Life may begin at 40, according to any number of Hallmark cards, but by 45, your chances of ever landing a major raise are pretty much dead. At least, that’s one of the many takeaways from a recent paper by a group of Federal Reserve researchers in Minneapolis and New York, who used a massive trove of Social Security Administration data dating back to 1978 to analyze how men’s earnings evolve over time.

For the rich and poor alike, the economists found that “the bulk of earnings growth” happens in the first 10 years of work, typically between the ages of 25 and 35. During the next decade of their career, men can expect smaller raises overall. After 45, those in the bottom 90 percent of lifetime earners see their earnings decline as a group, in part because people often start cutting back their hours around that time, especially if they do manual labor for a living. Meanwhile, even 1 percenters only see relatively minor pay bumps after middle age.

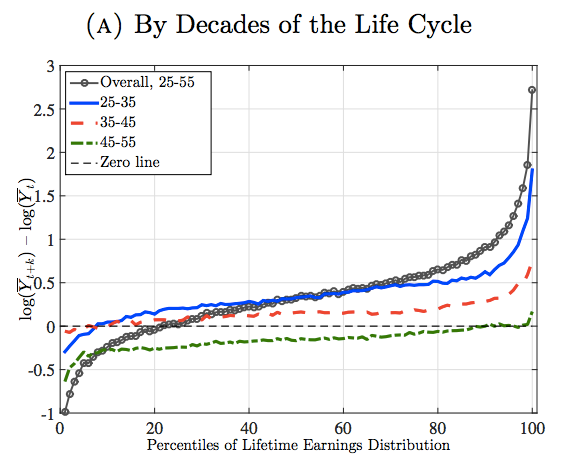

For the visually inclined, here are those trends graphed. On the x-axis, you have where each man falls on the income distribution based on his lifetime earnings. On the y-axis, you have earnings increases during each decade of life. Again, note that most of the growth happens during the first 10 years in the working world (the blue line).

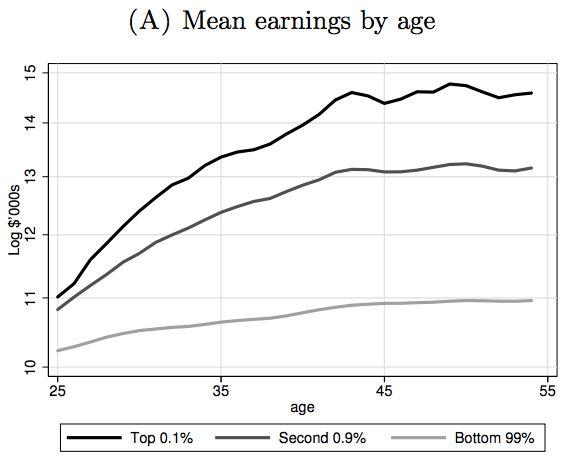

Here’s another, perhaps simpler, way of looking at the trend, from a related paper released earlier this year based on the same dataset. For the super-rich (0.1 percent), rich (1 percent), and the rest (99 percent), income basically plateaus after the early-40s.

Of course, we’re only talking about averages. There are people out there who have late-age renaissances and start earning like never before. But most of us are not Louis C.K. We set up our careers by our mid-30s, either by working up through the ranks of a company or going to school to position ourselves for a pay bump once we have our fancy degree. By middle age, we pretty much are what we are, professionally. Or, as Schopenhauer supposedly said: “The first forty years of life give us the text; the next thirty supply the commentary.”

Via the Washington Post’s Danielle Paquette

Correction, March 3, 2015: A credit on a chart in this post originally misspelled the last name of Federal Reserve researcher Fatih Karahan. The credit also misidentified one of the authors of the 2015 staff report; it was Serdar Ozkan, not Greg Kaplan.