Brazil’s drive to nip illicit tree-felling in the bud has shifted the nature of the problem, according to researchers.

Small-scale illegal logging is – proportionally speaking – on the rise, says a report by the Climate Policy Initiative and the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro.

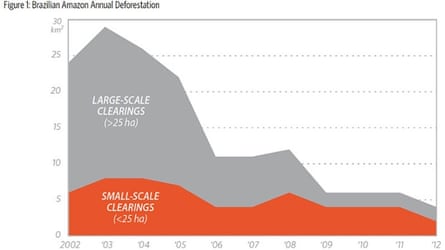

Deforestation rates fell nearly 80% from 27,000 sq km in 2004 to 5,000 km2 in 2012, following a strict regime of regulation, monitoring and enforcement.

But over the same period, destruction of patches smaller than 25 hectares has increased from a quarter of the total to more than half.

By clearing areas of that size – equivalent to 15-20 football pitches – illegal loggers can normally avoid detection from satellite monitoring.

“It is clear that Brazil’s efforts to curb deforestation are working,” said Juliano Assunção, the study’s author and a professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro.

“Our study shows, though, that there are still challenges. We need to step up forest protection strategies on smaller tracts of land.”

Smallholders’ practice of slash-and-burn agriculture is environmentally destructive, hacking away carbon-sucking forests to leave a scar in the landscape.

Researchers tracked tree-cutting in the large states of Mato Grosso and Pará to examine changes on government policies deployed from 2004 to 2012.

Conservation policies were more effective in soy-growing Mato Grosso, where any illicit felling by large and medium-scale landholders was easier to detect. Business boycotts on beef and soy linked to deforestation also played a part.

In Pará, predominantly small-size property holders eluded authorities, emerging as the leading agents of forest clearing in that state.

“This observation is so important,” notes Assunção, “because it teaches us that we can no longer think about deforestation as a single, homogenous problem across the Amazon.”

Brazil cut its greenhouse gas emissions 41% between 2005 and 2012, largely by slowing destruction of the vast Amazon rainforest.

And the country “has all the elements in place to reach zero deforestation in 2025,” said Paulo Moutinho, head of Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM), in June.

The same month, President Dilma Rousseff promised 120,000 km2 in reforestation, during a visit to the US. She stopped short of naming a date to end forest destruction.

Critics said the pledge would not go far against the 750,000 km2 of forest lost since 1970.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion