Investing: The index factor

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It seemed a mundane statement. MSCI, the New York-based index provider that runs the most widely accepted benchmarks of the emerging markets, had decided against a proposal to add China’s domestic A-shares to its main indices.

The company explained that China had still not shown that A-shares — open to non-Chinese only through a steadily expanding quota system — were sufficiently available to overseas investors. It also announced a joint working group with the China Securities Regulatory Commission with a view to adding A-shares by 2017. This innocuous sounding announcement turned out to be one of the catalysts for the huge sell-off in the Chinese stock market that sparked alarm around the world. It also offers a dramatic demonstration of the rising influence of the index.

Indices and the companies that calculate them have grown so powerful that they do not just track markets, but move them. With some critics contending that they help to inflate investment bubbles, the role that indexers play is facing closer scrutiny from regulators.

MSCI’s decision on China mattered because some $1.7tn in global assets are benchmarked against its emerging markets index, making it the dominant benchmark of the sector. None of that is in A-shares. Even MSCI’s modest proposal to admit A-shares to the index at only 5 per cent of their total market value would have forced investment managers to switch at least $20bn into A-shares. Any subsequent decision to admit A-shares at their full market value could mean as much as $400bn at current values switching from other emerging nations such as South Korea or Brazil into China’s internal market.

In these circumstances, any decision MSCI took would inevitably move the market. This raises the ire of critics.

According to George Cooper, a fund manager and author of The Origin of Financial Crises, “the big beef” involved in tracking an index is that “you mechanically lend most to the biggest borrowers, and buy the most overinflated stocks”. He draws an analogy with road safety: “Imagine a motorway where cars all benchmark their speed to everyone else. Then imagine what happens if everyone is trying to be a little faster than everyone else. They end up crashing.”

Perverse incentives

Paul Woolley, head of the London School of Economics’ Centre for the Study of Capital Market Dysfunctionality, suggests that market benchmarks inflate bubbles and should be abandoned altogether, in favour of comparing fund managers to rises or falls in gross domestic product. “When used as benchmarks for active management, market cap indices carry perverse incentives that impair fund returns, distort prices and make them an inefficient basis for passive investment,” he says.

Index providers themselves strongly disagree. “It’s a theoretically valid concern but we are very, very far from it being structural,” says Baer Pettit, MSCI’s head of index strategy. “The 1929 and 1999 bubbles weren’t about indexation. Neither was the tulip bubble [of 1637]. I’d love to see empirical evidence that validates that point. There isn’t a lot of it.”

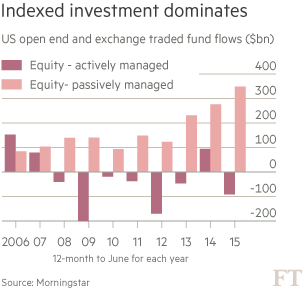

Indexers’ power derives partly from the growing number of funds managed “passively” to follow an index. Indices provide the basis for futures markets and for exchange traded funds — that by design must directly track indices. ETFs were introduced only 25 years ago but now manage more than $3tn globally.

But active managers, who merely use the MSCI index as a benchmark, would also have been obliged to buy A-shares. They know that big pension fund managers and their consultants will decide whether to allocate them money based on their performance compared with the MSCI benchmark. Not buying A-shares would have been too great a career risk.

Not only are the indexers powerful, but that power is concentrated in a few hands. Consolidation has left three big companies — S&P Dow Jones, FTSE Russell and MSCI — jointly providing the benchmarks for 73 per cent of US mutual fund assets, worth some $9.4tn. In bonds, the indices overseen by Barclays are dominant. Its bond aggregates (formerly known as the Lehman Aggregates) account for more than half of all ETF assets held in fixed income.

Indexing has become a big business. In the case of the world’s largest ETF, the $177bn SPDR, which tracks the S&P 500, S&P Dow Jones receives a licence fee of a little over 0.03 per cent of assets, currently equivalent to more than $50m a year.

Yet despite their power, indexers are little understood. James Breech, who runs Cougar Global Investments, a Canadian firm that allocates money to index-tracking exchange traded funds for wealthy clients, offers this confession: “When we tell our clients that we look at index construction, they say they never thought about it. Even advisers don’t pay attention. End investors have no idea whatever.”

This is a recent phenomenon. Fifty years ago, indices were simple averages produced by newspapers and academics using slide rules, to help gauge the general direction of the market. They covered only stocks. The FT-30 or the Dow Jones Industrial Average provided a crude guide to how the market was performing, and investment managers did not pay them close attention.

Now, computerisation has revolutionised them. With benchmarks for stocks, bonds, commodities, real estate and many other assets, there are far more indices in the world than there are stocks. S&P Dow Jones, the biggest indexing company, alone calculates more than 1m indices each day.

According to Mr Pettit: “The rise of indexation over the past 15 years, as it strengthens trends in markets towards transparency, is a good thing for savers and investors. There has been a huge rise in the quality of financial information systems from 1980 to 2000.”

Alex Matturri, chief executive of S&P Dow Jones Indices, says: “Why do we calculate a million indices every night? Because there’s a demand for that.”

