The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet is on its way to becoming one of the biggest numbers in economics.

Sure it’s not Japan’s ¥1 quadrillion government debt. Or the US economy’s $16 trillion-plus economy. (Or come to think of it, the US’s $16 trillion-plus debt.)

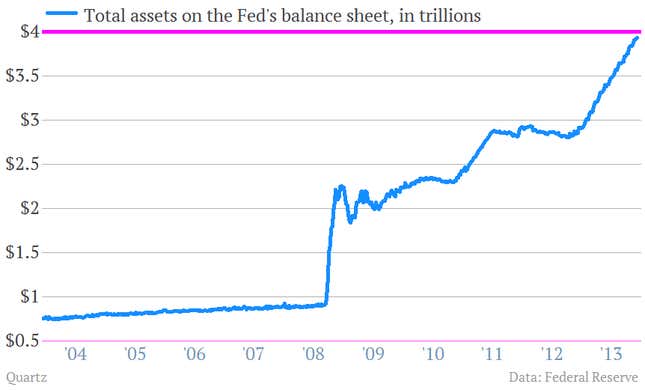

But still, the amount of financial assets the US central bank is holding in the wake of quantitative easing and other stimulus measures of the past five years is a very big number: Unless something truly bizarre happens, it will hit $4 trillion very soon. In fact, it’s basically already there. A weekly update yesterday afternoon put its size at $3.994 trillion.

What does this mean?

In short: A $4 trillion Fed balance sheet is basically just another way of acknowledging the fact that, since the financial crisis hit, the US central bank has been trying every trick in the central banking playbook to try to help the US economy.

But what is a balance sheet?

A balance sheet is basically snapshot in time that tells you what a business owns—its assets—and what it owes other people, its liabilities. On a balance sheet, assets always have to equal liabilities, so the “size of the balance sheet” technically refers to both sides. But for the most part people are really interested in the asset side.

What does the Fed own?

While a lot of people would have you believe that the Fed’s bond-buying binge is a radical new instance of the Fed meddling in the markets, it’s not. The Fed always meddles in markets. And the way it does that is by buying assets.

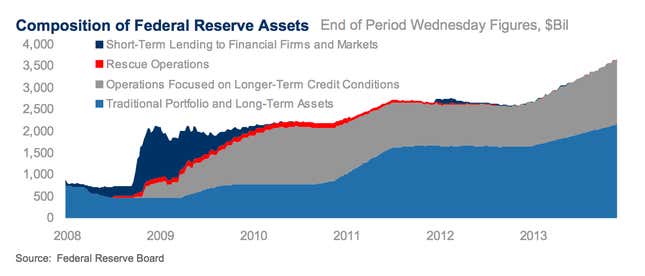

It’s true that for much of its history the Fed has only bought a very limited subset of stuff, mostly short-term Treasury bills issued by the US government. During the 2008 financial panic, the Fed did a whole bunch of unusual things like buying rotten batches of mortgage bonds from collapsing institutions like Bear Stearns and AIG. But such rescue-operation assets have long since shrunk as a share of assets on the balance sheet. (That’s the red bit in the chart below.)

But the Fed has kept doing some other unusual things it took up during the crisis. For instance, it’s still buying the packages of bonds where nearly all US mortgage loans end up, in an effort try to keep mortgage rates low. It’s also buying longer-term Treasury bonds. (It once bought only the really short-term ones.) The idea is that by purchasing those financial assets, it will push interest rates lower and make it cheaper and more enticing to borrow.

What does the Fed owe?

