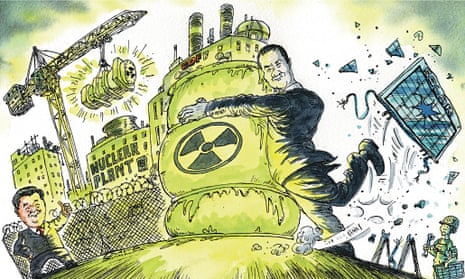

A glaring anomaly of British energy policy will be on display this week: the government will loudly trumpet a nuclear deal with China, and then will come a no-fanfare end to a controversial solar subsidy consultation.

President Xi Jinping will probably sign a heads of agreement with David Cameron that will allow the government to say that a new plant at Hinkley Point in Somerset is on its way.

The groundwork for the deal was done by George Osborne on his recent trip to Beijing, with the chancellor determined to roll away any obstacles that could halt China becoming a major investor at Hinkley – and beyond.

The chief developer of the new nuclear reactors in the south-west – the first for 20 years – is EDF, which has also been trying to woo state-owned Chinese companies to invest in the £24.5bn scheme.

Only by promising to allow the Chinese to build their own replacement plant at Bradwell in Essex have Osborne and Cameron finally won Beijing’s support for Hinkley. After that it will be up to EDF to press the final investment button and for construction to start in earnest.

Britain undoubtedly needs new electricity generating capacity as old nuclear and coal-fired power stations reach the end of their lives or are retired – in the case of the latter because of their carbon emissions.

And the public has been willing to give atomic power another chance on the grounds that greenhouse gases are a bigger threat than radioactive waste, safety issues and other risks uniquely posed by nuclear technology.

But EDF and its engineering partner Areva have queered their own pitch by presiding over mounting cost overruns and project delays at pioneering projects in Finland and France under the control of one or both.

Meanwhile the government has been forced to guarantee a subsidy price of £92.50 per megawatt hour for 35 years to EDF to get this far on a scheme that was meant to produce power in 2017 but now will not be ready till 2024 – and only then if it does not run into the kind of logistical and other difficulties that have hampered similar kinds of plants at Olkiluoto and Flamanville.

Ministers have been relentlessly supportive of nuclear, talking up the number of jobs being created – 25,000 in the construction phase – and talking down the worries about safety, waste, delays and national security.

At the same time the Conservative government has been waging what looks like a determined war against solar and other renewables, highlighted by a proposed 87% cut in subsidies from 1 January on rooftop solar panel installations.

More than 1,000 jobs have been lost in the past 10 days as three major solar installers have closed their doors in anticipation that ministers will bring burgeoning demand for small solar schemes to an abrupt halt.

Unlike the warm words of encouragement and firm policy help for nuclear, there has been a relentlessly negative attack on the solar industry, which ministers have suddenly decided should now stand on its own feet. There have been constant references to hard-pressed bill payers, with the intermittent nature of solar and wind being highlighted by the Department of Energy and Climate Change against the advantages of constant power from nuclear.

These generalisations hide a different truth. Renewable energy is largely a new UK private-sector success story, where costs are falling fast and which deserves considered and time-limited support. Nuclear power is a mature technology run by state-owned companies from France and China where costs seem to constantly rise and where 35-year price commitments at double the cost of existing wholesale power should not be being given.

With power capacity margins falling so low that many warn the lights could go out this winter, you have to conclude that the government lacks competence as well as vision.

Labour’s bank review must be radical

Like the Japanese soldiers who spent decades deep in the jungle believing the second world war was still raging outside, central bankers have a tendency to fight their old enemies, regardless of how much the world has changed.

With trouble brewing in global financial markets and little or no ammunition left in central bankers’ armouries, questions are growing about whether inflation-targeting – the regime that evolved after the searing experience of the 1970s inflationary shocks – is up to the job. Some experts fear that by focusing on stabilising prices, central bankers have put too little emphasis on growth, financial stability and unemployment. As a result, warned HSBC’s Stephen King recently, the world economy may be sailing towards an iceberg.

So the decision of Labour’s new shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, to commission the up-and-at-’em Anglo-American economist Danny Blanchflower to review the role of the Bank of England is timely. Blanchflower has been one of the fiercest critics of the Bank’s record, since leaving its interest-rate-setting monetary policy committee in 2009.

His new committee has serious heft. Blanchflower will be joined by monetary policy expert (and fierce critic of austerity) Simon Wren-Lewis; his fellow former MPC member Adam Posen; and former Treasury select committee chair John McFall.

British lefties have long had a deep-held suspicion of central bankers, believing they are small-c conservatives, fixated with assuaging the international bond markets – and McDonnell has previously expressed his scepticism about Bank independence.

But Blanchflower and his colleagues are expected to focus their attention more on whether paying attention to other indicators, such as unemployment or economic output, might help the monetary policy committee to steer around future icebergs.

Blanchflower is keen to examine whether a US Federal Reserve-style mandate, which includes promoting maximum employment as well as controlling inflation, might have helped the MPC to anticipate the turmoil of 2008-09 better — a labour market expert, he felt at the time that unemployment was a good indicator of the underlying health in the economy.

But he and his colleagues might also be wise to take a step back and ask whether an even more radical rethink of the best way to manage monetary policy is necessary.

Uber ruling is welcome

Black cabs are as quintessentially London as Nelson’s column or a red double decker, but few tears were shed for them by the travelling public after the legality of Uber’s operation was affirmed this week.

In truth, the ruling may not have been the watershed many hoped: Uber would have tweaked its app and rolled on. But the fact that the taxi trade is governed by rules so arcane that a judge had to decide if a smartphone is a meter highlights the problem.

Uber’s technology lets it slip through the regulatory net. When it comes to as safety, Uber in fact provides more reassurance, with details of drivers, journeys and transactions. The authorities should rightly beware its Silicon Valley “common sense”, which could ignore boring things like tax, access and congestion. But when consumers decry the regulation that is supposed to protect them, it clearly has to be overhauled.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion