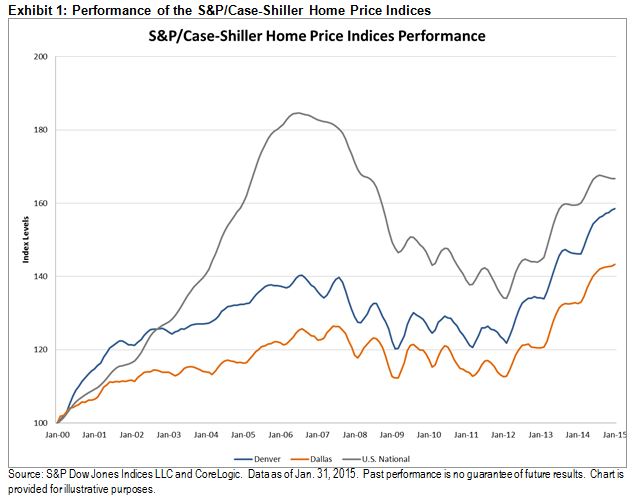

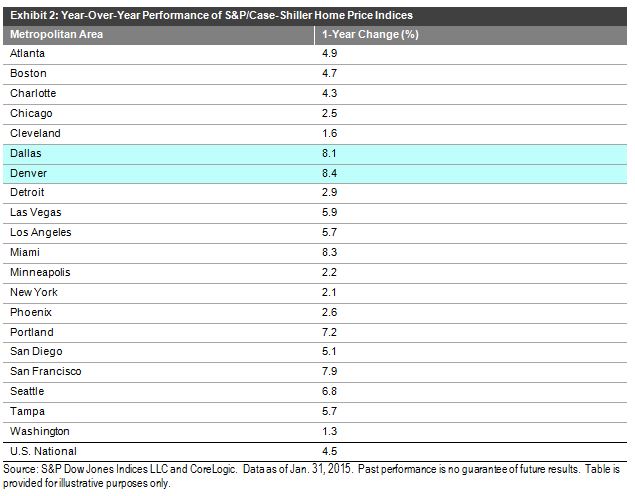

S&P Dow Jones Indices offers information for hundreds of indices on our website, but two in particular drive a large portion of our traffic: the S&P 500 and the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices.

It’s easy to understand why people would be searching for the S&P 500. By using this popular index and the financial products tied to it, you can measure your portfolio’s relative performance, invest in the equity market, hedge against risk, and even lever up your exposure.

And what can you do with the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices? Well, up to now, exactly this: see how much aggregate home prices have gone up or down.

You may wonder why the S&P 500 is presently so much more useful than the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices. This is due to the fact that investment companies can buy, hold, and sell the shares that make up the S&P 500. This allows investable products to exist.

But what can be done with an index made up of single, residential homes that are privately held and rarely bought and sold? So far, the answer has been “not much,” but this is changing.

Some clever product designers are exploring how the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Prices Indices can be used to shift home price risk from one party who wants less of it to another party that wants more. This article highlights one such solution, which allows homeowners to monetize today the future appreciation of their homes. Other interesting concepts will likely follow.

These products work by carefully matching investors willing to assume opposing sides of a trade. The first task is for these parties to agree on a price, which, in the case featured in the article, is to be determined by the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices at a point in the future. The people using the product must also agree to a holding period for the transaction.

It’s important that better tools emerge to help homeowners manage risk. A lot is at stake. Homes represent approximately half of the net worth of US households. Currently, this wealth is difficult to unlock without selling your home, and no one wants to go through that costly transaction unless they really have to.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.