Although the low volatility anomaly was first documented more than 40 years ago, it was the trepidation and volatility in the years following the most recent financial crisis that propelled the concept to the forefront of investor interest. In recent years, the phenomenon has been well covered, by both academics and the investment community, in the form of innovative financial instruments that exploit the anomaly and subsequent attraction of assets to those vehicles. The low volatility anomaly exists not just in the U.S., but instead seems to be universal. The current debate is less focused on the existence of a low volatility effect and more on the construction of various strategies to exploit the phenomenon.

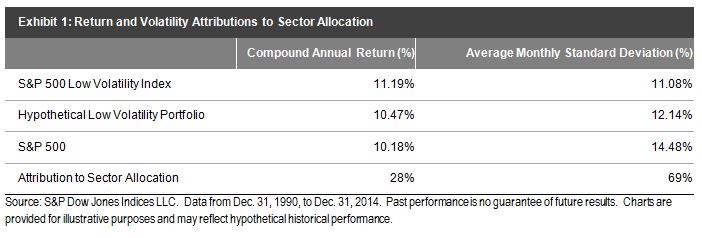

In the U.S., for example, the S&P 500® Low Volatility Index outperformed its benchmark, the S&P 500, from 1991 to 2014 by 101 bps compounded annually—with 31% less volatility. What is the reason for its success? Our rankings-based method of portfolio construction not only screens for stocks by factor, it also weights by factor (or the inverse of the factor, in this case) to achieve its objective. This methodology has resulted in large sector weights, historically.

However, strategic sector tilts don’t paint the complete picture here. If we only apply the returns of the S&P 500 sectors to the respective sector weights in S&P 500 Low Volatility Index over the last 24 years, the “hypothetical” low volatility portfolio can account for 69% of the total risk reduction. This means that being in the “correct” sector during this period accounted for more than two-thirds of the volatility reduction achieved by the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index (see Exhibit 1). In the same period, the return increment attributed to being in the “correct” sector was only 29%, from which we can conclude that more than two-thirds of the outperformance is idiosyncratic to S&P 500 Low Volatility Index’s methodology.

As is the case with many factor-driven portfolios, various portfolio construction methods can result in lower volatility. The ability to protect the portfolio in relatively stable sectors is a feature—not a side effect—of the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index’s rankings-based methodology.