The Myth of the Barter Economy

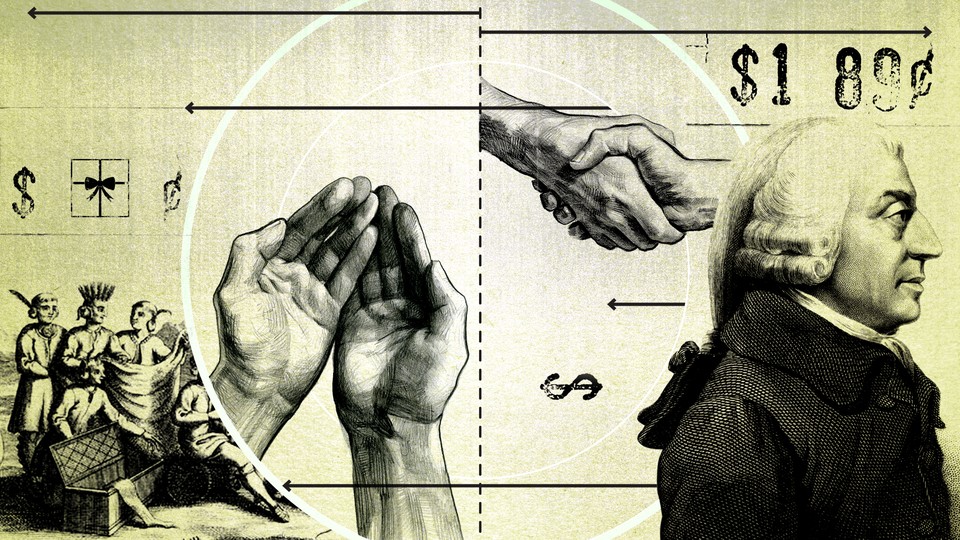

Adam Smith said that quid-pro-quo exchange systems preceded economies based on currency, but there’s no evidence that he was right.

Imagine life before money. Say, you made bread but you needed meat.

But what if the town butcher didn’t want your bread? You’d have to find someone who did, trading until you eventually got some meat.

You can see how this gets incredibly complicated and inefficient, which is why humans invented money: to make it easier to exchange goods. Right?

This historical world of barter sounds quite inconvenient. It also may be completely made up.

The man who arguably founded modern economic theory, the 18th-century Scottish philosopher Adam Smith, popularized the idea that barter was a precursor to money. In The Wealth of Nations, he describes an imaginary scenario in which a baker living before the invention of money wanted a butcher’s meat but had nothing the butcher wanted.“No exchange can, in this case, be made between them,” Smith wrote.

This sort of scenario was so undesirable that societies must have created money to facilitate trade, argues Smith. Aristotle had similar ideas, and they’re by now a fixture in just about every introductory economics textbook. “In simple, early economies, people engaged in barter,” reads one. (“The American Indian with a pony to dispose of had to wait until he met another Indian who wanted a pony and at the same time was able and willing to give for it a blanket or other commodity that he himself desired,” read an earlier one.)

But various anthropologists have pointed out that this barter economy has never been witnessed as researchers have traveled to undeveloped parts of the globe. “No example of a barter economy, pure and simple, has ever been described, let alone the emergence from it of money,” wrote the Cambridge anthropology professor Caroline Humphrey in a 1985 paper. “All available ethnography suggests that there never has been such a thing.”

Humphrey isn’t alone. Other academics, including the French sociologist Marcel Mauss, and the Cambridge political economist Geoffrey Ingham have long espoused similar arguments.

When barter has appeared, it wasn’t as part of a purely barter economy, and money didn’t emerge from it—rather, it emerged from money. After Rome fell, for instance, Europeans used barter as a substitute for the Roman currency people had gotten used to. “In most of the cases we know about, [barter] takes place between people who are familiar with the use of money, but for one reason or another, don’t have a lot of it around,” explains David Graeber, an anthropology professor at the London School of Economics.

So if barter never existed, what did? Anthropologists describe a wide variety of methods of exchange—none of which are of the “two-cows-for-10-bushels-of-wheat” variety.

Communities of Iroquois Native Americans, for instance, stockpiled their goods in longhouses. Female councils then allocated the goods, explains Graeber. Other indigenous communities relied on “gift economies,” which went something like this: If you were a baker who needed meat, you didn’t offer your bagels for the butcher’s steaks. Instead, you got your wife to hint to the butcher’s wife that you two were low on iron, and she’d say something like “Oh really? Have a hamburger, we’ve got plenty!” Down the line, the butcher might want a birthday cake, or help moving to a new apartment, and you’d help him out.

On paper, this sounds a bit like delayed barter, but it bears some significant differences. For one thing, it’s much more efficient than Smith’s idea of a barter system, since it doesn’t depend on each person simultaneously having what the other wants. It’s also not tit for tat: No one ever assigns a specific value to the meat or cake or house-building labor, meaning debts can’t be transferred.

And, in a gift economy, exchange isn’t impersonal. If you’re trading with someone you care about, you’ll “inevitably also care about her enough to take her individual needs, desires, and situation into account,” argues Graeber. “Even if you do swap one thing for another, you are likely to frame the matter as a gift.”

