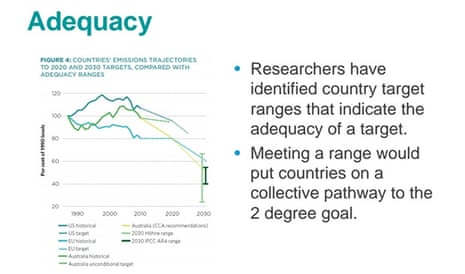

The chart above illustrates the huge question confronting Australian policy on climate change.

The top line on the chart – produced by the independent Climate Change Authority – shows United States’ greenhouse gas emissions as a percentage of what they were in 1990, with a dotted line to show the reductions the US has promised by 2025.

The bottom line shows the European Union’s emissions by the same measure, with a dotted line showing the reductions the EU has promised by 2030.

The vertical lines at the side show two different calculations of where emission reductions need to be by 2030 to give the world a chance of limiting climate change to 2C.

And the middle line shows Australia’s emissions, but the dotted line is where the authority thinks Australia’s emissions should be headed by 2030 – not what the Australian government has promised.

The Abbott government is in the process of deciding on its post-2020 emissions pledge – where it intends to draw that dotted line – and over the weekend released a well-flagged discussion paper about how it would make the decision by mid-year, ahead of the United Nations climate conference in Paris in December.

But many observers are deeply alarmed that the discussion paper does not mention the 2C goal, but does mention a scenario that could result in almost 4C global warming.

Discussing Australia’s special “national circumstances”, the discussion paper says that “for the foreseeable future, Australia will continue to be a major supplier of crucial energy and raw materials to the rest of the world, especially Asian countries. At present, around 80% of the world’s primary energy needs are met through carbon-based fuels. By 2040, it is estimated that 74% will still be met by carbon-based sources because of growing demand in emerging economies.”

A footnote confirms that estimate comes from the “new policies scenario” of the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook 2014 – which was a baseline calculation of what would happen if countries implemented only the policies announced at that time, a scenario seen as unacceptable because it would pave the way for at least 3.6C of global warming.

“This issues paper reveals a government risking failure of this key test of climate credibility,” said John Connor, chief executive of the Climate Institute.

“A world of 4C warming would be disastrous for Australia’s economy, security and environment. Current global policies do have us on the path but, unlike in Australia, other major emitters are moving to increase, not decrease, credible climate action.”

The Climate Change Authority has said Australia needs to reduce emissions to between 40% and 60% of 2000 levels by 2030 to be taking on its “fair share” of global emission reduction efforts.

The Climate Institute’s submission to the authority recommended reducing emissions below 2000 levels by 40% by 2025 and to achieve net zero emissions between 2040 and 2050.

The discussion paper asks for submissions by 24 April on what Australia’s target should be and what policies might be implemented to achieve it that were “complementary” to the government’s $2.55bn Direct Action plan.

Independent modelling has suggested Direct Action does not have enough money to meet even the 5% target, but the government insists it will easily achieve its aims. All analysis suggests it would be extremely difficult to “scale up” to a higher target.

Modelling has also found that cutting emissions further than 5% under Direct Action would be prohibitively expensive – the same charge levelled by the Coalition minister Malcolm Turnbull when he explained in 2011 that continuing to use a big government taxpayer-funded scheme to reduce emissions in the long term would “become a very expensive charge on the budget in the years ahead”.

The Climate Change Authority, which the Coalition has unsuccessfully sought to abolish, will report on its final recommended post-2020 emissions reduction targets next month.