/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/45771924/GettyImages_176413751.0.0.jpg)

The fight over the Keystone XL pipeline has been raging for so long it seems almost routine at this point. This month, Republicans in Congress passed a bill to approve the pipeline once and for all. On Tuesday, President Obama vetoed it, saying he still needed more time to decide. And on and on it goes...

So this is a good moment to step back and appreciate just how truly and deeply unexpected it is that we're even having this fight in the first place.

That is, it's genuinely surprising that the Obama administration has now spent years and years agonizing over a single pipeline. It's surprising that this one project has become such a political flashpoint that Senate Republicans decided to spend the first two months of their newly-won majority on a Keystone bill they knew would be vetoed.

Indeed, the fact that Keystone XL is now one of the biggest stories in American politics tells us a lot about how the politics of energy and climate have shifted radically since 2008. It's the story of how President Obama became the locus of action on global warming, of how the White House developed an uneasy relationship with North America's newfound oil boom, and of how greens have had to lower their expectations for what Washington can do to address climate change.

Keystone XL only became a key issue after more ambitious climate efforts failed

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2457240/9848099276_6e31084889_k.0.jpg)

An anti-Keystone protest in Madison, Wisconsin. (Light Brigading/Flickr)

Few people could have seen this fight coming when Obama first took office. Back in 2008, when TransCanada first applied for a permit to expand its existing Keystone oil pipeline system, virtually no one cared.

The company's logic seemed banal enough. With global oil prices rising, more and more companies were mining crude from the oil sands of Alberta. But those companies needed a way to transport the crude to refineries that could turn it into gasoline and usable fuel. Pipelines were an obvious option.

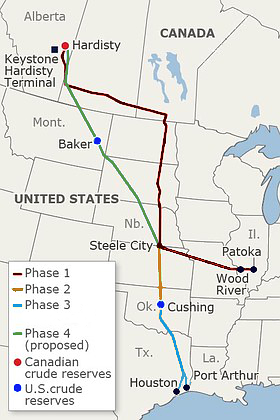

What's more, TransCanada had already been building a network of pipelines from Canada down to Texas, starting in 2005. The new Keystone XL system would simply expand that existing network, bringing 830,000 barrels of crude per day from Alberta down to Nebraska, where it would go on to refineries in the Gulf Coast. The company figured approval would be a slam-dunk.

What TransCanada didn't count on was that the politics of global warming would change rapidly in just a few years. Back in 2008, the biggest green groups were still mostly focused on persuading Congress to pass a sweeping bill to cut US greenhouse-gas emissions. But then the Senate killed the big cap-and-trade bill in 2010, and, soon after, Republicans retook the House — with no intention of addressing climate change. Environmentalists were utterly defeated, and started casting about for a more winnable fight.

That's how Keystone became a potent issue. Around 2011, environmentalists like Bill McKibben began pointing out that oil-sands crude is worse for global warming than regular crude because of all the extra energy it takes to extract. NASA scientist James Hansen warned that burning every last drop of oil in Canada's vast oil sands would mean "game over" for climate change.

And greens didn't have to rely on Congress to do something about this. Because Keystone XL would cross international borders, the State Department had to approve it first. That meant Obama had final say. So the pipeline became a rallying point for greens — a clear goal they could achieve through pressure on a president who had vowed to tackle global warming.

True, blocking Keystone XL wouldn't do nearly as much to curb greenhouse-gas emissions as broad climate legislation would have. But it was also far more straightforward. No longer did climate activists have to wait around for NGOs in Washington to lobby congressional committees over complicated, loophole-ridden bills. They could take to the streets with a simple demand — and engage a fight where it was clear what victory would entail.

The focus on Keystone also jibed with an evolution in how scientists and greens were thinking about global warming. Increasingly, they were noting that the world had delayed addressing emissions for so long that we were on pace to blow past the long-standing 2°C "limit" for global warming. The only way to stay below that threshold would be to leave much of our vast current reserves of oil, gas, and coal in the ground, unburned. As Hansen had noted, fully exploiting Alberta's oil sands would make that task much, much harder.

