Cyber insecurity: When 95% isn’t good enough

Simply sign up to the Cyber Security myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Two weeks after hackers broke into Sony Pictures’ computer systems, deleting important company files and exposing embarrassing emails, technology experts at some of the world’s largest financial institutions decided to run an experiment.

They took copies of the “malware” — malicious strands of computer code — used in the Sony attack and watched what it would do if it were unleashed in their own computer systems.

The Sony hack was a sophisticated piece of work. Like a revolver, the malware shot off a round of code in search of a vulnerability in the network. If that potential weakness had been properly patched by the bank’s tech team, it would trigger another round and go off in search for a different vulnerability. This could go on for seven or eight rounds, according to a bank official.

The results were unnerving. Before seeing the Sony malware at work, a top security officer at a major US bank said he felt successful if he had 95 per cent of his network’s vulnerabilities covered. “That five per cent I’m not sure I’m satisfied with anymore based on what we learned out of Sony,” the official said.

Following the exercise, he says, he was able to convince the bank’s top executives to pump cash into plugging the holes — a job that became its number one security priority.

We’re taking “a fighter’s stance”, says the security officer. “We’re not going to wait to be hit.”

After a wave of increasingly sophisticated cyber attacks, corporations of all types — from entertainment groups like Sony to retailers, insurers and even carmakers — are spending big money to fight back against hackers. But the financial industry is the most frequent target, facing 300 per cent more cyber attacks than any other sector, according to a report from Websense, a cyber security company. Regulators have noted that cyber attacks on banks are an emerging threat that could pose a systemic risk to the sector, according to a May report by the US Financial Stability Oversight Council.

The banking industry has poured hundreds of millions of dollars into securing its networks. They have hired thousands of the brightest tech minds, plucking former intelligence officials from spy agencies and combing the networks of the Chaos Computer Club, Europe’s largest association of hackers, for recruits.

Besides the obvious financial incentives for hacking banks, the sophistication of their security makes them a tempting target. The Financial Times interviewed top security officers at some of the world’s largest banks, but none would speak on the record for fear of prompting reprisals from hackers.

And yet serious breaches happen. An attack on JPMorgan Chase exposed contact information of 76m US households in 2014 — a year when even it spent more than $250m and had about 1,000 people focused on cyber security. To the bank’s embarrassment, hackers were able to penetrate its network because there was no requirement for two-step verification — a procedure used by many free online services such as Gmail.

The bank said no account information, such as user names and passwords, was taken during the breach. Still, it shook customers’ confidence in a system that holds personal financial information about their mortgages, savings and bank accounts.

Banks exist to safeguard money and data, but the risks they face if their systems are breached are not just reputational. They are also responsible for the cost customers incur following a hack of their own networks or those of others — including retailers, who have become frequent targets of criminal groups. The 2013 breach of Target, the US retailer, is estimated to have cost banks more than $200m. Lloyd’s, the UK insurer, has estimated cyber attacks cost all businesses as much as $400bn a year.

The cost of breaches on the financial sector are going up, with the number of companies reporting losses of between $10m to $20m because of hacks going up by 141 per cent in 2014 compared with the previous year, according to PwC. The average number of detected incidents rose from 4,628 in 2013 to almost 5,000 last year.

Unlike other industries, the financial sector is required by US law to protect customer information. US bank regulators have overseen their information technology since 1978, and regulators have been required to issue security standards to safeguard customer information since 1999. Increasingly other regulators — in the US and around the world — have added cyber security to their reviews. A security officer at a large European bank says that in the past 12 months his company has received 70 requests from regulators related to cyber security, with some questionnaires exceeding 300 queries.

The economics of hacking

After a series of high-profile attacks, many companies are considering more aggressive tactics to fight back against cyber crime, including “active defence” strategies. The most controversial is “hacking back” against cyber criminals, which is against US law and, according to several bank officials, a bad idea because of the difficulty in definitively identifying culprits. Instead, they are fighting back by bolstering their networks, establishing “fusion centres” that serve as a sort of central command, and creating malware laboratories to try to keep pace with the hackers.

“It’s not enough to build up walls and harden the systems, you need human capital to understand the threat,” says Austin Berglas, the former deputy chief of the New York FBI’s cyber security unit who is now at K2 Intelligence.

The banks created a trade group, the Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center, or FS-ISAC, in 1999 to share information about security threats. It has 5,500 members, including JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, Wells Fargo and HSBC.

Podcast

Cyber Insecurity: The fight back

Are hackers winning the battle for cyber security? FT West Coast editor Richard Waters speaks with San Francisco correspondent Hannah Kuchler and investigations correspondent Kara Scannell to discuss how banks, companies and governments are finding ways to marshal their defences.

The industry has also created a cyber-attack alert system with the Depository Trust & Clearing Corp, a clearinghouse that processes trillions of dollars in securities transactions for more than 50 US exchanges and trading platforms. Together they created Soltra Edge, software designed to give users timely information in standardised language about potential attacks. There have been about 1,800 installations of the Soltra Edge since it was rolled out in December 2014. “If we don’t protect ourselves, nobody else will,” says Bill Nelson, head of FS-ISAC.

The Soltra system is designed to undermine the economics of hacking. Hackers often use the same tactics to target multiple victims, driving down the cost of an attack while expanding the potential rewards. Soltra, also used by healthcare companies and retailers, is meant to prevent hackers from using the same method for multiple breaches, driving up their costs.

“If an attack that had cost $1,000 now costs $50,000, maybe a hacker will think twice,” says Mark Clancy, who just stepped down as chief information security officer at DTCC to be chief executive of Soltra.

Mr Clancy remembers when he and his fellow data security experts in the financial industry commiserated about how their employers did not understand what they were dealing with. “The security teams were enforcing regulations for a problem nobody understood or heard about,” says Mr Clancy, who left Citi in 2009. “Maybe we did a poor job of articulating the risks. But people obviously get it now.”

Bank officials began to wake up to the risks after Nasdaq and Citi were hacked in 2011. That February Nasdaq said its computer systems — but not its core trading platform — were penetrated by hackers. Four months later Citi’s online credit card website was hacked and 360,000 of its customers’ account details were accessed. The next year, most major banks suffered an onslaught of “denial of service” attacks, which US officials suspect had ties to Iran.

Starts with a malicious email

The problem many global financial institutions have is old and incompatible technology that was taped together as the result of mergers. Others have trading platforms that are not easily or cheaply transferred on to new systems.

“Our measure of success is eliminating legacy [technology] and getting on to a new defended environment as quickly as we can,” says a security officer at a global investment bank. “The question for us and other large banks is, how do you get your entire environment on to that in a way that still serves customers?”

“I’d like to wave the magic wand and have it happen now,” he says. “We’ve done a lot and there is still a way to go.”

Many large banks have begun moving their technology on to a “defensible architecture”. Some are building new platforms, setting up clouds, and creating virtual desktops to keep data away from the “perimeter” and locked into servers that make it inaccessible to USB drives — the small storage devices Edward Snowden used to steal data from the National Security Agency.

“Ninety per cent of the bad activities start with an email that comes into one of your employees that has a malicious code in it and they open it. It just happens,” says a security official who ran the Sony malware experiment.

But security restrictions often bog down business functions. One security officer said some traders objected to extra steps they thought slowed down their business decisions.

Big problems for small banks

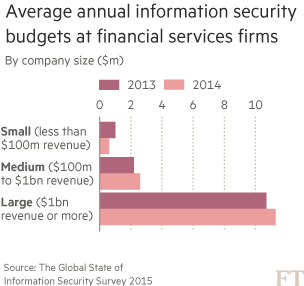

Investing in more secure technology is expensive for the global banks, but for their small and midsized peers it is prohibitive. This leaves them potentially at greater risk and ill-equipped to deal with the threat, bank advisers say.

For some, the best defence is to simplify their systems. When Grand Rapids State Bank, in Minnesota, acquired Crow River State Bank last year one of the first things it did was move the new company on to its computer network.

“The number one thing on the list,” says Noah Wilcox, president of Grand Rapids, “was to effectively strip the entire network out of the organisation and implement a new network that is consistent with the kinds of security that we require of ourselves.”

Grand Rapids, a founding member of the FS-ISAC, has assets of $320m, employs a three-person security team and relies on outside vendors for additional security.

“It’s not always about loans and deposits,” says Mr Wilcox. “It’s how you deal with the data you’re entrusted by the public to protect.”

He would like smaller banks to have the same access to classified information as the large ones. And would also like to see the government, which has been hacked many times, better protect itself. “They’re full of ‘do as I say not as I do’. They are telling everybody else this is how you should do it but they’re not taking their own medicine.”

Bank regulators have their own challenges. Since the financial crisis, regulators have overhauled the way they monitor and assess Wall Street. But their approach to cyber crime shows they still have work to do in breaking down barriers to allow them to spot hacking trends across the industry. Right now, they only focus on incidents at individual financial institutions, the Government Accountability Office said in a report this month.

“Regulators were not routinely collecting IT security incident reports and examination deficiencies and classifying them by category of deficiency,” the GAO said.

Banks complain that they need more usable cyber threat information from regulators. “One institution’s representative said that receiving insufficiently detailed information was similar to telling the institution that it might be attacked by a criminal in a red hat,” said the GAO, referring to the vague information banks receive.

FT Series

Devastating cyber attacks are on the rise, putting vast amounts of personal and business data at risk. FT examines how banks, companies and governments are trying to mount a concerted fightback against the hackers

The US Treasury has recently made a push to make sensitive but unclassified information available more quickly, while also urging law enforcement to allow classified information to be shared more freely with banks.

“There are miles and miles to go on that front,” Mr Clancy says of the Treasury’s initiative. “But we are starting to see fruit out of that effort.”

There is also frustration with the US government’s response to breaches, including the hack of the Office of Personnel Management, which exposed background checks on 22m current and former government employees.

“If somebody broke into OPM and walked down the hallway and stole all that data we’d have a national manhunt to try to find these people. For some reason we feel differently about a cyber event because you can’t touch it,” one US bank security official says.

On the front lines, the best security may be constant vigilance. Last month, the official who duplicated the Sony hack piped the malware through his system again. This time he felt better about the result.

“We went back into our playbook and said, we have to understand destructive malware. We’ve taken lots of hours with the team to think through how do you do that,” he says. “Then we exercised it and felt good about it.”

But he adds: “I still have to do my war games, update our playbooks, rehearse and practice.”

Comments