In the next 24 hours, the world will guzzle 1.6 billion cups of coffee, the most popular beverage on the planet besides water and tea. It’s big business, too: Global coffee exports totaled $28.6 billion in 2013—after oil, it is the world’s most traded commodity.

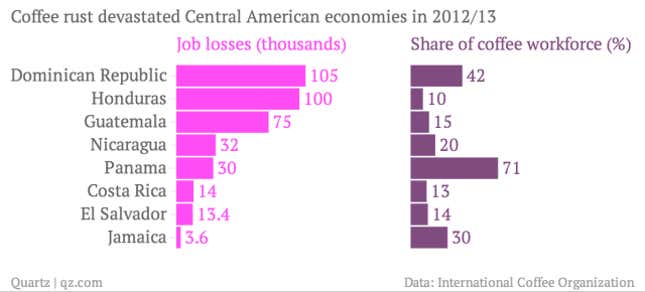

But there’s something else that likes coffee even more than humans: Hemileia vastatrix, better known as coffee rust or roya disease. It’s a fungal parasite that survives on coffee tree leaves, and in the 2012-13 crop year alone, it caused nearly $499 million in losses (pdf, p.3) among Central American coffee growers.

Worse, big swings in weather resulting from climate change are hastening the spread of this fungus, reports National Geographic, and causing epic droughts on plantations elsewhere in the region. The devastating double-whammy of climate and disease could wipe out as much as two-fifths of Central America’s coffee crop.

Most likely originating in East Africa, coffee rust infects the leaves of the coffee plant, speckling them with pale yellow spots that scramble photosynthesis, leaving the plant unable to breathe. The fungus first arrived in the Western Hemisphere in the 1970s, when it suffocated more than half of Central America’s crops, spreading both by wind and on the clothes of migrant workers.

Scientists eventually came up with rust-resistant coffee species. But those commercial crops are stuck with a limited range of genes, while rust keeps evolving, expanding its range. In evolutionary terms, the coffee plants can’t keep up.

And in 2010, rust bounced back in a more aggressive form, this time in Guatemala and Colombia. By 2013, the fungus infected three-quarters of El Salvador’s crops, and more than two-thirds of Guatemala’s and Costa Rica’s. Not only Guatemala, but Honduras and Costa Rica have since declared national emergencies to free up funds for pesticides.

One reason for the fungus’ return is that rust spores need a lot of moisture to grow—around a day or two of continuous rain or heavy dew. While those conditions normally exist only during the rainy season, climate variation—the term for dramatic changes in weather that have intensified in recent years—means downpours are happening more frequently. Tellingly, 2010 was an unusually wet year in Central America (pdf, p.8). Climate variation is also responsible for the drought that’s devastated the coffee crop of Brazil, one of the world’s biggest suppliers.

Weird weather isn’t the only problem tethered to climate change; so is global warming. Hotter temperatures are a particular menace to Arabica, a type of coffee that makes up seven-tenths of global coffee production and requires cool climes to grow. A recent study predicted that by 2080, global warming would make two-thirds of current farms too hot to grow Arabica—and that is the best-case scenario.

Warmer weather is also allowing rust to attack at higher altitudes, and is accelerating the spread of a slew of other coffee parasites. For instance, research in Ethiopia, the cradle of coffee civilization, found that an insect called the coffee berry borer struggled to reproduce in low temperatures. Once things warmed up, the borers could be grandparents within a year.

This is bad not only for global caffeination but also for small Central American farmers, millions of whom depend on coffee for their livelihoods. In Guatemala alone, the blight robbed coffee farmers of up to three-fifths of their income in 2013.