data feeds from exchanges that give them prices and crucial market information faster than the ordinary investor by roughly 15 to 20 minutes (not a typo).

"Bear in mind, $180K sounds like a lot to a normal person, but to people managing a large amount of money, it's not that much," said Rishi Narang, founding principal and quantitative investment manager at Los Angeles–based T2AM LLC and co-founder of high-frequency trading firm Tradeworx, which last year built and launched the SEC's data analytics system to track high-speed trading and fast-moving markets. "Advantages can always be decried as unfair. If people want to pay for better market access, shouldn't they be able to?"

For a fee, high-frequency trading firms also install their trading computers in the same data centers that house exchange trade-matching engines, benefiting from specially designed cable links and router configurations that allow them to receive, analyze and trade on exchanges' raw data feeds first.

The $180,000-a-year superfast feeds are "charged by the exchanges directly," Narang said, giving high-frequency traders prices and market data one millisecond ahead of Wall Street traders who use a slightly slower feed, the securities information processor (SIP), costing about $2,000 a year. The free feeds viewed by ordinary retail investors, depending on the security of the exchanges processing them, do typically lag by about 15 to 20 minutes, he said.

And, yes, this tiered system is perfectly legal. If you have the money, you can see up-to-date prices. If you don't, you cannot. Knowing the difference, of course, means those with access to real-time prices and other information can see where the market is heading before everyone else—and profit handsomely off that insight. In the meantime, investors relegated to the "current" prices available on websites like YahooFinance are actually receiving prices that are old. While the SIP feed has been around since before the decimalization and computerization of markets, the superfast feeds have existed for less than two years, T2AM's Narang said.

Adam Nunes, head of business development for New York–based high-frequency trading firm Hudson River Trading, says Wall Street traders paid for faster access to market data long before high-frequency traders entered the fray and started doing the same. "Everyone ignores that," he said, adding that "it turns out that there are direct feeds specifically for investors."

Now that high-speed traders have gained on the Wall Street establishment, those who cannot match their speed are crying foul. Nunes said the superfast feeds give high-speed traders a slight edge, but a lot of it has to do with the fact that their systems are fundamentally faster anyway.

"We wouldn't care if we got data alongside everyone else," Nunes says. "In fact, we trade in many markets around the world where there is no SIP feed and everyone uses direct feeds."

With trading now approaching the speed of light, the fact that market activity can no longer be seen by the naked eye is an aggravating factor in the regulation of markets, but the real concern is whether today's system of selling nonpublic information to the privileged few at the expense of everyone else threatens one of the bedrock principles of the nation's markets—they are, at least in theory, supposed to be free and fair.

"High-frequency traders are taking advantage of the ability to see where the market is moving before other investors can see or act on it," says Chad Johnson, head of New York's Investor Protection Bureau, in an interview with Newsweek. "We have exchanges that are pricing stock transactions based on a slower information feed that ordinary investors use and rely on, but selling to high-frequency traders a faster feed. If [they] are getting the fast feed, they're able to see the price of IBM is moving higher before the ordinary investor does."

He added, "They prefer trading at the exchanges that have a fast feed and a slow feed," because they can trade off the price differences and make money. "One is guaranteed to be a winner. And you can only win by making the rest of those in the market losers."

Another concern that has been raised is that high-frequency traders, in competing for rebates that exchanges often pay for people to transact in their markets, may crowd out orders that are more economical to investors, forcing investors to subsidize their activities.

Johnson's boss, New York State Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman, is taking a strong stance against what he contends are traders who have been allowed to game the nation's increasingly fragmented and decentralized market system. "Armed with what amounts to knowledge of the future, these traders execute tens of thousands of trades in milliseconds with essentially zero risk, driving up the cost for other purchasers of stock," he said in a statement to Newsweek.

Taking issue with that is the SEC's White, who in her testimony to the House Financial Services Committee said exchanges under her purview are required to provide all data feeds at the same time. "That doesn't answer the question how fast [the feeds] can be used and absorbed, obviously," she said. Some traders simply have better, faster technology than others.

The SEC has rejected the idea of imposing speed limits on trading and data feeds, saying such a move would be backward-looking and only make markets less efficient. Still, with the SEC under pressure from other agencies, some expect it to become more vigilant.

"We have a number of investigations underway related to high-frequency and automated trading, including investigations involving potential abuses of order types, market manipulation schemes and potential abuses at different types of trading venues," says Andrew Ceresney, SEC Enforcement Division director.

A source familiar with the SEC's thinking who asked not to be named said the SEC "is looking in the rear-view mirror, and they see the attorney general's office, and they also fear the courts.

"But it also fears doing something rash and being told it's made an even bigger mess of things. Remember, it was the SEC that, several years ago, blessed the market's fragmentation in the first place. Many of the issues in Flash Boys are absolutely true, and everybody in the industry knows it. It definitely put market regulators under the gun, and they're feeling defensive because now they look bad in the public eye."

On the sidelines of the Milken Institute Global Conference in Beverly Hills, California, in late April, Terry Duffy, chairman of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CEM), the world's largest futures market, said he felt it was best to leave the policing up to Washington's regulators. (The futures market is regulated not by the SEC but by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which has tried and failed for years just to come up with a definition for high-frequency trading.)

"If, in fact, customers are getting front-run by [high-frequency traders] or anybody else, that is against the law and should be penalized," Duffy said. "Those people should not be participating in the marketplace, so I am hopeful that's not going on. But if it is, the government agencies can deal with it."

In congressional testimony last week, Duffy stated that his exchange offers "a level playing field," although traders "have several options in terms of how they can receive data from us." He did not elaborate. A class-action lawsuit filed by a group of Chicago traders alleges that since 2007, the CME gave high-frequency traders a sneak preview of prices before other market participants, an accusation the exchange vehemently denies.

Until this month, no exchange boss had dared break the silence and say that something might not be quite right. That is, until Jeff Sprecher piped up—the chairman of Atlanta's IntercontinentalExchange Group, which presides over both futures and derivatives markets, as well as the New York Stock Exchange, which it bought late last year.

"Our market structure might have created a better pie with lower exchange fees and tighter spreads, but it is a shrinking pie that fewer want to consume," he lamented during an investor conference call, saying an industrywide effort would be needed to resolve it. "What's saddening about the U.S. equity market is that when I go out and talk to my friends, they do not have confidence in those markets."

Perhaps with the idea that the issues may be disentangled most ably by those who know them best, the SEC has begun to hire former high-frequency traders, financial engineers and Ivy League Ph.D.s, said T2AM's Narang.

"This is a hyperdimensional space, and the number of things that are happening and that you can do and think about in it is fairly limitless," he said. "We've come a long way, but to get God's understanding of the market is going to take more time."