Many environmental groups consider the Obama administration’s plan to regulate carbon-spewing coal plants, which aims to cut carbon pollution by 30%, as one of our last chances to win the fight against climate change.

But the vast majority of their top corporate partners – companies like Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, FedEx, UPS, Target and Walmart, which have worked with environmental NGOs for years – aren’t backing them up, according to a Guardian survey.

The survey consisted of calls and emails to nearly 50 corporations that work with three environmental groups – Environmental Defense Fund, The Nature Conservancy and the World Wildlife Fund US – that have identified the Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Power Plan as a top priority. These are Fortune 500 global companies that tout their sustainability efforts and celebrate their environmental partnerships.

Just three of them – Starbucks, Mars and Google – support the Clean Power Plan, which is a cornerstone of the Obama administration’s climate change efforts. Caterpillar and CSX Corp, a coal-carrying railroad, oppose the EPA plan. The vast majority take no position.

The reluctance of companies to take a stand raises questions about the depth of partnerships between companies and NGOs. By remaining quiet, these companies make it harder for the EPA to roll out the plan in the face of vehement opposition from fossil fuel companies and Republicans. “Silence isn’t neutral,” says Anne Kelly of Ceres, who is organizing companies to support the EPA.

The lack of public support could jeopardize the clean power plan, and – if the US isn’t able to make a strong climate commitment as a result – could ultimately undermine the success of the global climate talks in Paris this year.

The companies that won’t get involved say it’s because the regulation of power plant emissions is not core to their business. Environmentalists maintain that climate change is everybody’s business.

The Environmental Defense Fund, for example, says the EPA Clean Power Plan is “the most significant step in US history toward reducing the pollution that causes climate change”. More than 480,000 EDF members have signed petitions backing the EPA. Fred Krupp, EDF’s president, said: “Hiding from challenges is not what Americans do.”

Yet EDF’s corporate partners would appear to be doing just that. AT&T, DuPont, KKR, McDonald’s, Ocean Spray and Walmart are all sitting out the debate over what some activists describe as a make-or-break climate change initiative.

It’s the same story with the corporate allies of The Nature Conservancy and World Wildlife Fund. Lou Leonard, vice president for climate policy at WWF, says: “We think that companies should, absolutely, be engaging on climate policy.”

Thus far, though, WWF has failed to bring along its partners, including such corporate giants as Bank of America, Coca-Cola and Procter & Gamble. In an email, Coca-Cola says: “Our sustainability priorities are women, water and well-being – all areas that tie closely to our business.” Bank of America, which helps finance the coal industry, says by email: “We don’t have any information to share right now on the EPA Power Plan.” P&G did not respond to emails requesting comment. You can read all the corporate responses to the Guardian inquiries here.

Their silence means the loudest business voices on climate policy issues in Washington or the state capitals come from conservative trade groups, such as the US Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Manufacturers and the American Farm Bureau Federation, which strongly oppose the EPA’s rules.

The stakes are high. Electric power plants are the single largest source of carbon pollution in the US, accounting for roughly one-third of US domestic greenhouse gas emissions. In 2007, the US Supreme Court ruled that the EPA was required to regulate greenhouse gases as pollutants, and in 2013, Obama announced the agency’s intention to reduce power plant emissions. Since then, the EPA has proposed regulations for new and existing plants, while delegating many of the particulars to states to permit flexible rule-making.

For the most part, supporters and opponents agree that the rules would make it all but impossible to build new coal plants, requiring some existing coal plants to shut down and raising the cost of electricity.

That’s where the agreement ends. The EPA says the climate and health benefits from its plan far outweigh the estimated annual costs, a position embraced by green groups. Aside from EDF, WWF and The Nature Conservancy, activist groups like the Sierra Club and Greenpeace also support the plan. US climate action, they say, is especially important as the world moves closer to global climate talks later this year in Paris. “It is an enormously high priority for The Nature Conservancy,” says Mark Tercek, the group’s president and CEO.

