/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/46279792/GettyImages-77752684.0.jpg)

Given that Congress has become so utterly dysfunctional in recent years, it's tempting to think the upcoming presidential election will be fairly low-stakes. Does it even matter what Jeb Bush thinks about tax policy or what Hillary Clinton is proposing on paid leave? Hardly anything will pass.

But on global warming, it's a rather different story. Whoever gets elected to the White House in 2016 will have an enormous amount of influence over America’s climate policies — and they won't need Congress to act.

For that, you can thank (or blame) President Obama. Over the past six years, the Environmental Protection Agency has acquired unprecedented authority to regulate the nation’s carbon dioxide emissions. Obama has used that power to enact a slew of new pollution rules, including CO2 regulations on coal plants, all with the aim of cutting US greenhouse gas emissions at least 26 percent between 2005 and 2025.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3666726/white_house_emissions_goals.0.png)

(US INDC)

The EPA will likely keep this authority to regulate carbon dioxide for the foreseeable future — unless it gets altered by courts or repealed by Congress. And many of the biggest decisions on how to use it will be left to the next president.

If, say, Hillary Clinton wanted to expand Obama’s carbon rules to oil refineries or cement plants, she could. Conversely, if a Republican president skeptical of climate change wanted to bog down implementation of Obama’s CO2 rules for coal plants, he'd be able to do that, too. (Though, as we'll see, Republicans may not have unlimited power to scuttle Obama's climate policies.)

"Any future administration will have a lot of room to be either more ambitious or less ambitious," explains Michael Wara, an expert on energy and environmental law at Stanford. And how the next president uses the EPA could have ripple effects around the world — and even decide the fate of ongoing international climate talks with China, India, and other countries.

So far, the 2016 candidates have been vague about which way they'd steer the EPA. Clinton has said Obama's climate rules should be "protected at all cost," but she's given little sign of whether she might expand them further. Meanwhile, Republicans like Marco Rubio and Jeb Bush sound skeptical about tackling global warming, but they haven't said whether they might try to relax or even dismantle Obama's climate policies. So here's a look at what they could do.

Obama's climate policies give vast power to the president

US President Barack Obama wipes sweat off his face as he unveils his plan on climate change June 25, 2013, at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. Alex Wong/Getty Images

First, a recap of how the executive branch acquired so much power over US climate policy. Back in 2007, the Supreme Court ruled that the EPA must regulate greenhouse gases as pollutants under the existing Clean Air Act — if there's evidence that they endanger public health and welfare.

In 2009, Obama's EPA laid out this evidence, and that "endangerment finding" set in motion a series of rules to curtail US greenhouse gas emissions. Since this was being done under the auspices of the Clean Air Act, a law Congress had passed in 1970, no new legislation was required. The EPA could act on its own. The big actions so far:

- Stricter fuel-economy rules for vehicles: The first major rule came in 2011, when the EPA began regulating CO2 emissions from cars and light trucks. Under these rules, fuel-economy standards for new cars and light trucks will keep rising each year until they reach 54.5 miles per gallon in 2025.

- Stricter permitting for new power plants: Next, in 2012, the EPA announced strict CO2 rules for anyone who wants a permit to build a new coal or gas plant — rules that make it impossible to build new coal plants in the United States unless they can capture their own CO2 emissions and bury them underground (a technology still in its infancy).

- The Clean Power Plan: In 2014, the EPA proposed its most sweeping policy yet: new rules to limit carbon dioxide emissions from the nation's thousands of existing coal and gas power plants. Under this rule, to be finalized in 2015, the EPA will require all states to submit plans for reducing emissions through a mix of efficiency, switching from coal to gas, investing in renewables, or other options. Early estimates suggest these steps could reduce power-plant emissions to as much as 30 percent below 2005 levels by 2030.

- Methane, HFCs, and other steps: On top of that, the Obama administration has enacted a bunch of smaller rules, such as tightening energy efficiency standards for household appliances, regulating methane emissions from future oil and gas wells, and cracking down on HFCs, another potent greenhouse gas found in air conditioners.

Add it all up, and the White House claims these rules put the US on pace to reduce greenhouse gas emissions at least 26 percent between 2005 and 2025. But whether that actually happens will depend on the next president.

How the next president can strengthen — or weaken —Obama’s climate policies

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3670662/540027257.0.jpg)

Let's just make a few adjustments like so. (Erin Jonasson/AFR/Fairfax Images/Getty Images)

Okay, now let's assume it's 2017. There's a new president, and Congress is still totally gridlocked on climate change. What happens next?

The next president likely won't be able to dismantle Obama's climate policies entirely — not on his or her own. After all, the Supreme Court has effectively ordered the EPA to regulate greenhouse gases so long as there's evidence that they cause harm, and that evidence is quite solid. Only Congress could undo everything Obama's done, by revising the Clean Air Act.

Still, whoever occupies the White House and EPA will have a lot of say in how to implement Obama's climate rules. That sounds boring, but it's actually a key step. There's tons of leeway to strengthen or weaken these rules. Here are a few ways this could play out:

1) Fuel-economy standards could be tightened (or weakened) in 2017. Remember, the EPA's fuel-economy standards for new cars and light trucks are on pace to rise from their current 35 miles per gallon to 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025.

Yet those numbers aren't set in stone. These CAFE (corporate average fuel economy) rules are scheduled to come up for a midterm review in 2017. At that point, automakers may lobby to allow the standards to rise more slowly — particularly if sales of fuel-efficient vehicles have been sluggish due to low oil prices. Green groups, meanwhile, could push to make the standards stricter, or to have them keep increasing past 2025, to push vehicle emissions down even further.

So the next administration will have to decide. Leave the vehicle standards alone? Make them stricter? Weaker?

The one twist here is that due to a longstanding quirk of the Clean Air Act, California can threaten to create its own stricter standards if it's not happy with what the federal government is doing (and other states can join). Automakers really hate the idea of multiple sets of vehicle standards around the country, so they may prefer not to weaken the federal rules too much and risk having California go it alone.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3667202/181753792.0.jpg)

A plume of exhaust extends from the Mitchell Power Station, a coal-fired power plant built along the Monongahela River, 20 miles southwest of Pittsburgh, on September 24, 2013, in New Eagle, Pennsylvania. (Jeff Swensen/Getty Images)

2) The Clean Power Plan will live or die based on implementation. The EPA will finalize its rules for reducing carbon dioxide from existing power plants in the summer of 2015. It's a core component of Obama's climate policy — power plants are responsible for 31 percent of the nation's greenhouse gas emissions. But the next president will have enormous influence over how this plan actually works.

Assuming the rule holds up in court, it could prove difficult for the next president to simply hit the kill switch on the plan and start all over. But he or she will get to decide how to implement it — and that's arguably just as significant. After the rule is finalized, states will have another 14 months to submit plans for cutting emissions, though some will request extensions. That process could drag on until 2017 or 2018.

At that point, the EPA will review each state's plans for reducing emissions from its power plants and decide whether the plans are acceptable. An administration that really wants to tackle climate change can make sure states are doing as much as is feasible. By contrast, a president who was less concerned about global warming could allow states that wanted to, like Texas, to submit less-aggressive plans.

"There’s a lot of latitude in the review process," says Stanford's Michael Wara. "The history of the Clean Air Act shows this. If you have a president who doesn’t like climate policy, they could basically signal to the states that they’re going to give a lot of compliance flexibility and allow states to make assumptions in their plan that reduce their costs." This would likely involve seemingly arcane tweaks to models and baselines that would be harder for green groups to challenge in court.

Meanwhile, some states may outright refuse to submit any plans for reducing emissions. (Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-KY, is already urging states to do exactly this.) If that happens, the EPA has the authority to impose its own federal plan on the states. The agency will unveil the details of this federal plan in 2015, though, again, implementation would be left to the next president.

Meanwhile, industry groups are almost certain to challenge aspects of the rule in court. Adele Morris, the policy director for the Climate and Energy Economics Project at the Brookings Institution, points out that an administration hostile to Obama's EPA rule could defend it weakly in court. And if any parts of the rule get struck down, the next administration will get to decide how to redo it.

It all comes down to preference. "If you have an administration that's friendly to [Obama's] policy, then you'd have continuity in implementation," says David Doniger, director of the Natural Resources Defense Council's climate and clear air program. "But if you had an administration that wasn't as friendly, they could try to drag their feet or change the rules."

3) The next president will decide whether to regulate other sectors — like refineries. The Clean Air Act doesn't just cover vehicles and power plants. Technically the EPA has the authority to regulate carbon dioxide from other sources, as well. Oil refineries. Cement plants. Trucks. Airplanes. The agency is regulating methane leaks from new oil and gas wells, but it hasn't touched existing wells. And so on. These sources all add up.

The Obama administration is leaving most of the decisions about what to do with these sectors to the next president. If Hillary Clinton comes in and wants to expand the EPA's authority here, she can. If Marco Rubio comes in and doesn't, he may have to fend off lawsuits, but he can likely hold off on doing this for a long time.

Most candidates have been vague on these EPA rules

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3670844/464620780.0.jpg)

"Sorry, what's this about a federal implementation plan?" (Alex Wong/Getty Images)

At this point, we only have a hazy sense for what most US presidential candidates think about global warming. But given how much power they have at their disposal, they should give more detailed answers.

For instance, Hillary Clinton's campaign chair, John Podesta, claims that she'll put climate change and clean energy at the "top of the agenda." And Clinton has said the EPA's climate rules should be "protected at all cost."

Fine. So we know she'll veto any attempts by congressional Republicans to repeal the EPA rules altogether. But what else? Would she try to strengthen the fuel-economy rules during the 2017 midterm review? Would she want to expand the EPA's carbon regulations to oil refineries and chemical plants? Would she try to beat Obama's goal of cutting emissions at least 26 percent between 2005 and 2025?

On the other end of the spectrum, there's Marco Rubio, who says, "I do not believe that human activity is causing these dramatic changes to our climate the way these scientists are portraying it." But what does that mean in practice? Would he weaken the vehicle rules? Abandon the US goal of cutting emissions 26 percent?

Then there's Jeb Bush, who says he's "concerned" about climate change and that "we need to work with the rest of the world to negotiate a way to reduce carbon emissions." But, again, what does this mean? Would he keep Obama's climate rules in place? Strengthen them? Weaken them?

Some green groups have started to focus on these questions. "We definitely want to ensure that the next president is actually committed on building progress through the Clean Power Plan," Tiernan Sittenfield, senior vice president at the League of Conservation Voters, told me.

For now, many environmentalists have mainly been pressing Clinton on what she thinks of the Keystone XL pipeline. Yet that issue will probably be resolved before Obama leaves office. The EPA rules are far more relevant for the next administration.

The EPA rules can't "solve" global warming — but they could influence global climate talks

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3670588/1692711.0.jpg)

Still not even close to enough. (David McNew/Getty Images)

It's worth being precise about what the EPA can and can't do here. The executive branch has acquired sweeping authority over the nation's greenhouse gas emissions. The Obama administration estimates that this authority alone could push emissions down 26 to 28 percent between 2005 and 2025.

Looked at one way, that's a huge deal — a decisive break from the past, when emissions would go up and up seemingly without end. Looked at another way, it's a pittance.

To help avoid drastic global warming, the United States will probably need to push down emissions 80 percent or more by midcentury. That would require truly staggering changes. It wouldn't be enough for coal and gas plants to get slightly more efficient under EPA rules. We'd have to replace virtually our entire energy system with a new, cleaner one.

That's the sort of thing that only Congress can really do. Only Congress can fund R&D for new technologies or offer subsidies for clean energy. Only Congress can bring about dramatic changes to our grid infrastructure. Only Congress can enact an economy-wide carbon tax. Barring some creative flexibility on regulations, these are things the next president just can't accomplish without cooperation from the House and Senate.

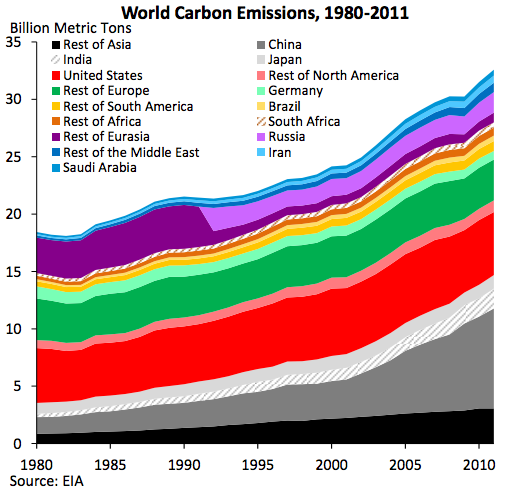

Where the EPA rules could have a more important effect is on the international stage — at least in the near term. Remember, the United States only accounts for about 17 percent of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions. There's also China, India, Brazil, Europe, Russia, and so on. That's why international cooperation on climate change is so crucial.

(White House Council of Economic Advisers)

Right now, the world is groping toward a very, very weak international agreement. The US put forward its pledge to cut emissions at least 26 percent between 2005 and 2025. That spurred China to respond by vowing to get its emissions to peak around 2030. Other countries have started to pitch in, too.

Add all these pledges up, and we're still not close to tackling global warming. The Climate Action Tracker estimates that we're on pace for global average temperatures to rise 3.1°C (or 5.6°F) above pre-industrial levels, give or take — a seriously disruptive change.

Even so, some experts think even these weak promises could lead, iteratively, to stronger action over time. "You can see how those plans could start to connect together and create a positive negotiating dynamic," David Victor, a political scientist at UC San Diego's School of International Relations and Pacific Studies, told me. "The encouraging precedent here is in trade ... You build credibility and trust over time and then move to bigger issues."

The next US president can help decide how this agreement continues to evolve in the years to come. The US can keep pushing its own emissions down and try to persuade countries like China and India to respond in kind. Or it could abandon this budding framework entirely.

Abandoning the US climate targets, says Wara, "would do real damage to whatever credibility the US has left on the international stage. What Obama has done with China is a big step in changing the dynamics in a very positive way. And if the US were to walk away from that, that would be very damaging for future climate negotiations and commitments."