And so, increasingly, environmentalists were focused not just on policies to reduce emissions (say, by bolstering solar and wind power or by taxing carbon), but also on efforts to curtail fossil-fuel production. They wanted to stop companies from digging up oil, gas, and coal in the first place.

Obama's uneasy relationship with the oil boom

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3445882/184029546.0.0.0.jpg)

Photo taken August 21, 2013 shows a pumpjack (also known as a Nodding Donkey) near Tioga, North Dakota. (Karen Bleier/AFP/Getty Images)

This new movement put the White House in a bind. Obama has long said that he takes global warming seriously — during the 2008 campaign, he supported a sweeping proposal to cut US greenhouse-gas emissions 80 percent by 2050.

But at the same time, the United States has been trying to claw its way out of a deep recession. And the recent oil boom in North America — which only began in the mid-2000s, and was driven by high global prices and new technologies like fracking and horizontal drilling — has been one of the few economic bright spots.

For much of his presidency, Obama has tried to balance these two concerns by touting an "all-of-the-above" approach to energy. On the one hand, he'd push policies to boost clean energy (the 2009 stimulus bill had $90 billion for things like solar, wind, and electric cars). He'd also support regulations to chip away at America's demand for oil, gas, and coal — like the fuel-economy standards for cars and light trucks, or the EPA's forthcoming rules to crack down on carbon-dioxide emissions from coal plants.

But, at the same time, Obama was also committed to supporting oil and gas production in the US. After all, the fracking boom was helping to lift up the US economy. And, more recently, the glut of oil from North Dakota and Texas has driven prices back down and led to cheap gasoline at the pump. That's been a huge political boon to Obama.

What's more, the administration reasoned, the real climate problem was humanity's demand for fossil fuels. The best way to fight global warming was to curb our use of dirty energy — not to block individual projects that would have a small effect in the grand scheme of things. (Back in 2013, the State Department argued that blocking Keystone XL was mostly futile as a way to tackle climate change. So long as oil demand was high, Alberta's crude would find a way to market, whether by pipeline or train or some other route.)

But environmentalists had long insisted that Obama couldn't have it both ways. He couldn't profess to care about global warming and support more oil and gas drilling. And, with Keystone XL, they found a way to pressure the White House on exactly this point. Either Obama could approve the pipeline or he could deny it. There was no middle ground, no way to fudge.

Unable to choose, the administration dithered on a decision for years. And Republicans soon saw a perfect opportunity to pounce. For them, backing Keystone XL was a no-brainer — the pipeline would create (some) jobs and bolster the flow of oil from a friendly neighbor. (It helps that most elected Republicans aren't terribly concerned with climate change.) What's more, the pipeline was broadly popular with the public. For the GOP, it was a perfect wedge issue, a chance to show that Obama was throttling the economy with red tape.

No matter what happens with Keystone XL, climate politics has changed

So what happens now? It's unclear how the Keystone XL drama will ultimately end. Obama could end up approving the pipeline, reasoning that it would have a small impact on carbon emissions in the global scheme of things. Or he could deny it, reasoning that even small steps to curtail fossil-fuel production are worth it.

But whatever Obama decides, the politics of climate change have shifted considerably since he first took office. Environmentalists are increasingly focused on curtailing fossil-fuel production — not just demand. The push to ban fracking in New York State and the activism to curtail coal exports in the US Northwest all fall under this strategy. As Elana Schor has reported at Politico, green groups and activists are likely to oppose other pipelines throughout the US going forward.

In other words, Keystone XL may just be a single project, but the underlying trends that made it such a high-profile political issue aren't going away.

Further reading: 9 questions about the Keystone XL pipeline debate you were too embarrassed to ask