With so much at stake, providers have to avoid conflicts of interest — particularly in bonds, where the main indices are controlled by banks, who themselves have businesses issuing bonds. In the wake of the Libor scandal, in which traders manipulated a benchmark for their own profit, banks are aware that bond indices could open them to legal risks. Barclays has been exploring a sale of its index business — for a price tag that could exceed $1bn — since last year.

Even if banks’ indices do not change hands, independent operators believe there is room in the market for them. “Our job is to capture market share,” says S&P’s Mr Matturri. “I think we can. Three years ago it was hard to launch fixed income indices. Post the Libor scandal, people understand the conflicts in the business when you aren’t an independent provider.”

Indexers go out of their way to use their power responsibly, as MSCI demonstrated with a long and transparent consultation before making its decision on China’s A-shares. Their rules are published and transparent, overseen by boards that include big investors. The major indexers themselves have no vested interest in whether an index goes up or down.

Mark Makepeace, CEO of FTSE Russell, contends that the power truly belongs with indexers’ ultimate clients, the big investing institutions such as BlackRock and Vanguard. “If we do a rule change, we have to consult with the institutions. The power is with them. We only make changes with their support. They do have the ability to choose between us and MSCI.”

However, index providers do have the final say over which stocks, bonds or countries go into which index. And once an index becomes dominant, more or less any change, however it is organised, will move the market.

Transparency

For example, Russell indices follow very transparent rules, meaning that alert investors can calculate in advance which stocks will be moving in and out of its indices on the day each June when its indices are reshuffled.

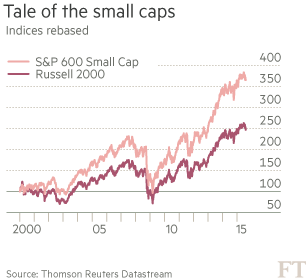

This is almost always the busiest US trading day each year. This year, Nicholas Colas of Convergex in New York calculated that, from the start of May, the 120 stocks to be added to the Russell 2000 index of smaller companies gained 11 per cent, while those being deleted fell 2 per cent and those facing promotion to the less widely tracked Russell 1000 index of larger stocks barely moved. The transparency warped and changed the market outcome.

But the alternative, of leaving some discretion, also has drawbacks. S&P fills vacancies in its S&P 500 index of big US companies whenever they arise, usually through mergers. It attempts to maintain a balance between sectors and to avoid companies that have not yet built a history of trading profitably. This gives its committee some discretion, and frequently creates controversy. Facebook and Google were already huge companies when they joined. The stocks it adds invariably rise sharply on the announcement — annoying fund managers who say this makes the index prohibitively hard to beat, just as the Russell’s transparency makes it easy to beat.

How deeply the indices warp markets remains hotly disputed. Most bond indices are weighted according to how much debt a company or country has issued. This means that the more indebted an issuer becomes, the bigger share it will take in the index, and the more of its debt passive funds will be required to buy. This is why many funds were led to load up on Argentine debt before its default crisis.

But there are also concerns about the use of indexing in equities. Most indices are weighted according to market capitalisation. That means the more a company’s price grows, the more index-trackers will be required to buy of it, opening them up to accusations that they help to inflate bubbles.

A second charge is that indexing attacks market efficiency. The more money passively tracking indices, the less devoted to seeking out underpriced stocks. If all money were managed passively, markets would cease to function.

Dave Gedeon, managing director of Nasdaq indices, suggests there are natural counterweights. “The more money tracks passive, the more opportunity there is for active managers who can demonstrate value. They should be able to find more opportunities in certain assets,” he says.

A final concern is that indices alter perceptions. The growing field of behavioural finance — applying insights from behavioural psychology — suggests this could create anomalies. For example, fund managers now generally refer to themselves as being “overweight” in a stock, rather than saying that they own it, showing that their thinking is dominated and framed by their index. With so few providers now dominating the market, Peter Atwater, of Financial Insyghts, a US consultancy, suggests there is “an oligopoly of confidence”.

This matters because subtle differences in methodology lead to huge differences in outcomes and perceptions. The three most widely followed indices of commodities give a radically different picture (see above) of how raw materials prices have performed since the crisis, largely because they give very different weights to oil.

Beating the index

Within equities, Mr Breech points out big differences between the Russell 2000 and the S&P 600, two rival indices of US smaller companies. The Russell is based solely on market value, and is of great interest to academics; but the S&P tends to perform better, because it requires that companies have a record of making profits before it includes them, and because it sets a much higher standard for liquidity. “We always used the Russell 2000 as our small-cap index, but then I realised that people like it because it’s easy to beat. If you’re an institution you’d rather have a benchmark that’s easy to beat. For us, an ETF is a means of access to securities. We care what we own and we want profitable companies.”

When indices were merely used as general measuring sticks, such issues did not matter. Now that they are the building blocks for multibillion-dollar products, they matter a lot.

Yet most investors remain blissfully ignorant of this. Nick Smithie, chief investment strategist at Global Advisors, a small New York-based ETF provider that creates its own indices, puts it this way: “We never get asked about the brand of index we are using. Nobody ever says, if that’s not an S&P index we won’t buy it, or anything like that.”

If such thinking takes wider hold, the big index providers might yet be displaced. For now, they remain among the most powerful, if least heralded, players on the financial markets.

Letter in response to this article:

Indexation, bubbles and circumstantial evidence / From Stephen Swift

Comments