Water’s Major Role in Disasters Not Matched in New Framework to Reduce Risk

Beyond Sendai, water community turns attention to Sustainable Development Goals.

By Codi Kozacek

Circle of Blue

International negotiators in Japan last week signed a new agreement to protect communities from natural disasters like floods, droughts, cyclones, and tsunamis. The agreement, negotiated in Sendai, a northern Japanese city near the Pacific, aims to reduce mortality and economic losses from disasters and guides actions by governments, aid organizations, and researchers to prevent and respond to disasters over the next 15 years.

The Sendai agreement was reached at the third United Nations World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction. The conference took place exactly four years after a massive 8.9-magnitude earthquake sent tsunami waves hurtling into northern Japan, killing more than 15,000 people. Sendai itself was inundated by a 10-meter-high wave. In 2012, the city’s work to rebuild was recognized as a role model for the U.N.’s Making Cities Resilient Campaign. The agreement signed there this month sets out four priorities:

-

1. Improving the understanding of disaster risk.

2. Improving planning and coordination between communities and relevant agencies.

3. Increasing investment in risk reduction and prevention measures.

4. Rebuilding after disasters in ways that reduce risk in the future.

The agreement incorporates water into recommended actions under three of these four priorities. It lists water in directives to promote transboundary cooperation over shared resources, to take disaster risk into account when planning rural development, to increase the resilience of infrastructure, and to support efforts to raise awareness of water-related risks (see sidebar). The measures mark progress from the preceding 2005 Hyogo Framework, which mentioned water in two out of its five priority actions, but stopped short of strongly incorporating water.

“Things have changed a little bit since water obviously receives a little more space,” Ursula Schaefer-Preuss, chair of the Stockholm-based Global Water Partnership, told Circle of Blue the day before the Sendai Framework was finalized. “This means, in the framework draft, water is only mentioned in connection to how to achieve the priorities at national and local levels, and at global and regional levels.”

“We have to see this as a first step, still hoping that water, if not in this context, gets the appropriate attention in the sustainable development goals negotiations which will be concluded in September,” she added.

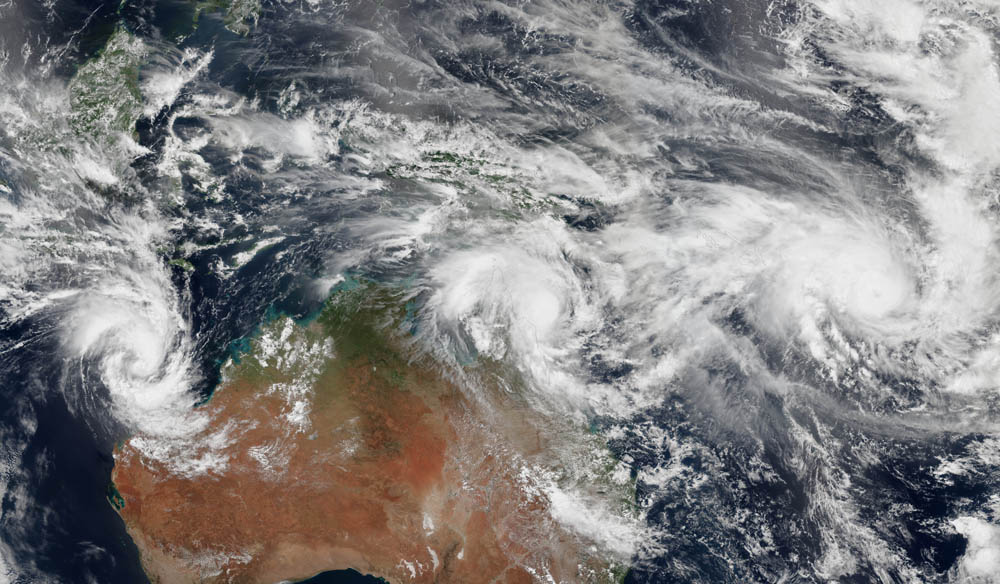

The Framework, however, does not reflect the outsize role that water plays in global disasters. Droughts and floods caused 70 percent of the $US 2.5 trillion in economic losses from disasters so far this century, according to the United Nations. A study released last week by the Food and Agriculture Organization found that, in the agricultural sector alone, droughts account for more than 85 percent of livestock damages and losses, while floods cause nearly 60 percent of crop damages and losses. Massive floods in the Himalaya two years ago and the severe droughts currently plaguing California and Brazil underline water’s central role in some of the world’s most costly disasters.

The Sendai conference was the first of three major international negotiations on the docket this year and will give direction to the world’s efforts to curb climate change and usher in a more sustainable development model. The United Nations summit to adopt new Sustainable Development Goals will take place in New York this September. The year culminates with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) conference in Paris, where representatives could finally reach a global deal to cap greenhouse gas emissions. Water’s integral role as a medium through which communities experience short-term disasters and long-term climate change challenges alike make it a critical tool for coordinating action in these three areas.

“The disaster risk reduction community and the climate adaptation community have basically been separate,” John Matthews, coordinator of the Alliance for Global Water Adaptation (AGWA), told Circle of Blue. “They have not –in terms of how they handle funds and how they envision projects, how they think about risk, how they are handled from a bureaucratic or administration perspective—they’ve been very separate worlds.”

“If we don’t have a [disaster risk reduction] community that is really thinking about both the climate role and how that might be happening in future disasters, it might cause us to really miss how it is we prepare for, assess in advance, and prevent many kinds of disasters,” Matthews continued. “I think that water really plays a central role in that–trying to transmit those two divisions, those two ways of seeing risk, into a single cohesive unit.”

Water, Climate, and Disaster Risk Action Kept Separate

Negotiators, however, have been slow to adopt commitments that piece together work in what have historically been different sectors. Water, for example, has largely been confined to goals to increase access to clean drinking water and sanitation, despite growing acknowledgement of its role in energy production, food security, and natural disasters. While water featured prominently in a landmark climate agreement signed between the United States and China last year, it did not make an appearance in the latest UNFCCC document signed in Lima last December.

“Well-coordinated water management integrated in climate and disaster risk reduction policies would be beneficial for efficient and comprehensive responses when inevitable disasters occur; it would strengthen economies as preventive measures are less costly than relying on emergency responses, and it would decrease the risk for those communities who are the most vulnerable and already carry a high burden e.g. with diminishing ecosystem services due to the impacts of climate change,” Sofia Widforss, program manager of international processes at the Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI), wrote in an email to Circle of Blue.

Even action on climate change has been avoided in the context of disaster risk reduction. Climate change is mentioned throughout the Sendai Framework, but only in relation to assessing and preparing for future risks.

“It was notably there in the room that countries hesitated to agree upon issues which could have discussions in Paris, or another way, should have discussions in Paris rather than here,” Cees van de Guchte, manager of climate adaptation and risk management at the Delft-based Deltares research institute, told Circle of Blue.

The Sustainable Development Goals could offer a vehicle to combine the sectors. One goal in the draft text focuses specifically on water, while another promotes action on climate change. A third, aimed at increasing the resilience of cities, incorporates the Sendai Framework to reduce disaster risk. Water and climate change issues may be taking a step back, however, as preliminary negotiations on the SDGs take place in New York this week.

“There is also a feeling like, in many of those discussions, there is an attempt at staying away from climate change and an attempt to step away from thinking about water in a more systematic way,” Matthews said. “That is an area of real concern. What we want, what I want, and what I think many in the water community want, is that we have a sense of momentum that’s moving toward the Paris COP.”

Urgency of Disasters Lacking for Climate Change

Disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation are closely interrelated in the context of water issues, according to Van de Guchte. Water infrastructure like dams and seawalls and integrated water management in cities, for example, could help communities build resilience to disasters and withstand future climate changes. Similarly, acting on climate change could reduce the risk of more intense disasters.

“SIWI believes that there is a need to focus on preventive measures of the underlying drivers of disasters, rather than taking a reactive approach to reduce or compensate for disaster losses,” Widforss wrote. “This is because hydro-climate hazards such as droughts and floods bear extremely high costs on society, exacerbating inequalities while being disproportionally borne by those who are already poor and vulnerable.”

Climate change action and disaster response, however, happen on very different time scales.

“From Vanuatu recently or the Philippines, the feeling for urgency is more there with disasters,” Van de Guchte said. “It is on this item that they differ—disaster risk reduction and adaptation to climate change—they differ.”

In places like the Netherlands, success in reducing exposure to the immediate risks of disasters can also hinder local action on climate change, he added.

“On the local level there’s not so much a feeling of urgency to act,” Van de Guchte said. “People think, oh, we are safe here. The dikes are there, the national government and also local governments are taking care of our safety against flooding, we have enough drinking water around, we don’t have food problems, so we don’t notice so much of climate change.”

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!