When Booker O'Neal reviewed his investment statement last fall, he noticed something odd: All the stock market indexes were up for the year, but his nest egg was down 3 percent.

Even worse: O'Neal, a retired marketing executive in Kansas City, Mo., was losing another 1 percent to the annual fee his financial advisor of four years was charging him to manage his account. And that was on top of the fees for the funds in his portfolio. "I asked myself: What am I getting for that?" said O'Neal.

It's a question a lot of investors are beginning to ask—both about the fees they're paying for advice on their retirement accounts and the hidden costs of the investments within them.

Read More: Is the 401(k) experiment a failure?

Last month, President Barack Obama put the spotlight on both when he announced support for a Labor Department proposal that would require brokers and other financial advisors to abide by the same "fiduciary" standard—meaning they would be required to put clients' interests before their own.

The White House estimates clients lose up to $17 billion a year in fees.

Obama cited brokers who get compensated financially "for steering people into bad retirement investments that have high fees and low returns." Such recommendations, the president said, can add up to big profits for brokers over time in commissions and fees, and big losses for clients—up to $17 billion a year, according to White House estimates.

In a white paper released this week, the financial industry argued that brokers are already "thoroughly" regulated and that existing investor protections "prohibit broker-dealers and advisers from receiving excessive compensation and prohibit recommendations of investments at unfair or unreasonable prices."

But even if your advisor charges a flat fee and gets no compensation for recommended products, or takes a flat percentage of your total portfolio annually as O'Neal's did—or you invest on your own—you're still paying fees and expenses on the various financial products in your portfolio.

And those can be much harder to calculate—and much costlier—than an advisor's fee.

"The vast majority of individual investors... haven't the slightest clue as to how much they are forking over."

"The vast majority of individual investors, even high-net-worth investors, haven't the slightest clue as to how much they are forking over," said Tony Robbins, author of "Money: Master the Game." "I thought I knew the various fees, but ... I realized there were more layers to the onion."

Sheryl Garrett, a certified financial planner and founder of the nationwide Garrett Planning Network, explained: "There are so many different ways that custodians and financial service companies are receiving compensation. There are explicit fees, sure, but then the list goes on and on. Most people don't have any idea."

Read More: How funding shortfalls put pensions in peril

Most investors are familiar with the "expense ratios" associated with mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (or ETFs). That's the annual fee that funds charge shareholders—or the percentage of assets deducted each year for fund operating expenses—and funds are required to disclose that to investors. Those have come down in recent years, even for active funds, but the average mutual fund still charged an expense ratio of 1.25 percent in 2013, according to the most recent figures from fund-research firm Morningstar.

But as Garrett points out, other fees and expenses—from advertising expenses to redemption fees—can add another 50 or 75 basis points. "So the real expenses are closer to 2 percent, and that's without paying an advisor," said Garrett. "That's huge."

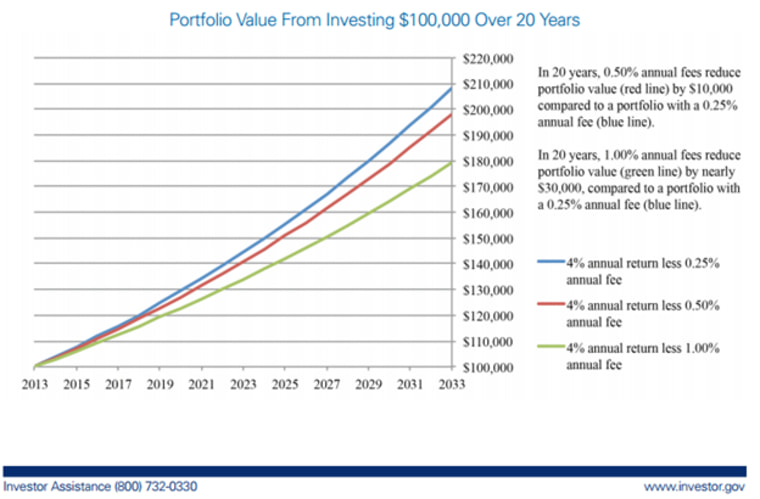

How huge? Over the course of two decades, even a 0.75 percentage point difference in annual fees can translate to a difference of $30,000 for a portfolio with a one-time $100,000 investment, according to Securities and Exchange Commission. (See chart below.)

