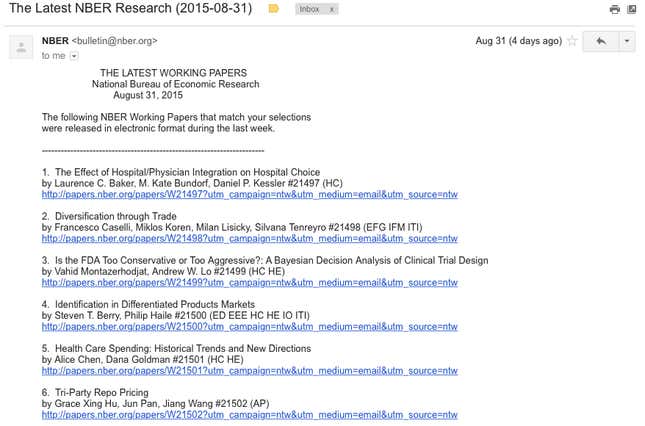

The weekly email that I and more than 20,000 others get from the National Bureau of Economics each Monday at 4:15am ET is something that I genuinely look forward to.

It’s a list of more than a dozen often fascinating new working papers from some of the best academic economists around on topics ranging from NFL player bankruptcy to a 600-year economic history of a French mill collective. But a deep injustice was revealed earlier this year—by one of the very papers in the weekly email.

The papers are presented in the email in order of when they were received and processed. It is basically random and impossible to game—but it turns out order matters a great deal.

Papers presented first on the email are much more likely to be viewed, downloaded, and written about in the wider world because of timing, not because of any particular merit. The first paper up, for example, is a full 30% more likely to get seen, downloaded, and cited by other researchers. The further you go down the list, the lower the number of views and downloads—until the last paper, which sees a spike.

And this is from a group of people that are disproportionately likely to be experts in the field, with very specific interests. Rather than shrugging it off, the group is now going to make sure that each paper is seen in each position by approximately the same number of people.

Under the old regime, many excellent papers got less attention for no real reason. The researchers attribute it to what’s called primacy bias—even the generally highly-educated and engaged audience for this newsletter fall victim to the tendency to pay more attention to what comes first.

Because of the way it’s structured—just paper titles are listed at the top—you have to click through to the NBER site to see an abstract and download the paper. That added to the tendency to just look at one or two earlier papers as opposed to scrolling through the entire list. (NPR has a great interview with one of the paper’s authors, available here, that gives more detail)

A group of economists is not one to take such data lightly. From an email sent by NBER president Jim Poterba yesterday (Sept. 3) to the list’s subscribers that explicitly cites the earlier paper:

To avoid inequities across working papers that result from list placement differences, beginning next week, the order of papers in each of the more than 23,000 “New This Week” messages that we send will be determined randomly. This will mean that roughly the same number of message recipients will see a given paper in the first position, in the second position, and so on.

The biggest winners, beyond people who are a bit late in submitting their papers, might be the authors of the study that prompted this shift. They get a rare instance of what economists call a “natural experiment” that should produce some fascinating new data on how list order affects behavior.