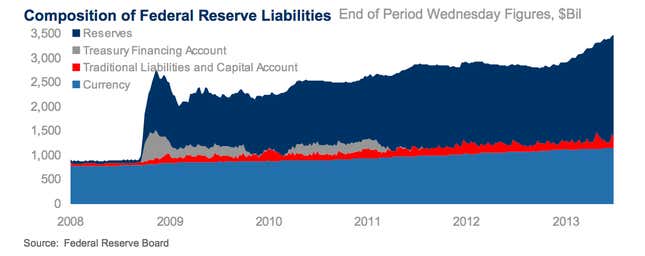

Well, the Fed is a bank that owes money to the entities who’ve made deposits. (Since the Fed is a bank for banks, the deposits are reserves that banks leave at the Fed.) You can see from the chart below that those reserves have ballooned since the crisis hit. That’s because the Fed has been buying its bonds from the banks, and the payments for those bonds go into the banks’ reserve accounts at the Fed. (Incidentally the other main liability the Fed has are Federal Reserve notes—dollar bills floating around as currency.)

Where does the Fed get the money to pay for those bonds?

The hard truth is that the Fed actually just creates it out of thin air. When it buys a bond from a bank, it just electronically credits the bank’s account at the Fed with the reserves.

How can that be?

It’s just the way it is.

How can I go on?

You’ll find a way.

But if the Fed keeps creating money out of thin air, won’t we soon have a kind of situation where money has no value at all and people will be running around shirtless in the streets demanding blood?

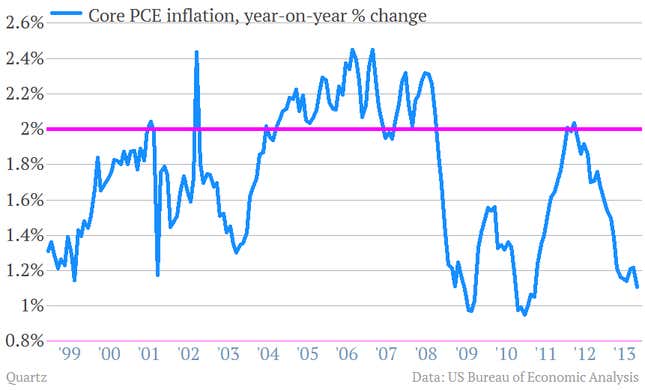

Well that’s what some people say. They’re called monetarists. And they’ve been warning that the Fed’s bond-buying programs would lead to a really scary inflationary spiral any second.

Has it happened?

No. Inflation is well below the Fed’s long-run target of 2%.

Why hasn’t the US turned into Weimar Germany?

There are a bunch of reasons. But the main thing to keep in mind is that the reserves that the Fed uses to pay for the bonds it buys from banks aren’t really money. They’re pretty close to money. But they don’t become money until they move out of the Federal Reserve system and into the real economy.

How do they move out?

Reserves become money once banks lend them to consumers and business owners in the real economy. But since the financial crisis hit, banks have been pretty conservative lenders. (It makes sense: Not only did the entire system nearly collapse because of reckless lending a few years ago, the economy was also terrible.)

So if banks aren’t lending reserves, did the Fed’s bond buying program do any good?

Yes, the Fed was able to do some good things. For example, it pushed mortgage rates down to record lows, which helped make it easier for people to refinance. But the programs weren’t a panacea for the economy as a whole.

Ok, fine. But now the Fed owns a ton of bonds. And I just read that the bond market had a bad year. If bond prices fall sharply won’t the Fed be exposed to losses?

That’s a very complicated question. And if the Fed were a regular bank—which has to take losses or gains on its portfolio investments depending on what the market does—you’d be right. But it’s not a regular bank. Under the accounting rules the Fed follows, the central bank doesn’t have to take a loss on bonds it owns if the market falls sharply. Now if the Fed had to sell its large stockpile of securities at a loss it would have to recognize those losses. But it doesn’t have to. And increasingly, it looks like it never will.

So a $4 trillion balance sheet isn’t a problem?

There is one problem: The Federal Reserve is a creature of the US Congress. And as the balance sheet gets bigger and bigger, it’s been an easy area for opponents of the Fed to spotlight. After all, if what the Fed was doing was so effective, why does it have this ridiculously large balance sheet? In theory, a Congress worked up about the size of the Fed’s balance sheet could take steps to take away some of the Fed’s independence through legislative action. (That’s every Fed chairman’s worst nightmare.) So if there is a problem with a large balance sheet, it’s more political than financial.