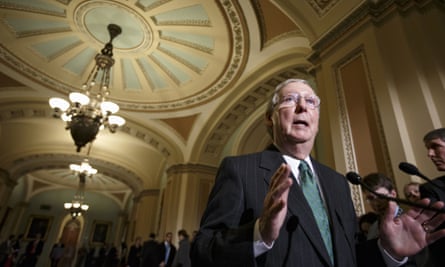

The EPA’s opponents, who have organized as the Partnership for a Better Energy Future, say that the power plant rules will raise energy costs to unacceptable levels, put US manufacturing at risk, threaten the reliability of the electricity grid and accomplish little in the way of greenhouse gas reductions. The issue has become a partisan battleground. This month, US Senator Mitch McConnell, a Kentucky Republican and the Senate majority leader, urged governors to refuse to enact the power plant rules.

The partisan nature of the debate is one reason why green groups have proven unable to enlist the support of their corporate allies. Businesses would rather not alienate powerful Republicans like McConnell.

As Glenn Prickett, chief external affairs officer for the Nature Conservancy, says: “Big companies that might be willing to join a bipartisan legislative effort are not going line up behind an initiative of the Obama administration strongly opposed by Republicans.” The Nature Conservancy and EDF are working together on a longer-term plan to build a bipartisan coalition for climate action in Congress, which is unlikely until after the 2016 presidential election.

The other reason why companies have stayed out of the fight is that they tend to save their lobbying power for matters that directly concern their interests. FedEx, for example, as an operator of trucks, supported the first-ever fuel efficiency and greenhouse gas standards for US commercial vehicles, which were enacted in 2007. FedEx is also one of the 20 biggest commercial users of solar energy, according to the Solar Electric Industries Association. But Mitch Jackson, who leads FedEx’s sustainability efforts, explained by email that the company isn’t taking a position on the power plant rules because they are “not directed at our industry sector”.

Likewise, the head of government relations for one of the world’s biggest companies told the Guardian: “There’s a reluctance if a regulation doesn’t get into your core competency to get into somebody else’s backyard. It’s an unspoken acknowledgment that you stick to your knitting.”

Bank of America, Citi and JPMorgan Chase all have high-profile sustainability programs and NGO partners, but they won’t engage in the coal-plant fight. “We have not taken a policy position on climate, or any other issue not directly related to finance,” says Matthew Arnold, head of environmental affairs at JPMorgan Chase.

By contrast, Google, Mars and Starbucks publicly support the EPA plan. In comments filed with the EPA, Google asked that the plan be strengthened. “EPA’s assessment of the potential for cost-effective, renewable energy opportunities is, if anything, conservative,” the company said. Mars and Starbucks signed a letter to Obama put together by Ceres’ Business for Innovative Climate and Energy Policy project. Other companies with $1bn or more in revenues that signed the letter include EMC Corp, IKEA, KB Home, Kellogg, Levi Strauss, Nestle, Novelis, SunPower, Symantec, Unilever and VF Corp.

Some companies have staked out a middle ground. Dow Chemical and GE filed comments on the EPA rules recommending improvements. Boeing and 3M have joined companies in the power sector in a small group called the National Climate Coalition, which support EPA’s goal of significantly reducing power-plant emissions, but are trying to influence the rules to insure that electricity remains reliable and affordable, according to Robert Wyman, an environmental lawyer with Latham & Watkins, who coordinates the coalition.

“We’re here to get to yes,” he says. “We’re not here to fight about the science.”

The fact that so few companies are willing to push for coal-plant regulation frustrates some environmentalists. The Environmental Defense Fund organized a webinar to explain the importance of the EPA plan to its corporate partners, says Tom Murray, who leads the nonprofit’s corporate partnerships.

“The next step up the corporate sustainability leadership curve needs to be aligning what you’re doing on corporate sustainability and strategy with policy advocacy,” he says.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion