Hedge Fund Industry Overstates Performance Claims: New Research

A growing body of evidence suggests hedge funds don't live up to the hype -- a finding especially important for institutional investors, including the pension funds that ensure the retirements of millions of teachers, firefighters and other public employees. Now, two studies reveal the chief marketing strategies employed by the hedge fund industry substantially overstate returns and benefits.

The first paper attempts, in part, to estimate hedge funds’ actual returns after correcting for certain biases that arise from the way hedge funds report their data. These biases, the authors write, “make hedge funds look misleadingly attractive.”

From 1996 to 2014, major hedge fund tracking indexes reported an annual return of 12.6 percent. But when the researchers adjusted for reporting biases, returns came in at half that total: 6.3 percent.

For a pension fund custodian trying to choose between the broader stock market and hedge-fund investments, the difference would be critical. During the same timespan, the S&P 500 index of major publicly traded companies saw annualized returns of 8.5 percent. Add in substantial management and performance fees and hedge funds don’t look so hot.

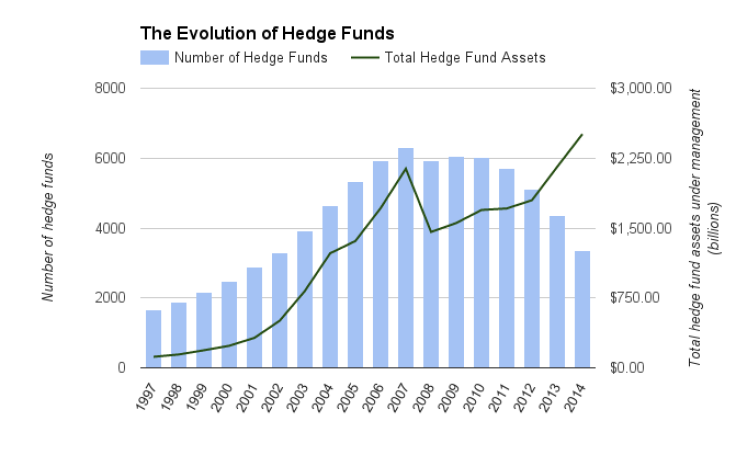

“It’s important for policy debates and for the public to have a better idea about the totals -- how many hedge funds are there and how are they performing?” said Mila Getmansky Sherman of the Isenberg School of Management, one of the paper’s coauthors.

Though defined-benefit pension funds reduced their hedge fund holdings after the financial crisis, they've increased their allocations since. About 8 percent of public pension assets are now held in hedge funds, totaling nearly $600 billion in retirement savings.

The biases the researchers examined stem from the way indexes of hedge-fund performance operate. Hedge funds aren’t obligated to report their returns to anyone but their clients. At the same time, federal law bars them from advertising in print or over airwaves. To get their names out, then, many hedge funds report their wins and losses to independent subscription-based firms.

“Much of what we know about hedge funds, and most of the empirical research on this industry, depends on such archival data,” the authors write, citing databases such as Hedge Fund Research, Lipper Tass and BarclayHedge.

But that reporting system introduces several biases. For one, hedge funds can voluntarily opt in or out of these indexes. When they’re on a hot streak, it makes sense to report. During a downturn, however, hedge funds might bow out of the databases, erasing evidence of subpar gains. And funds that had been included but later dissolve are wiped from the records.

“By excluding the hedge funds that have reported before but are not reporting now, you are usually biasing the returns upwards,” Sherman said.

Moreover, when funds enter the index after a long run of successes, they can choose to include any level of past returns in their reporting, an option that naturally favors positive numbers. There’s also evidence hedge funds might delay sending their data to the databases by up to several weeks to mask underperformance.

These biases, among others, have the overall effect of skewing the industry’s publicly reported results sharply positive. That means when custodians of public funds -- like Florida’s State Board of Administration -- take what seems like an objective view of the wider hedge-fund universe, they could be seeing a mirage. And when federal agencies like the Government Accountability Office cite hedge-fund indexes in reports, they might inadvertently present an inaccurate picture.

In particular, industry indexes have been regularly cited to show hedge-fund performance during the financial crisis of 2008 while negative, outperformed the tanking stock market. But given that, foundering hedge funds can exit the indexes.

This isn’t to say individual hedge funds are misreporting their returns to clients. “We’re not talking about mismanagement or doing something wrong,” Sherman said. In addition, many large and successful funds don’t report to indexes like Lipper Tass, the database the authors of the study examined. Including their returns, many of which are secret, could skew returns back up.

The authors of the study -- Sherman, Andrew Lo of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Lo’s colleague Peter Lee -- are also keen to point out two myths about hedge funds: “The first myth is that all hedge funds are alike,” they write. “The second myth is that all hedge funds are unique.”

It’s that latter contention that drove two Australian researchers to look into strategies hedge funds use, and how that affects results. These strategies purport to offer different risk and return profiles, suited to various types of investment needs. But most hedge funds, the study found, failed to exhibit evidence of uniqueness.

The classic long-short strategy, for example, offers moderate risk and returns, with positions in rising stocks “hedged” with shorts, bets that stocks will fall. More bespoke event-driven strategies, meanwhile, try to capitalize on market events like mergers to score big. These funds promise higher returns, along with higher risks. Each is “active” in its own way -- it relies on managers to seize opportunities actively, rather than passively riding the broader market.

One would expect these various strategies to result in sharply different patterns in returns. That’s not what the researchers found, however. “Most hedge-fund managers are passive, not active,” they write.

Only 20 percent of the hedge funds the authors examined from 1990 to 2010 exhibited patterns that were “nonlinear” -- meaning they diverged distinctly from the wider market. In contrast, two-thirds of the funds studied appeared passive, like a low-fee index fund that simply follows the S&P 500.

Since institutional investors justify many hedge fund investments in light of their ability to hedge wider economic conditions -- basically, to zig when the market zags -- it's important to know which hedge funds actually show this tendency. According to the researchers, Mikhail Tupitsyn and Paul Lajbcygier of the Australia's Monash Business School, surprisingly few funds do.

And although funds that used event-driven strategies were more likely to be distinct from broader market returns, they were less likely than more passive funds to show strong returns.

These studies aren’t the first to cast the hedge fund industry in a less-than-flattering light, and concerns over fees and middling performance have driven several public pension funds to pull their hedge fund investments. The largest of these, California’s CalPERS, yanked its $4 billion hedge fund position last year.

But public pension allocations to hedge funds continue to grow, according to Paamco, a California institutional investment firm that focuses on hedge funds. In 2014, large public pensions' hedge-fund holdings outperformed their benchmark, the HFRi, 9.1 percent to 6.4 percent.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.