"The brokerage industry has lulled us all to sleep and/or taught us that the fees are inconsequential," said Robbins. "Nothing could be further from the truth."

As awareness about fees has grown—due in part to vocal critics like Robbins and Vanguard Group founder Jack Bogle (who, admittedly, stands to benefit from it as his firm pioneered low-cost index funds)—so has the number of lower-cost financial products and services.

Since Bogle launched the first retail index fund in 1976, hundreds of different low-cost index funds have sprung up. The funds, which carry a lower expense ratio than active mutual funds because they trade less often and aren't actively managed, have soared in popularity in recent years. In December, Morningstar reported that over the previous year, active U.S. equity funds lost $91.9 billion in outflows while passive U.S. equity funds drew in $156.1 billion.

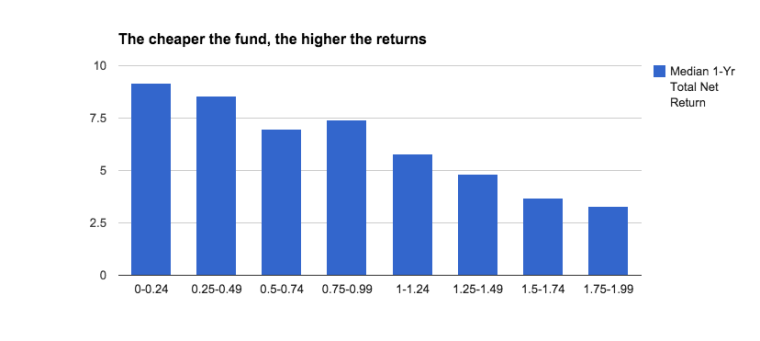

That's in large part because there hasn't been a clear correlation between higher fees and better performance, which makes it hard to justify paying more for a fund. Actively managed funds typically have the highest fees, but not always the best performance—something that's been pointed out by critics and researchers in recent years.

Read more: Four Americans share their struggles with retirement savings

To be fair, some active fund managers do consistently beat the market and earn the extra fees they charge investors. Other managers argue that their true value is in protecting clients from big losses when the market tanks, and not necessarily in delivering the biggest total returns.

But a 2014 report by the S&P Dow Jones Indices found that 60 percent of large-cap managers, 58 percent of mid-cap managers and 73 percent of small-cap managers had underperformed their benchmarks in the previous 12 months. And over the previous five years, more than 70 percent of domestic equity managers had failed to deliver returns higher than their respective benchmarks.

And in an analysis of a million portfolios over the previous 12 months, online investment manager SigFig found that, in general, lower-priced funds consistently performed better than those that cost more.

Over the last few years, at least a half-dozen free services like SigFig have emerged to help investors decipher what they're paying now in fees and look at lower cost alternatives. (Others include GuardVest, Personal Capital, and FeeX. Some, like Personal Capital and SigFig, also offer advisory services.)

When Christopher Norton, a 31-year-old Boston-based information technology consultant, used FeeX to analyze his IRA, he realized he was paying 0.8 percent in expenses on the target-date fund where he'd put much of his money. "I hadn't considered the expense ratio as part of the decision-making process until then. I didn't even realize that funds existed with lower fees," said Norton.

"I didn't even realize that funds existed with lower fees."

Within a week, he'd reallocated his money into a similar fund that had a 0.1 percent expense ratio. "That one simple change could save me $50,000 or $75,000 over the long run—and it took me a half an hour."

Advisors say fees are also starting to play a bigger role in clients' decision-making process.

"We're having a lot more discussions about them," said Jeffrey Sharp, a longtime investment advisor with SilverStone Asset Management in Omaha, Nebraska. "There's an awareness today that didn't exist even 36 months ago. The challenge is that, even with all this increased awareness, the typical investor still doesn't know what he's paying."

As that changes, the movement from active to passive funds and other lower-cost products is likely to accelerate. And that could give investors a much-needed boost in their efforts to set aside enough for retirement.

O'Neal, the recent retiree in Kansas City who left his advisor after analyzing the fees he was paying on his underperforming portfolio, linked his accounts to SigFig last fall and learned that he was paying expense ratios as high as 0.74 percent on his funds. After moving his money into lower-priced funds, he was able to lower his aggregate expense ratio to 0.11. And his portfolio is up for the year.

He doesn't dwell on the money he may have missed out on in past years. But as O'Neal looked over his accounts recently, he said, "I was satisfied."