Trade did occur in non-monetary societies, but not among fellow villagers. Instead, it was used almost exclusively with strangers, or even enemies, where it was often accompanied by complex rituals involving trade, dance, feasting, mock fighting, or sex—and sometimes all of them intertwined. Take the indigenous Gunwinggu people of Australia, as observed by the anthropologist Ronald Berndt in the 1940s:

Men from the visiting group sit quietly while women of the opposite moiety come over and give them cloth, hit them, and invite them to copulate. They take any liberty they choose with the men, amid amusement and applause, while the singing and dancing continue. Women try to undo the men’s loin coverings or touch their penises, and to drag them from the “ring place” for coitus. The men go with their … partners, with a show of reluctance to copulate in the bushes away from the fires which light up the dancers. They may give the women tobacco or beads. When the women return, they give part of this tobacco to their own husbands.

So it’s a little more complicated than just trading a piece of cloth for a handful of tobacco.

No academics I talked to were aware of any evidence that barter was actually the precursor to money, despite the story’s prevalence in economics textbooks and the public’s consciousness. Some argue that no one ever believed barter was real to begin with—the idea was a crude model used to simplify the context of modern economic systems, not a real theory about past ones.

“I don’t think anybody believes that was ever a historical situation, even the economists writing the textbook,” Michael Beggs, a lecturer in political economy at the University of Sydney, told me. “It’s more of a thought experiment.”

Still, Adam Smith really did seem to believe barter was real. He writes, “When the division of labour first began to take place, this power of exchanging must frequently have been very much clogged and embarrassed in its operations,” and then goes on to describe the inefficiencies of barter. And Beggs says that many textbooks sloppily seem to endorse this viewpoint. “They sort of use that fairy tale,” he explains.

Part of the difficulty in imagining a pre-money world lies in the fact that currency has been around for so long. The first Indian money appeared during the sixth century B.C. and consisted of silver bars. The world’s first coins appeared in Lydia (modern day Syria) around the same time.

But even though money has been around for a long time, humans have been around for hundreds of thousands of years longer, and it may be a mistake to imagine that modern economics reflects some sort of primordial human nature.

“Economic theory has always got to be historically bounded,” Beggs says. “I think it’s a mistake to think you’ll find the workings of modern money by going back to the origins of money.” He does point out that, while barter may not have been widespread, it’s possible that it happened somewhere and led to money, just given how much is unknown about such a large period of time.

Even though some anthropologists have long known the barter system was just a thought experiment, the idea is incredibly widespread. And this isn’t just an academic curiosity—the idea of barter may have altered history.

“The vision of the world that forms the basis of the economics textbooks … has by now become so much a part of our common sense that we find it hard to imagine any other possible arrangement,” writes Graeber in Debt: The First 5,000 Years.

Graeber asserts that the barter myth implies humans have always had a sort of quid pro quo, exchange-based mentality, since barter is just a less efficient version of money. But if you consider that other, completely different systems existed, then money starts to look like less of a natural outgrowth of human nature, and more of a choice.

For one thing, the barter myth “makes it possible to imagine a world that is nothing more than a series of cold-blooded calculations,” writes Graeber in Debt. This view is quite common now, even when behavioral economists have made a convincing case that humans are much more complicated—and less rational—than classical economic models would suggest.

But the harm may go deeper than a mistaken view of human psychology. According to Graeber, once one assigns specific values to objects, as one does in a money-based economy, it becomes all too easy to assign value to people, perhaps not creating but at least enabling institutions such as slavery (in which people can be bought) and imperialism (which is made possible by a system that can feed and pay soldiers fighting far from their homes).

Whether or not one agrees with such broad claims, it’s worth noting that monetary debt, a byproduct of currency, has regularly been used to by some groups to manipulate others. Thomas Jefferson, for instance, suggested that the government encourage Native Americans to purchase goods on credit so they’d fall into debt and be forced to sell their lands. Today, black neighborhoods are disproportionately plagued by debt-collection lawsuits. Even after taking income into account, debt collection suits are twice as common in black neighborhoods as in white ones. $34 million was seized from residents of St. Louis’ mostly black neighborhoods in suits filed between 2008 and 2012, much of which was seized from debtors’ paychecks. In Jennings, a St. Louis suburb, there was one suit for every four residents during those years.

So if money is a choice, are there alternatives worth considering? Is a gift economy—which wouldn’t put people into debt, which relies on communal responsibility and trust—preferable to a system based on money? Or would people just take advantage of their neighbors?

It’s hard to answer that without actually seeing a modern gift economy in action. Luckily, modern gift economies actually do exist. On a small scale, they exist among friends, who might lend each other a vacuum or a cup of flour. There’s even an example of a gift economy on a much larger scale, albeit one that’s not always in operation: The Rainbow Gathering, an annual festival in which about 10,000 people gather for a month in the woods (it rotates among various national forests around the country each year) and agree not to bring any money. Groups of attendees set up “kitchens,” in which they prepare and serve food for thousands of people every day, all for free. Classical economists might guess that people would take advantage of such a system, but, sure enough, everyone is fed, and the people who don’t cook play music, set up trails, teach classes, gather firewood, and perform in plays, among other things.

Then again, it’s one thing to keep a community alive and well when everyone’s camping in a forest and they’ve all opted in to that vision. It’s quite another to imagine a gift economy enabling humans to build skyscrapers, invent iPhones, put air conditioners in every house, and explore space. (The same goes for collecting taxes and running large businesses.) Not that it’s an all-or-nothing situation: We already have gift economies among friends and family. Perhaps expanding that within small communities is possible; it’s certainly desirable.